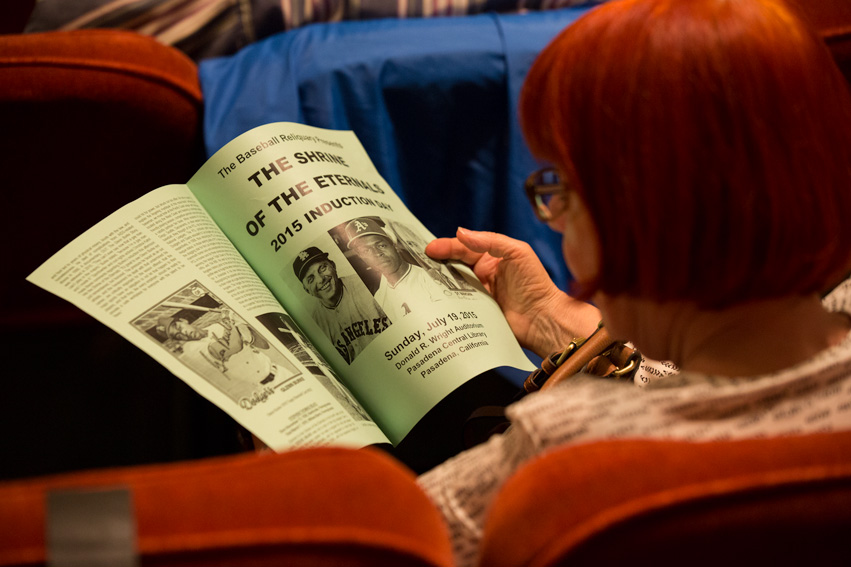

Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day, Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, July 14, 2019

Ralph Carhart accepts the Hilda Award, Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day, July 14, 2019 (photo courtesy of Jesse Saucedo)

It occurred to me, as I was preparing to come out here today, that there is a similarity between the story of Hilda Chester and the Hall Ball. You see, when the Hall Ball was conceived eight years ago I envisioned a day very much like this, only 2755 miles away from here. The intention was to take a picture of the ball with every member of the Hall of Fame, both living and deceased, and then give the ball to the folks at Cooperstown. I love the Hall, and the instant feeling of childhood that washes over me as soon as I walk through its doors. I love the town and the ever-present vibe that exists on its streets, especially when you are there on induction weekend, a time when grown men and women, accompanied by their own children, become little boys and girls again. I wanted to, in my non-athletically-inclined way, make my mark on this great game that we all love.

Ralph Carhart and the Hall Ball with Baseball Reliquary executive director Terry Cannon, Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day, July 14, 2019 (photo courtesy of Jesse Saucedo)

When Hilda Chester was just a little girl known as Hilda Chesler, she also wanted to make her mark on the game. She had something I didn’t have, though. Talent. She could play. She played well enough that the boys who gathered on the open lots of New York City in the first decade of the twentieth century actually let her join them in their pick-up games. She was talented enough to dream of playing professionally, maybe even on an all-woman squad that she would organize and barnstorm around the country. It is possible that in another time, the opportunities provided to her would have been equal to her talent and ambitions. We will never know, because of the sexism that still permeates the game today, largely barring women from becoming professional ballplayers, and serving as a virtually insurmountable obstacle to the dreams of countless little girls.

For myself, I thought my dream ended when I received an email from the Hall of Fame last October, roughly three weeks after I submitted the Hall Ball to their accessions committee. The email was polite and complimentary, if a little pandering. They didn’t want it. Eight years, 44,000 miles traveled (almost enough to circumnavigate the earth twice), and cough-cough dollars later, and the Hall was not interested in the present I had made for them. I reached out to the tiny fan base that I had accumulated over the life of the project and asked them what I should do next. Stage a protest at the Hall? Hurl the ball into Sheepshead Bay? Start watching football? Horrors. Never.

Ralph Carhart with J.R. Richard, Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day, July 14, 2019. Note that J.R. is holding the Hall Ball in his right hand. (Photo courtesy of Jesse Saucedo)

Hilda made a choice when her dream ended. She decided that even though she couldn’t play the game, she was still going to love the game. At first, that was not as easy for her to accomplish as you might have imagined. She was devastatingly poor her whole life. She was forced to place her daughter, Bea, in an orphanage because she could not afford the expense of life as a single mother. Later, when she was a favorite of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the New York Daily News, as well as Milton Berle and Jack Paar, Hilda never revealed anything about the father of Bea in the dozens of interviews she gave. She traveled this life largely alone, her only ever-present companion was baseball. She didn’t start attending games at Ebbets Field regularly until Bea was all grown-up, was in fact, on her way to fulfilling her mother’s dream, when she appeared for both the South Bend Blue Sox and the Rockford Peaches in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, what we now think of as the “League of their Own.” In Brooklyn, Larry MacPhail started offering Ladies Nights and Hilda, who was nearing 40 at this point, took advantage of the ten-cent seats once a week. Within just a few years, this little woman from Brooklyn who, while still younger than I am as I stand before you today, looked like your bubbie, had become the face, the voice and, yes, the cowbell that came to represent the Dodgers, the borough of Brooklyn and the passion of every crank, bug, and fan across the country. Her dream was deferred but her legacy became something that she likely never would have known should she have achieved her original goal and become a bloomer girl. At best, she would have been just another name in the box scores printed in the newspapers of Peoria, and Altoona and Asheville. Today, her name is mentioned in every story about those rare fans who go beyond the normally acceptable level of devotion. People like Emma Amaya and Bart Wilhelm, previous Hilda winners who are here today. They have both made their mark on the game, in their own way. And now each of them has, tucked away somewhere in their homes, a rusted old cowbell, emblazoned with the name of our patron saint.

Hilda Chester with the silver bracelet presented to her by the Brooklyn Dodgers as the best bleacher fan, Ebbets Field, August 7, 1943.

I didn’t throw the Hall Ball in the river. And I certainly didn’t start watching football. Rather, with the help of my friends and loved ones, two of whom, my wife Anna and our beloved Amelia, are here today, I realized that even though the original goal was for the ball to go to Cooperstown, that didn’t mean it had to be the final goal. The Hall of Fame does not have a monopoly on devotion. Perhaps another institution would be interested in displaying it. The first person I contacted was Terry Cannon, here at the Baseball Reliquary. The choice was easy. You see, I know why the Hall didn’t take the ball. The project is weird. Really weird. I mean, who does this? The Hall of Fame is filled with artifacts that remind us of when the heroes of our childhood were strong and powerful. The story of the Hall Ball is the story of what comes after that. It is a story that unifies the still-living, but older, heroes who are no longer the strongest and the fastest, with the ones who have passed and turned to dust. That connection, not soaked in the nostalgia they prefer in Cooperstown, but rather a celebration of this brief ride we all get called life, was a perfect fit for a place that is home to some of the more unusual curiosities from the story of our game. The day that Terry said the Reliquary would be happy to be the home of the ball, I felt like Hilda must have on that day in August, 1943, when the boys got together and bought her a silver bracelet and presented it to her on the sacred grass of Ebbets Field. The Hall Ball had found a home and, in the end, it turns out it was where it was meant to be all along, just like an old woman sitting in the bleachers in Flatbush, ringing her bell all the way into history.

Thank you for this honor.

*****

Ralph Carhart lives in Brooklyn, and is a production manager in the Department of Drama, Theater, and Dance at Queens College. His book, The Hall Ball: One Fan’s Journey to Unite Cooperstown’s Immortals with a Single Baseball, will be published in 2020 by McFarland & Company.