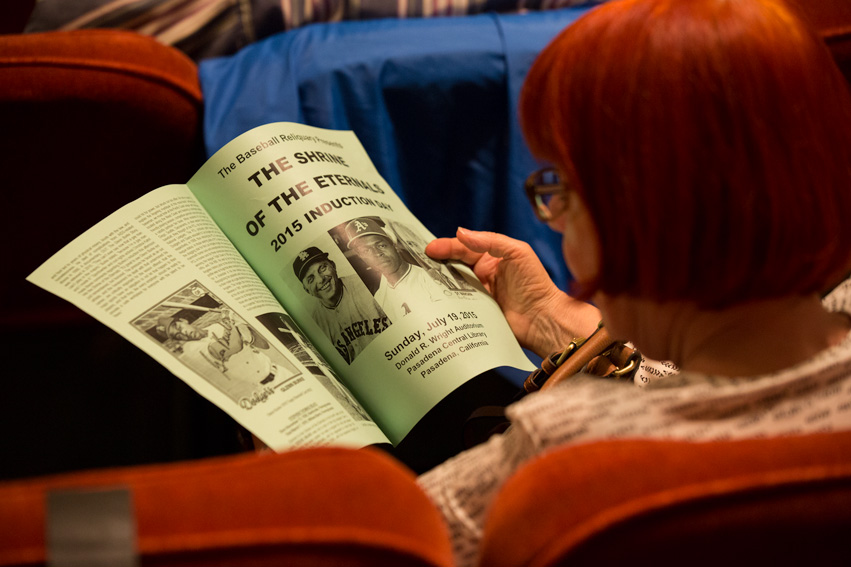

2002 Induction Day – July 28, 2002, Pasadena, California

On Sunday, July 28, 2002, a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 200 people filled the Donald R. Wright Auditorium of the Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, for the 2002 Induction Day ceremony of the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals. The festivities began at 2:00 PM with the traditional bell ringing for the late Hilda Chester, followed by greetings from the Baseball Reliquary’s Executive Director, Terry Cannon, who would serve as the afternoon’s Master of Ceremonies.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was performed on flute by Larry Kaplan, who plays with the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and in the orchestra for The Lion King. Kaplan, who has also been heard on over 40 motion picture soundtracks, followed the National Anthem with a fast-paced and delightful version of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” played on piccolo.

Before the Keynote Address and introduction of the 2002 class of inductees, two awards were presented by the Baseball Reliquary, which, according to Terry Cannon, “represent vital areas of interest to this organization, that is, recognizing the dedication of baseball fans and their importance to the history of the game, and honoring individuals who are engaged in the preservation of baseball history.”

The Hilda Award

The second annual Hilda Award, named in honor of Hilda Chester, was created by the Baseball Reliquary to highlight the importance of fandom in baseball history. Cannon opined that fans have been loyal to professional baseball despite being excluded from “input into rule changes, Hall of Fame elections, divisional realignment, playoff structure, and that new tool of manipulation wielded by major league owners known as contraction. And need we look any further than this summer’s All-Star Game debacle, and the ensuing fan reaction, to make a convincing argument that professional baseball today sorely lacks the qualities of imagination, vision, and the sense of fun that have made it our national pastime.”

Cannon then announced Dr. Seth Hawkins, a retired professor who taught for 35 years in the speech and communications department at Southern Connecticut University, as the recipient of the 2002 Hilda. Affectionately referred to by his friends as Dr. Fan, Hawkins, currently a resident of St. Paul, Minnesota, has pursued a lifelong desire to bear witness to baseball history. He has been present for every 3000th hit recorded in the major leagues since 1959 (there has been a total of 17), in addition to witnessing other baseball milestones such as Henry Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run and Pete Rose’s 4000th career hit, as well as numbers 4191 and 4192, the hits that tied and broke Ty Cobb’s all-time career mark. Hawkins also has seen at least one regular-season game in all 66 stadiums used for major league play from 1950 to the present, including places such as Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, New Jersey; Cashman Field in Las Vegas; Aloha Stadium in Honolulu; the Tokyo Dome in Japan; and the Estadio de Beisbol in Monterrey, Mexico. Cannon added that Hawkins’ extraordinary connection to baseball history includes seeing Hilda Chester clanging her cowbells in the bleachers at Ebbets Field, a stadium that Dr. Fan regularly attended as a youngster growing up in New York in the 1950s.

Cannon then announced Dr. Seth Hawkins, a retired professor who taught for 35 years in the speech and communications department at Southern Connecticut University, as the recipient of the 2002 Hilda. Affectionately referred to by his friends as Dr. Fan, Hawkins, currently a resident of St. Paul, Minnesota, has pursued a lifelong desire to bear witness to baseball history. He has been present for every 3000th hit recorded in the major leagues since 1959 (there has been a total of 17), in addition to witnessing other baseball milestones such as Henry Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run and Pete Rose’s 4000th career hit, as well as numbers 4191 and 4192, the hits that tied and broke Ty Cobb’s all-time career mark. Hawkins also has seen at least one regular-season game in all 66 stadiums used for major league play from 1950 to the present, including places such as Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, New Jersey; Cashman Field in Las Vegas; Aloha Stadium in Honolulu; the Tokyo Dome in Japan; and the Estadio de Beisbol in Monterrey, Mexico. Cannon added that Hawkins’ extraordinary connection to baseball history includes seeing Hilda Chester clanging her cowbells in the bleachers at Ebbets Field, a stadium that Dr. Fan regularly attended as a youngster growing up in New York in the 1950s.

Doctor Hawkins was in attendance to personally accept the Hilda Award, a cowbell encased in Plexiglas with an engraved inscription. He prefaced his largely humorous remarks by saying, “Now you notice that Dr. Fan often refers to himself in the third person. He has the right to do that, established by the famous court case, Rickey Henderson vs. the Baseball Writers Association of America.”

Hawkins remembered his closest call being Tony Gwynn’s 3000th hit in August of 1999: “Now only Dr. Fan would have nightmares for years about Wade Boggs and Tony Gwynn getting their 3000th hits 3000 miles apart on the same night. And people said what are the odds? Very good as it turned out, only one day apart. So after accidentally witnessing Mark McGwire’s 500th home run while chasing Gwynn, Dr. Fan gets to Montreal a mere 11 minutes before the playing of the various national anthems. Knowing that Gwynn was sitting on 2999 and he comes up second in the top of the first inning, the problem was that the people attending the game with Dr. Fan were detained near the border by the language police of the People’s Republic of Quebec for the felony of speaking English in public. But the good news was that we got there in time.”

Hawkins spoke briefly about some of his experiences in Southern California ballparks, saving perhaps his best line for Dodger Stadium, when he remarked, “After a Dodger game, I was observed engaging in suspicious behavior. I stayed until the end of the ninth inning.”

Acknowledging his good fortune at being able to see so much baseball history firsthand, Hawkins added, “This isn’t about Seth Hawkins. It never was, it never will be. It’s about being the ambassador for all fans, for every one of you and the millions of other people who don’t have a conveniently flexible job that lets you off in the summer, who have financial constraints, who have logistical constraints, who can’t get to these events. And once that ball got rolling — pardon the cliché — it’s Dr. Fan’s job to continue to represent all of you. Mr. Ripken eventually sat down; he deserved a rest. But Dr. Fan can’t some fine day in 2014 say, ‘No, I don’t feel like getting on the plane and witnessing Ichiro Suzuki’s 3000th hit’ — you know it’s gonna happen and I even predicted the year. No, he’s got to keep going. That’s fine, that’s not a complaint. The only thing that’s going to stop Dr. Fan is if one of his disgruntled ex-students finally takes some initiative and assassinates him.”

Considering the possibility of such an untimely demise, Hawkins concluded his talk as humorously as he began: “But my pagan friends have assured me that if some disgruntled ex-student assassinates me, it’s not a worry. They say you’ve lived a good life, you’ve made the appropriate sacrifices to the correct gods, and so you will be rewarded after you die and you will go to the Elysian Fields. And I said, NOOOO! I’m not spending eternity in Hoboken, New Jersey! But there’s hope. To paraphrase W.C. Fields, but on an upbeat note instead, after the hospitality that’s been shown to me over the past few days, the thoughtfulness and the great honor of having chosen me for the Hilda Award, I can respectfully decline the Elysian Fields and say, with all sincerity, on the whole I’d rather be in Pasadena.”

The Tony Salin Memorial Award

The afternoon’s second award was created by the Baseball Reliquary to memorialize baseball historian and researcher Tony Salin, who passed away in July of 2001, just a year after he delivered one of the Keynote Addresses at the 2000 Induction Day ceremony of the Shrine of the Eternals. Terry Cannon described Salin, author of the book Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: One Fan’s Search for the Game’s Most Overlooked Players, as “a humorist, prankster par excellence, publicist, activist, and baseball archivist.” The Tony Salin Memorial Award, Cannon noted, “will recognize individuals for their contributions to preserving baseball history and for bringing attention to the stories and legacies of the game’s ‘forgotten heroes’ who are largely unknown to the general public. Individuals from all fields of baseball will be considered, including but not limited to authors, editors, publishers, statisticians, researchers, historians, teachers, curators, archivists, and librarians.”

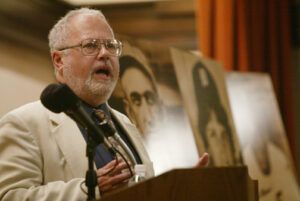

Peter Golenbock, recipient of the Baseball Reliquary’s 2002 Tony Salin Memorial Award and Keynote Speaker at the 2002 Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day

Cannon then acknowledged the presence of two people in the audience who played important roles in Tony Salin’s life: his brother Doug Salin, from San Francisco, and Debbie Caldwell, to whom he dedicated his book Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, from Sacramento. Cannon stated that the recipient of the inaugural Tony Salin Memorial Award was a most appropriate one, the renowned baseball author and historian Peter Golenbock, who has through his numerous books and writings done much to preserve baseball history for future generations. “But on a more personal level,” Cannon remarked, “this gentleman took a young writer named Tony Salin under his wing, made phone calls for him, gave him advice whenever he asked, and provided the support and encouragement without which his book Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes might never have seen the light of day. To say that Peter Golenbock was a mentor to Tony is probably an understatement. In retrospect, he was more of a lifeline for Tony during the five years that they knew one another. And in the sometimes cutthroat and competitive world of baseball writing and publishing, he stands out in the crowd for his generosity and his willingness to share information with, and offer advice to, young authors. And in this respect, Peter Golenbock is doing as much to foster the preservation of baseball history as any established writer today.”

Cannon then invited Golenbock to the podium, while unveiling the Tony Salin Memorial Award, an antiquated baseball encased in Plexiglas with an engraved inscription. Unaware that he was to receive the award, a completely surprised Golenbock spoke briefly about his relationship with Tony Salin: “I get a lot of calls from people who want to publish books, and I try to help them all, with the caveat that I tell each one of them that it’s impossible to get your book published because nobody wants to publish a first-time writer. Tony was one of those who called, and what made him so different was not just the importance of going around the country interviewing old ballplayers, but he had a wonderful way of telling their stories and he was a very interesting person himself. Tony was a guy who drove a cab to the homes of these ballplayers to interview them. It just seemed like a Johnny Carson or David Letterman moment. Here’s Tony Salin, who drives his cab to visit ballplayers and he’s written this book. So it seemed to me that Tony might have a real shot at getting this book published because there was a hook that most of the fellows who want to write books about baseball didn’t have.”

Golenbock referred to the long and arduous process that Salin went through to get his book published, despite many obstacles that he had to overcome: “On the one hand, publishing this book was the greatest achievement in his life, and yet unfortunately you had to know Tony to understand that it was also a very great disappointment to him, because he was convinced that with his publicity abilities he was going to make this thing huge. And, of course, the publishing business doesn’t always work this way.” An emotional Golenbock concluded his remarks by saying he was honored to receive the award.

Keynote Address: Peter Golenbock

Peter Golenbock remained on stage to deliver the 2002 Keynote Address, after a brief introduction by Terry Cannon. His speech covered a wide range of topical issues relating to major league baseball’s current state of affairs. Some of his strongest criticism was leveled in the direction of New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, whom Golenbock referred to as the most malevolent force in baseball: “Born on the Fourth of July, a guy who wraps himself in the flag and who single-handedly threatens to destroy the competitive makeup of our beloved game. Understand something about George Steinbrenner. People say he’s softened. Uh-uh. He has always had the colonialistic mentality of a 19th century robber baron.”

Peter Golenbock

Peter Golenbock delivering Keynote Address at the 2002 Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day

Peter Golenbock delivering Keynote Address at the 2002 Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day

Golenbock briefly talked about how Steinbrenner built his shipping and baseball empires, arguing persuasively that it is Steinbrenner, not Commissioner Bud Selig, who is destroying the game’s competitive balance: “He is the one who is making it impossible for the rest of the league to compete. And what is so notorious about him, like the Enron and WorldCom guys who used their possessions of power to make their millions and who are thumbing their nose at America, Steinbrenner is doing the exact same thing to the other owners of baseball and to the fans here in America.

Golenbock concluded his commentary on Steinbrenner by referring to his possible impact on the ongoing negotiations for a new labor agreement between the owners and the players: “If the players go on strike, it will be I’m sure because Steinbrenner refuses to loosen his grip.”

Following remarks about Bud Selig’s threatened contraction of major league teams and Pete Rose’s ban from baseball (“Rose has been cheated out of his due process”), Golenbock addressed the festivities at hand: “This afternoon, we have come here to honor two men who have brought great joy to our baseball lives and another man who has come to symbolize the unfairness of an autocratic baseball hierarchy: Mark ‘The Bird’ Fidrych, Minnie Minoso, and Shoeless Joe Jackson. We may have no power when it comes to protecting the environment, electing Pete Rose into the Hall of Fame, or stopping the owners and players from committing financial suicide, but here today we have the ability to spread some joy and induct three men we have come to treasure and idolize into the Shrine of the Eternals.”

Shoeless Joe Jackson

Mike Nola, accepting the induction of Shoeless Joe Jackson

In introducing the first of the 2002 inductees, Terry Cannon observed, “Based on the first 12 inductees to the Shrine of the Eternals, I think a good case can be made that the voting membership of the Baseball Reliquary is an enlightened body, and this year’s election of Joe Jackson also exemplifies its compassion. And if I may speak for those members who voted for him, whether or not they felt he was party to the fixing of the 1919 World Series, I believe that they feel that Shoeless Joe Jackson has been punished long enough. And now, some 50 years after his passing, the time has come to lift the ban so that Shoeless Joe can take his place beside the other immortals in the Baseball Hall of Fame. And today, the Baseball Reliquary is indeed proud to have Shoeless Joe Jackson enter its Shrine of the Eternals.”

Accepting the induction of Joe Jackson on behalf of his family and the Shoeless Joe Jackson Society was Mike Nola of Tallahassee, Florida. A computer programmer by trade and Coordinator of Computer Applications for Florida State University, Nola is one of the foremost authorities on Joe Jackson, having spent the last 17 years researching his life. He became actively involved in the movement to exonerate Jackson when he joined the Shoeless Joe Jackson Society in 1990. He developed and currently maintains the Society’s official Web site, which is called the Shoeless Joe Jackson Virtual Hall of Fame (www.blackbetsy.com).

Nola began his acceptance speech with a brief biographical profile of Jackson, stating that his 1915 trade from Cleveland to Chicago would forever change his life. Nola’s most impassioned comments related to Jackson’s implication in the 1919 Black Sox scandal: “I’m here to tell you through all my research, there’s no way Joe Jackson had anything to do with the throwing of any games in the 1919 World Series. He batted .375; he had 12 hits, which was a World Series record; he made five runs; he batted in six. Joe accounted for 11 of the 20 runs that the Sox scored. He had the only home run. He played errorless ball. So those are not the statistics of a man trying to throw any games, in my opinion.

“Now I’m not going to stand up here and tell you that Joe was a saint. I’ve never subscribed to the Saint Joe theory. Joe knew about the fix, he knew that something was going on. But, on the other hand, so did Ray Schalk and Eddie Collins. Charles Comiskey knew about the fix after the first game. He went to the National Commission and tried to tell them what he knew. That is one of my arguments. What makes anyone in their right mind think that if the National Commission didn’t believe Charles Comiskey, one of the most respected men in baseball at the time, that they would have believed the bumpkin from South Carolina had Joe Jackson come forward? They wouldn’t have done it. They would have laughed him out of baseball and the gamblers would have killed him.”

Nola then addressed the issue of the $5000 that Jackson supposedly received for his involvement in the fix: “A lot of people say Joe received $5000. He didn’t receive $5000. The $5000 was left in his room by his teammate Lefty Williams when Joe wasn’t even present. Joe found the money when he came back to his room. He tried to give it back to Comiskey. We’ve got four letters where Joe tries to go to Comiskey over the winter of 1919-1920 to tell what he knows. All he wanted was Comiskey to pay his train fare. Comiskey was a cheapskate, to say the least. He did not pay his train fare because Comiskey was trying to cover up the fix to protect his investment in his players.”

Nola also stressed that, despite press accounts saying that he was a bitter and depressed man after his banishment from baseball, Jackson was “more successful outside of baseball than he was in baseball.” Jackson ran a number of successful businesses in both Savannah, Georgia and Greenville, South Carolina, including a dry cleaning business, a barbecue restaurant, and a liquor store.

Nola mentioned some of the current activities of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Society, including “waiting for Bud Selig to rule on a petition that was filed by Ted Williams in 1998 on behalf of Joe Jackson, asking major league baseball to clear his name. We’ve had two acts of Congress passed; the House and Senate both passed resolutions asking Selig to reinstate Joe Jackson into major league baseball.”

In closing, Nola thanked the members of the Baseball Reliquary for electing Jackson to the Shrine of the Eternals, adding, “It’s a very powerful message and helps our cause to get Joe’s name cleared.”

Mark Fidrych

In his introductory comments about Mark Fidrych, Terry Cannon observed that “in this summer of steroids, contraction, cryonics, and gloom-and-doom predictions of a baseball apocalypse, to recall the innocence and exuberance with which Mark Fidrych played the game and the way he galvanized the city of Detroit and the baseball world in the bicentennial summer of 1976 gives us reason to laugh and feel happy again.”

Cannon also quoted poet Tom Clark, who described the free-spirited pitcher as “ragged, splendid, wild, sticking out of the expectable heraldry of the national pastime like a gigantic puce-and-mauve sore thumb rampant on a field of snow-white jock straps.”

Due to work commitments, Fidrych, who lives on a farm in Northboro, Massachusetts, was unable to attend the ceremony. Cannon noted, however, that “Fidrych is honored to join the Shrine of the Eternals and has asked me to convey his gratitude to the voting membership of the Baseball Reliquary.”

Thom Sharp, accepting the induction of Mark Fidrych

Accepting the induction of Fidrych on his behalf was Los Angeles-based comedian, actor, and lifelong Detroit Tigers fan, Thom Sharp. A Michigan native, Sharp is known to television audiences for his appearances on The Tonight Show and Late Night with David Letterman and as Tim Allen’s older brother on Home Improvement. His ad-lib skills and vocal talents have made him a popular pitchman on radio and TV commercials.

Sharp drew an enormous laugh at the outset by announcing to the audience that although Fidrych was unable to attend, he did have his cap, and proceeded to pull out from behind the podium a Detroit Tigers cap with long curly blond locks of hair dangling from all around its bottom edges. “As a lifelong Tigers fan,” remarked Sharp, “I don’t think there was a greater season, at least for me, than 1976. Not even the ‘68 or ‘84 World Championship seasons. There was nothing like the summer of ‘76. I saw three games at Tiger Stadium that year with Fidrych pitching. And it was like having the Beatles in your lineup. I mean, the place went crazy everytime he did anything. There would be 55,000 people, standing room only, every single game that he pitched. And then the next night, there were, well, three peanut vendors and about six guys in the bleachers.”

Sharp then ran down a list of Fidrych’s accomplishments in that rookie season of 1976. Even though he didn’t make his first major league start until May 15, he went on to win 19 games, lead the American League with 24 complete games and a 2.34 ERA, was the starting pitcher for the junior circuit in the All-Star Game, and garnered Rookie of the Year honors. But, as Sharp noted, Fidrych was also a fascinating character, occasionally bringing to mind Yogi Berra in terms of his unique relationship to the English language: “Bill Veeck once told Ernie Harwell that if someone had tried to stage Fidrych, it would have fallen flat; it would have been artificial and just too contrived. During one of the Bird’s comeback tries, he made it back to the majors and was being interviewed by Harwell, who asked, ‘Hey, Bird, how’s the arm feeling?’”

“’Hey, the arm’s feelin’ pretty good,’ Fidrych replied.

“’Well, really, what does Dr. Livengood [the Tigers’ team physician] have to say about your arm?’ Harwell inquired.

“’Well, he don’t know nothin’ about arms,’ Fidrych answered. ‘He’s a skin doctor. He’s one of them gynecologists.’”

Sharp continued: “Boston Red Sox pitcher and Shrine of the Eternals member Bill Lee said of Fidrych that he was like a little boy thrown into a pile of horse manure. He’s bobbin’ up and down, and they say, how can you be so happy. And he says, there’s gotta be a pony in here somewhere.”

Bringing things into the present, Sharp sarcastically offered, “Actually the Tigers could probably use Fidrych now. If we lose six more games this season, we’re eliminated from next year’s postseason. So it’s not goin’ well.”

“Mark Fidrych had one great, unbelievable, cinderella year,” Sharp concluded. “And I don’t think we should feel too sorry for him that it only lasted a year. In my personal opinion, he had the best season anyone has ever had. He’s had a great life, a lot of great memories, a beautiful wife and daughter, and a strong business. And I’d just like to thank Mark Fidrych for giving me the best season I’ve ever had in baseball. Thank you, Mark, and congratulations.”

Orestes “Minnie” Minoso

Tomas Benitez, introducing Minnie Minoso

The third and final inductee for 2002, Minnie Minoso, was introduced by Tomas Benitez. No stranger to the Shrine of the Eternals (he delivered a Keynote Address in 2000), Benitez is a student of baseball history and has worked as an arts professional for over 20 years. Born and raised in East Los Angeles, California, he is a member and past President of the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; has worked closely with community-based groups in East Los Angeles, including Plaza de la Raza and the Bilingual Foundation of the Arts; and currently serves as director of Self-Help Graphics and Art.

In providing an overview of Minnie Minoso’s career, Benitez offered an historical timeline: “In 1949, young GIs returning victorious were buying homes for $10,000, enjoying the benefits of the GI bill, and were driving De Sotos and Hudsons. There was a new thing they were putting in their new little stucco houses called television. And Mr. Minnie Minoso was playing professional baseball.

“In the ‘50s, it was those big finned convertible Caddies, those ragtops. And there was Sputnik and hula hoops. Baseball was coming west, and James Dean and Milton Berle were popular heroes. And Mr. Minoso was playing professional baseball.

Orestes “Minnie” Minoso

“In the ‘60s, the VW Bug was the number one seller. And television got color: red, blue, yellow, Diahann Carroll and Bill Cosby. The Beatles first came to the United States. And Bob Gibson was making both black and white players turn gray. And Mr. Minoso was playing baseball.

“In the ‘70s, Star Wars was brand new to the screen. Men wore two-inch heels and three-piece suits. Mr. Minoso, in celebration of the Bicentennial, became a United States citizen. And in the summer of Mr. Fidrych, Mr. Minoso became the oldest active professional baseball player to achieve a hit in a major league game. Mr. Minoso was playing baseball.

“In the early ‘80s, Reagan declared the Soviet Union ‘the Evil Empire.’ Raging Bull, the greatest film I’ve ever seen, was being made. And there was something out in L.A. called Fernandomania. Mr. Minoso was playing baseball.

“And in 1993, on June 30, playing for the son of the man who had first signed him, Bill Veeck, Mr. Minoso appeared in a game for the St. Paul Saints of the Northern League and became the first active baseball player over six decades of professional sports, including 40 contiguous years of playing major league professional baseball.”

In further reference to the longevity of Minoso’s career, Benitez added, “There’s another fellow out there in Chicago, a wonderful man named Ernie Banks, who used to be known for his old adage, ‘Let’s play two.’ I think Mr. Minoso should be known for ‘Let’s play on.’”

Benitez concluded his introduction by talking about the recently-played All-Star Game, whose rosters were well represented by Latino ballplayers: “But all these fellows owe a debt of gratitude to the first bonafide Latin superstar of major league baseball, el numero uno, the most popular player in White Sox history, the Cuban Comet, Saturnino Orestes Arrieta Armas Minoso. That sounds like half a team, but it’s just his name. Ladies and gentlemen, it is my humble honor to bring to the stage for your benefit, Number 9, Mr. Minnie Minoso.”

Minoso received a warm ovation and proceeded to offer his heartfelt thanks to the audience in attendance and to the Baseball Reliquary for electing him to the Shrine of the Eternals. Minoso acknowledged the presence of his daughter, son-in-law, and grandchild, who live in San Diego; and Jim Stocchero, his long-time friend who traveled with him from Chicago.

Minoso also noted that Pasadena, California was a very meaningful city for him personally, as it was the first city he trained in with the Chicago White Sox in the spring of 1952. And now, 50 years later, he had returned to Pasadena to accept his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals. Expressing his love for his fans and his country, Minoso concluded by saying, “God bless every one of you and God bless America.”

Induction Day photographs courtesy of Larry Goren