Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, July 22, 2018

Dan Epstein delivers Keynote Address (photo courtesy of Jesse Saucedo)

Thank you, Terry. Thank you all for coming.

Thank you, Terry. Thank you all for coming.

This is my first Shrine of the Eternals induction event. When I lived in L.A., I always seemed to be out of town whenever this was happening; and now that I live in Chicago, I get to come to one, so that’s pretty beautiful.

Also, I would like to apologize to anyone who expected the author of a book called Big Hair and Plastic Grass to actually have big hair. Summers in Chicago, man . . . I don’t know how Oscar Gamble or Jose Cardenal did it, but I had to cut them off.

It’s a great honor to be here, and what I’d like to talk about today are the concepts of joy, magic, and weirdness, which are things that really have played into my baseball fandom, and I believe these are themes that the Reliquary helps to popularize, in terms of our study of baseball.

The writer Cliff Corcoran once wrote that “the relationship between fathers and sons is baked into baseball’s mythology, as well as reality.” And it’s true, I do owe my original burst of enthusiasm for baseball to my father, a New York Mets fan by way of the Brooklyn Dodgers. One of the first stories about baseball that my father ever told me was about Mickey Owen’s dropped third strike in the 1941 World Series; from that point on, I knew that things don’t always go like you expect them to in baseball.

Rusty Staub

He took me to my very first game — my very first major league game — which was May 30, 1976 at Tiger Stadium. I saw Rusty Staub play right field for the Tigers; my dad was a big Rusty fan from his time with the Mets, but Rusty will always be a Tiger for me, from getting to watch him in those days. I also got to see Billy Martin thrown out of that game before the game even started. It was during the exchange of lineup cards; I had no idea what was going on, and my dad was like, “They had an argument the night before, and this is spilling over.” Later, I realized that Billy was probably really hung over from the night before, and just wanted to get out of the ballpark as quickly as possible.

But for all my father’s contributions to the cause of me becoming a baseball fan, my childhood immersion in the game was really a family affair. My mother grew up a Milwaukee Braves fan; and probably, with some prompting, she can still recite the entire 1957 Braves lineup. She took me to Dodger games during the summers in the Seventies that I spent with her in Los Angeles; she gave me Roger Angell’s Five Seasons for my eleventh birthday, which is a huge book for me, still to this day. And when I was twelve, she inadvertently checked out Joe Pepitone’s autobiography for me from the L.A. Public Library — also a major book for me, but for entirely different reasons.

San Diego Chicken

My sister was a willing partner in my growing baseball obsession. She was quite willing to play catch with me, despite taking probably way too many attempted Tommy John-style sinkers on the chin. And she happily traded baseball card doubles with me; whenever I’d go to the drug store to pick up some new packs, I’d always give her the extra Bucky Dents I had. So, we had a lot of fun with that . . .

I was also lucky, as a baseball-crazed kid, to have grandparents who lived on different sides of the country. My father’s folks lived in both San Diego and Long Island during my childhood, which meant that I got to see Randy Jones and Rollie Fingers pitch for the Padres, and Dock Ellis make one of his last MLB starts as a member of the Mets. It’s also because of them that I got to meet the San Diego Chicken himself, while he was doing a promotion for KGB Radio in front of the San Diego Zoo. I was too shy to approach him — he was handing out postcards to everybody who came by — but my Grandma Rae, like the sweet little Jewish grandmother she was, she sort of coaxed me over. “Go ahead, Dan,” she said. “Shake hands with the Chicken.” Forty-one years later, I hope to do the same later today . . .

Nancy Faust

And then there was my Grandpa Fred, my mom’s dad, who lived in Alabama; so the summers I spent with him there, I got to watch nightly Atlanta Braves broadcasts at a time when most MLB teams were on TV maybe one or two times a week, at most. Grandpa Fred further fed my baseball jones by introducing me to The Sporting News and Jim Bouton’s Ball Four, and paying for my first set of baseball cleats. In the summer of 1977, while schmoozing with his golf pals at the “19th Hole” of his country club, Grandpa Fred handed me a copy of Sports Illustrated to keep me busy. The issue featured Peter Gammons’ story, “Chi, Oh My!,” which celebrated the fact the Cubs and White Sox had somehow both managed to be in first place at the All Star break, and detailed the ecstatic craziness afoot at both Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park. I had never been to Chicago at that point, but Gammons’ article made it seem like the greatest place in the world, at least if you were a baseball fan. Little did I know that, less than three years later, I would be sitting in a box seat at Comiskey, enjoying my first ballgame as a Chicago resident, and listening to Nancy Faust do her stuff on the Hammond Organ . . .

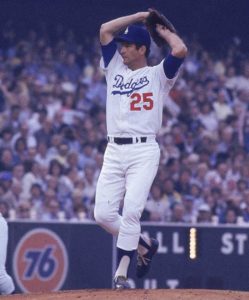

But my favorite Grandpa Fred story actually involves the one time, forty years ago this summer, that he and I were actually able to attend a major league baseball game together. It was July 5, 1978; Tommy John was pitching for the Dodgers against Adrian Devine of the Braves at Chavez Ravine. And on a beautiful, unseasonably cool summer night, Gramps and I took our seats high up in the reserved level along third base line, opened our bags of peanuts, and waited excitedly for the game to begin.

Tommy John

At the time the Braves were absolutely terrible. And with Tommy John on the mound, I figured this would be an easy win for the Dodgers. It certainly started that way; by the end of the third inning, the Dodgers were already up 7-0, thanks to some timely hitting from Ron Cey, Steve Garvey, and Joe Ferguson, and some stellar base-running by Davey Lopes and Billy North. Meanwhile, Tommy John was pitching like . . . Tommy John. Through the first five innings, he’d given up only four singles, hadn’t walked a single batter, and he’d struck out two of them — his thirteen other outs had all come on ground balls, including two infield double-plays. In the bottom of the 5th, Joe Ferguson put the Dodgers up 8-0 with a solo shot off Jamie Easterly. My Grandpa Fred was now entirely out of peanuts, and growing extremely bored by the minute with the slaughter that was unfolding before us. “What do you say we go soon?” he asked me; and while I’ve never been one to want to leave a ballpark before the final out, even I had to admit that this was getting kind of dull. “Okay, Gramps,” I replied. “We can leave whenever you want.”

Well, Gramps had parked his Buick at the farthest reaches of the Dodger Stadium parking lot. It took us a while to get there, and further time to actually find the car; by the time we got into it and switched on the radio, it was already the top of the 7th. The score was 8-3, and Tommy John was no longer pitching; the Braves had finally gotten to him in the top of the 6th, and Tommy Lasorda had pulled him for a young lefty reliever named Lance Rautzhan. “Well, no big deal,” I thought. “No sense wasting your best starter when you’re still up by five, right?”

And indeed, Rautzhan sailed through the 7th and 8th innings, allowing one runner in each inning, but no runs. We were not exactly sailing home, however. Gramps was not from L.A., and when we left the park at a different exit than where we came in, he wound up in Chinatown and had absolutely no idea how to get back to the Fairfax district. He spent the 7th and 8th innings going in circles in and around downtown L.A.; being 12 years old, and not being from L.A. either, I wasn’t really in a position to be of much help. “Where do you think we are, Dan?” he’d occasionally ask. “I don’t know, Gramps,” I’d reply. “But it still looks like Chinatown to me.”

Somewhere along the way, Gramps found Wilshire Boulevard, and knew that if we took that west, we’d get home. Now we were back on track, but so were the Braves: With one out in the top of the ninth, they whacked four straight singles off Rautzhan, cutting the Dodgers’ lead to four runs. With the bases loaded, Lasorda came in and called for the usually reliable Charlie Hough to take Rautzhan’s place, but the knuckleballer didn’t have the goods that night. He immediately walked Gary Matthews to make it 8-5, and then the Braves scored another run when Steve Garvey bobbled a Cito Gaston grounder to first. Hough fanned Bob Horner for the second out, but a young catcher named Dale Murphy followed with a two-run, game-tying single. Out went Hough; in came Terry Forster, who promptly gave up an RBI single to Barry Bonnell, and the Braves had a 9-8 lead. Grandpa Fred just whistled in amazement, while I sat there in stunned silence.

Forster finally stopped the bleeding by getting Pat Rockett to fly out to Vic Davalillo, who then led off the bottom of the 9th against Braves fireman Gene Garber, who was now gunning for a save that had seemed like a complete and utter impossibility just an inning earlier. Garber got the veteran utility man to pop to second, and the Dodgers sent Rick Monday up to pinch hit for Teddy Martinez, who had likewise entered the game as a defensive sub, back when it looked like everything was already in the bag. Right as Grandpa Fred turned off Wilshire and onto La Jolla, Monday flied out to Matthews in right. We were now a block from home. Steve Garvey stepped to the plate, representing the Dodgers’ final hope . . . and right as we pulled into the driveway, Garvey hit a soft fly ball to center that landed in the glove of Rowland Office for the final out. The game was over, and the Braves had come back to win it 9-8. Grandpa Fred turned off the ignition, and I just sat there in the front seat, unsure whether to laugh or cry.

I learned a number of valuable baseball lessons that night, and not just of the Yogi Berra “It ain’t over ‘til it’s over” variety. I learned that just because one team looks significantly better on paper than another, it doesn’t guarantee that the lesser team won’t find a way to win. I learned that late-inning defensive substitutions can sometimes backfire. And I learned that it’s not worth getting too upset about a mid-season loss, no matter how momentarily heartbreaking; come the middle of August, the 1978 Dodgers would seize first place in the NL West, and stay there for the rest of the season, on their way to a second straight appearance in the World Series.

But as I’ve gotten older, my memories of that 1978 game have taught me something else: that sometimes, the experience of the game is more important than the outcome. Certainly, I’ve been to hundreds of ballgames since then, but there are very few that I remember as vividly or fondly as the one game that I got to see in the company of my beloved grandfather. I’ve witnessed walk-off home runs, near no-hitters, acrobatic game-saving catches, triple plays, streakers racing across the outfield . . . but none of those things really match the joy, the magic, and the weirdness of getting lost on the dark and empty streets of downtown Los Angeles with my grandfather, and listening to the game we’d just left turn completely upside-down.

Mark Fidrych

Joy, magic, and weirdness: those are the things that have brought us all here today. We love numbers in baseball; we use them to measure, analyze, and debate the players we see before us, as well as the players of the past. But there are no numbers that can fully quantify the magic of seeing Mark “The Bird” Fidrych pitch in the summer of 1976, or the life-affirming joy that he brought to the fans of Detroit. Numbers cannot fully measure the weirdness of Luis Tiant’s windups, or Bill Lee’s “Leephus pitch,” or Dock Ellis’s “Ellis, D” no-hitter, or the nightmare-inducing image of Dave Parker chugging around the bases in a hockey mask. And likewise, there are no stats with which once can fully gauge just how much Rusty Staub meant to the people of New York City, or any of the other cities he played in, or just how much Nancy Faust means to the sports fans of Chicago, or how just drastically Tommy John’s willingness to bravely undergo an experimental surgery impacted the game as we know it. And that’s why the Baseball Reliquary is so important. Because it’s not about numbers here; it’s about celebrating our memories and experiences, our personal connections to the complex fabric of the game, and the mark the game has left on our equally complex society.

As baseball prepares to lumber into the third decade of the 21st century, I confess that I’m finding significantly less joy, magic, or weirdness in the game than I once did. Maybe I’m put off by the increased emphasis on launch angles and home runs, which has come at the expense of every other offensive tactic. Maybe it’s the replay review system, which has become to baseball what Pro-Tools and digital filters are to music, steamrolling the spontaneous poetry of the moment with our relentless quest for perfection. Maybe it’s the ever-escalating ticket prices, or the new “Mound Visits Remaining” counter, which may be the silliest stat to ever win a permanent spot on the scoreboard.

Tiger Stadium (photo courtesy of Tom Hagerty)

But in dark and troubling times such as these, it becomes more important than ever to connect with what joy, magic, and even weirdness you can find, wherever and however you can. Whatever my misgivings about the current state of our country, and the world, I still feel lucky to be able to watch the latest Javy Baez highlight reel on a near-daily basis. Whenever I enter a ballpark, I still savor that same sense of adrenalized joy I felt upon seeing the bright green grass of Tiger Stadium for the first time. And whenever I get fed up with the present-day version of the game, I can always soothe my soul by immersing myself in its past, in the quirks of its myriad characters, in the rollercoaster rides of its thrilling pennant races, and in its bottomless well of incredible stories. These are the things that the Baseball Reliquary helps keep alive for us, and all of us here today are significantly better off for it.

Long live the Baseball Reliquary.

Long may we all play ball.

And may we somehow find a way to truly become One Nation Under a Groove.

Thank you.

*****

Dan Epstein is an award-winning journalist, historian, and author of Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging ‘70s and Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ’76.