Welcome To The Baseball Reliquary

Revisiting the 1988 Dodger Champions

Dodger Legacy Panel The Institute for Baseball Studies at Whitter College will host a Dodgers-centric program on Tuesday, November…

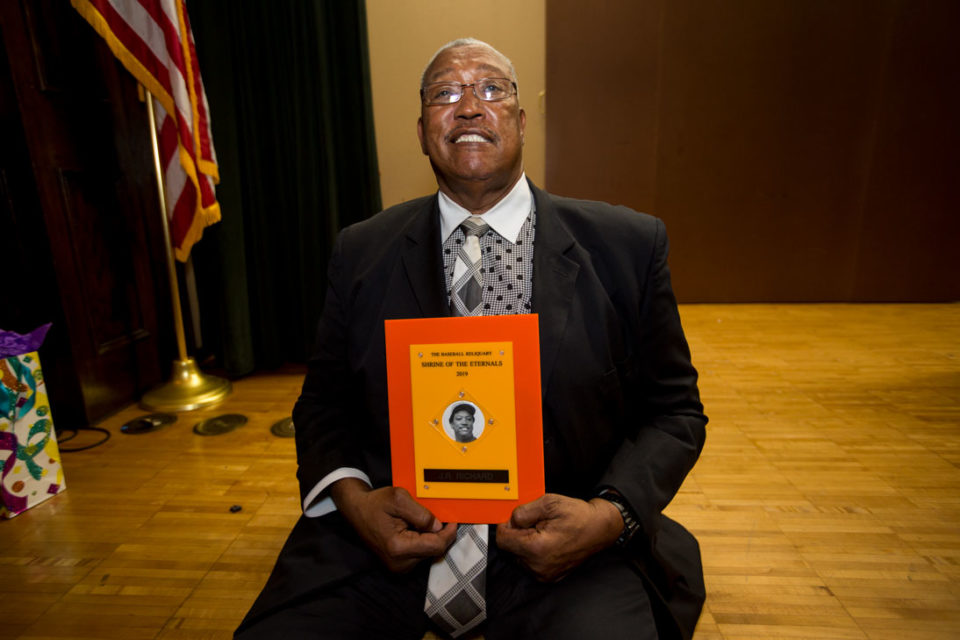

Photos from the Shrine of the Eternals 2019 Induction Day

Photographs by Jesse Saucedo Over 200 baseball fans packed the Pasadena Public Library’s Donald R. Wright Auditorium on Sunday, July…

Photos from “A Swinging Centennial: Jackie Robinson at 100” at Boston Court Pasadena

On Sunday, November 17, 2019, at Boston Court Pasadena, a full house enjoyed a very special event in celebration of…

Video from “A Swinging Centennial: Jackie Robinson at 100”

PART 1 On September 29, 2019, at the Westerbeck Recital Hall on the campus of Pasadena City College, the…

Baseball Reliquary Commissions Artwork in Celebration of Negro Leagues Centennial

In conjunction with the nationwide celebration of the Negro Leagues Centennial, the Baseball Reliquary has commissioned artist Greg Jezewski to…

Video from “A Swinging Centennial: Jackie Robinson at 100” at Boston Court Pasadena

On Sunday, November 17, 2019, at Boston Court Pasadena, a full house enjoyed a very special event in celebration of…

Photos from “A Swinging Centennial: Jackie Robinson at 100” at Robinson Park Recreation Center

Photographs by Michael Fernandez On Sunday, December 15, 2019, at Robinson Park Recreation Center in Pasadena, just blocks from Jackie…

Photos from “Stealin’ Home: A Musical Tribute to Jackie Robinson” at Whittier College

On Sunday, November 10, 2019, at the Whittier College Memorial Chapel, 160 attendees enjoyed a very special event in celebration…

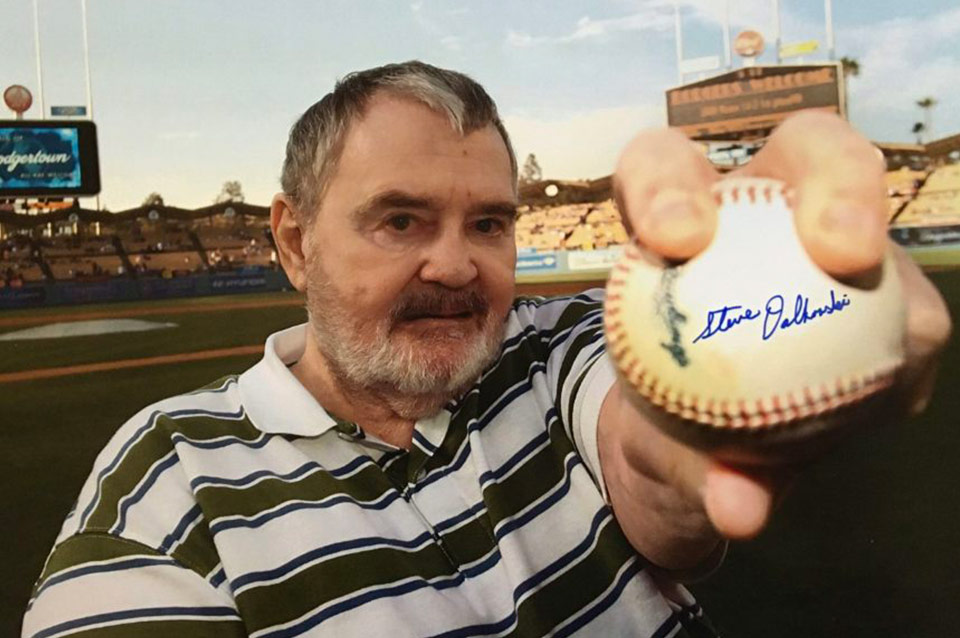

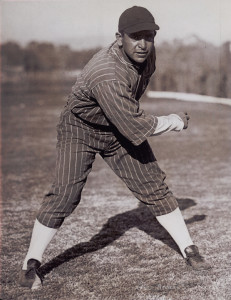

Steve Dalkowski (1939-2020)

The legendary left-handed pitcher and 2009 Shrine of the Eternals inductee, Steve Dalkowski, died on April 19, 2020 at age…

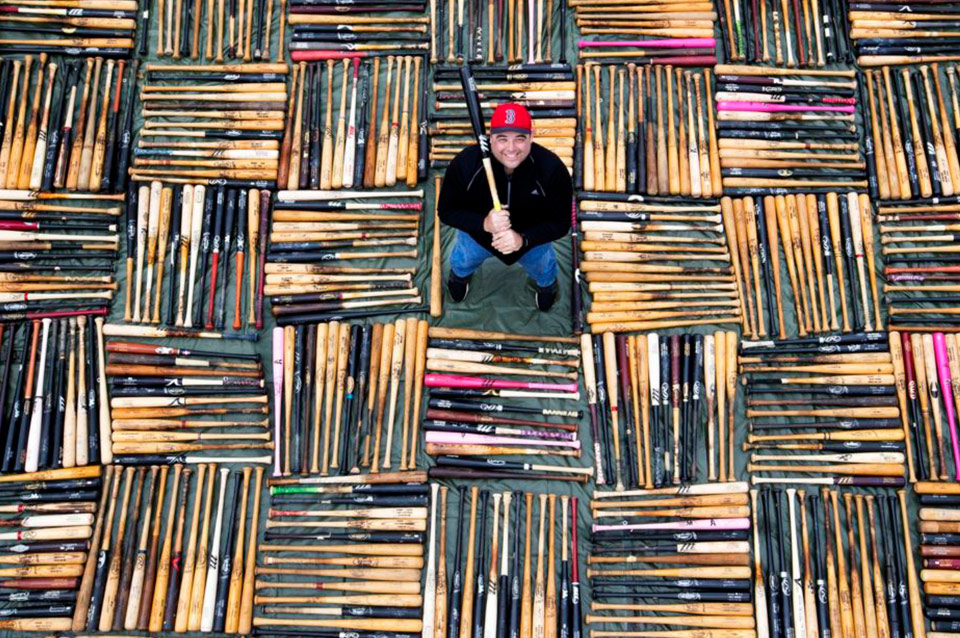

2020 Hilda Award Recipient: Jeff Boujoukos

The Board of Directors of the Baseball Reliquary is pleased to announce that Jeff Boujoukos has been selected as the…

About The Baseball Reliquary

The Baseball Reliquary at Whittier College is an educational organization dedicated to fostering an appreciation of American art and culture through the context of baseball history and to exploring the national pastime’s unparalleled creative possibilities.

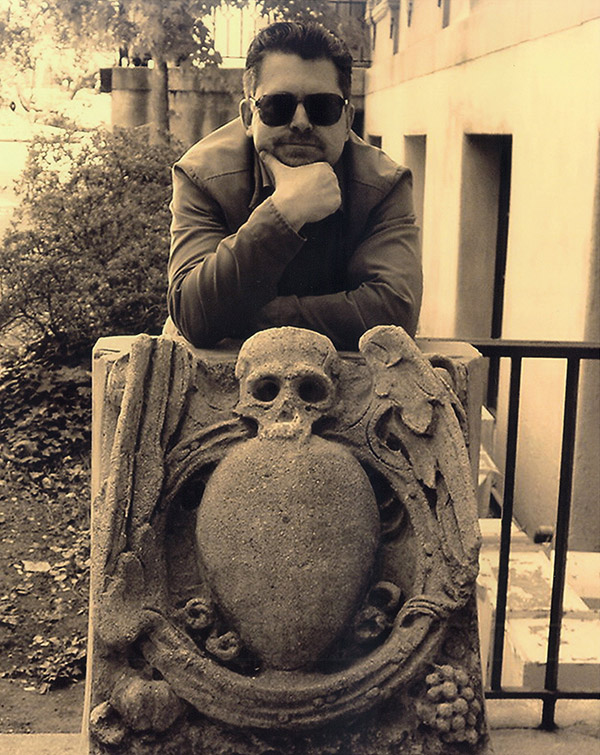

Tribute to

Terry Cannon Founder of the Baseball Reliquary

As a passionate baseball historian, Terry Cannon was an imaginative storyteller who created organizations and opportunities to inform the public about the experiences of forgotten players and unfamiliar teams. In 1996 he conceived and founded The Baseball Reliquary, a non-profit, grassroots educational enterprise with a mission to foster an appreciation of American art, culture, and history through the lens of baseball. Until his death in 2020, Cannon served as the Executive Director of the organization.

In contrast to many baseball ventures, the Baseball Reliquary began as a traveling museum that installed exhibits about baseball history and folklore in public libraries, museums, and university galleries throughout the Greater Los Angeles area. To evoke the evanescent character of the game in the narrative displays, Cannon powerfully utilized pertinent documents, fans’ photographs, peculiar artifacts, and other curious items. Often, the exhibits that he curated and the programs that he sponsored reflected on baseball’s complex relation to racism and sexism. Notable among these presentations were “A Game of Color: The African-American Experience in Baseball” (a two-month exhibit at the San Francisco Public Library) and “Equal to the Game: Women and Baseball” (a public symposium and exhibition at Whittier College).

Under the auspices of the Reliquary, Cannon’s signature exhibit—“Mexican-American Baseball in Los Angeles: From the Barrios to the Big Leagues”—was undertaken in collaboration with the Dean of the Library and two faculty members at California State University, Los Angeles. The extensive display featured oral histories, family photographs, and team documents, and it was so well-received that, after it closed on the CSULA campus, the exhibit circulated through other libraries in Southern California. The project, which had been underwritten with a story-telling grant from the California Council for the Humanities, garnered a prestigious, national award for excellence from the Federation of State Humanities Councils.

When the two-year tour of the project concluded, its archives became housed at the library at California State University, San Bernardino, and Cannon expressed hope then that research on the topic of Mexican-American baseball in Southern California would continue. Although his dream of programmatic affiliation of the project and the Reliquary with a university was not immediately realized, the exhibit spawned the Latino Baseball History Project. Spearheaded by professors Francisco Balderrama and Richard Santillan, the expanding Latino Baseball History Project has sought to document and interpret the significant role that baseball has played in shaping and maintaining Latino communities in the United States, especially in Southern California.

Three years after establishing the Baseball Reliquary, Cannon initiated the organization’s annual celebration of baseball notables in a ceremony known as the “Shrine of the Eternals.” Unlike the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the Reliquary deemphasizes career statistics and record achievements of prospective honorees in favor of recognizing players and others whose impact on baseball was distinct, sometimes subversive, like the influence of pitchers Jim Bouton, Dock Ellis, and Ila Borders. Each year, the members of the Reliquary elect three inductees, whose roster includes a range of players, broadcasters, ballpark personnel, and umpires, as well as former union leader Marvin Miller, “Tommy John” surgeon Dr. Frank Jobe, and “Peanuts” cartoonist Charles Schultz.

In addition to envisioning and coordinating library exhibits and Shrine ceremonies, Cannon also sponsored public programs and commissioned artistic works about baseball, including Greg Jezewski’s triptych “The House that Rube [Foster] Built” and jazz great Bobby Bradford’s “Stealin’ Home,” a musical tribute to Jackie Robinson.

In 2014, Cannon’s vision of aligning the Baseball Reliquary with a college or university was realized when the Reliquary’s library and documents provided the seed for establishing the Institute for Baseball Studies at Whittier College. Now, the art works that Cannon collected and commissioned are on display in the Institute’s library, which also archives other materials related to exhibits and programs that he directed.

A life-long baseball fan and lover of the arts, Cannon was committed to giving voice to ignored and oppressed players and encouragement to underappreciated artists, and he derived great joy in connecting people with each other through the media of baseball and the arts.

(This tribute to Terry Cannon will appear in Mexican-American Baseball in Boyle Heights by Richard Santillan, et al., forthcoming)