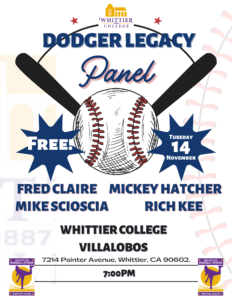

The Institute for Baseball Studies at Whitter College will host a Dodgers-centric program on Tuesday, November 14, at 7:00 p.m. in Villalobos Hall located at 7214 Painter Avenue in Whittier. Featuring an All-Star cast of Fred Claire, Mike Scioscia, Mickey Hatcher, and Rich Kee, the event is free and open to the public.

In distinct ways each of the participants has played a significant role in the history of Major League Baseball. Claire served the Los Angeles Dodgers in various offices for 30 years, rising to the position of the Executive Vice-President and General Manager when the team won the World Series in 1988. Both Scioscia and Hatcher were key members of that team, and later both played leading roles when the California Angels won the World Series in 2002. Kee was a longtime team photographer of the Dodgers, and his book The Dodger Collection was recently released. Along with many Dodger greats from the 1970s and 1980s, the book features Claire, Scioscia, and Hatcher.

Throughout the last decade Claire has made contributions to the Institute for Baseball Studies, and recently he donated 400 books on baseball, more than a dozen framed photographs and reproductions, and 200 of his personal notebooks from his days as a vice-president and general manager. Identified as the “Fred Claire Collection,” the books and journals expand the Institute’s extensive library of Dodgers materials. The acquisition of Claire’s personal notebooks distinguishes the Institute’s resources by making original documents accessible to students and scholars. About the donation, Claire remarked, “I’m very pleased to be able to make these donations to the Institute for Baseball Studies at Whittier College in that it was in Whittier where I started my career in journalism that ultimately led to my joining the Dodgers.” After graduating from San Jose State University in 1957, Claire took his first job as a sports writer at the Whittier Daily News, where his column “The Claire View” became a regular feature. He later served as a sports writer in Pomona and Long Beach before joining the Dodgers in 1969.

Scioscia made his Major League debut with the Dodgers in 1980 and was a member of World Champion teams in 1981 and 1988. Following his playing career, he served as the manager of the Angels from 2000 to 2018. While guiding the Angels to 1650 wins, the most wins for a manager in franchise history, he led the team to the World Series Championship in 2002, its only one i. Twice he was name the Manager of the Year in the American League, and in 2003 he managed the AL All-Star team to a late-inning, come-from-behind victory over the National League.

As a World Series hero for the Dodgers in 1988, Hatcher hit .368, homered twice, and knocked in five runs in the games against Oakland. It was the highlight of his 12-year MLB playing career during which he compiled a 2.7 WAR. After breaking into the Majors with the Dodgers, Hatcher spent four years with the Twins, who released him following the 1986 season. Then he became the first player signed by Claire in his role as General Manager. Joining the Angels when Scioscia took over as manager of the team in 2000, Hatcher served as hitting coach for a dozen years.

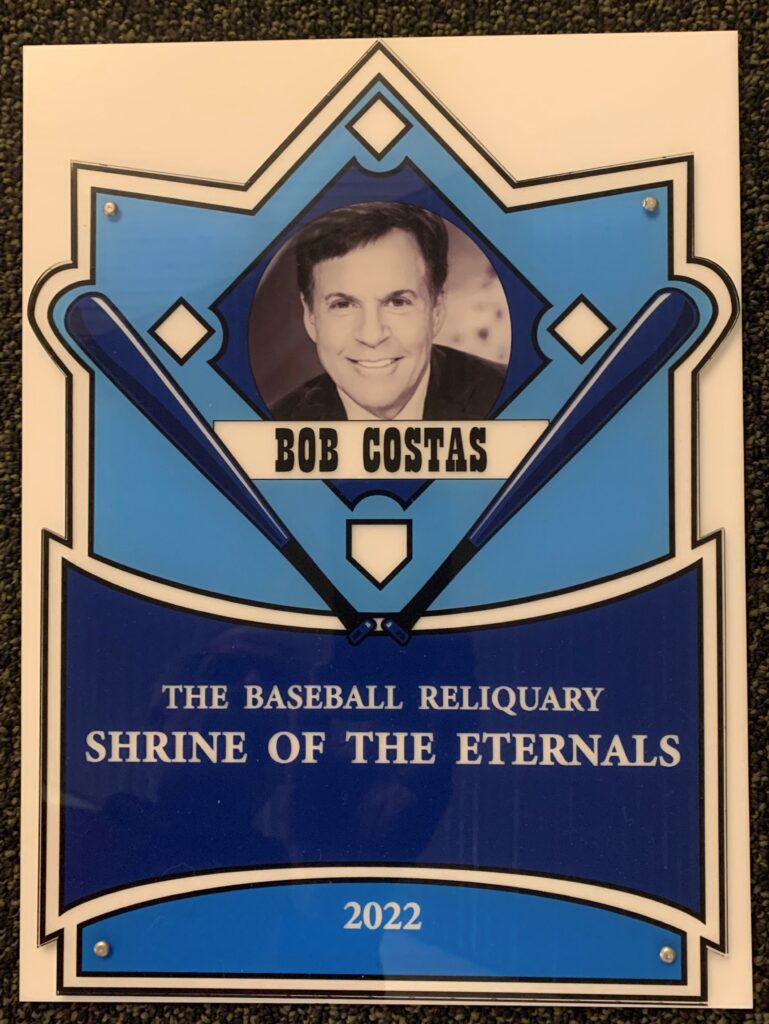

Founded in 2014, the Institute for Baseball Studies at Whittier College is a program and resource center that fosters interdisciplinary studies related to the cultural significance of baseball in American culture. The Institute houses and manages the archives of the Baseball Reliquary.