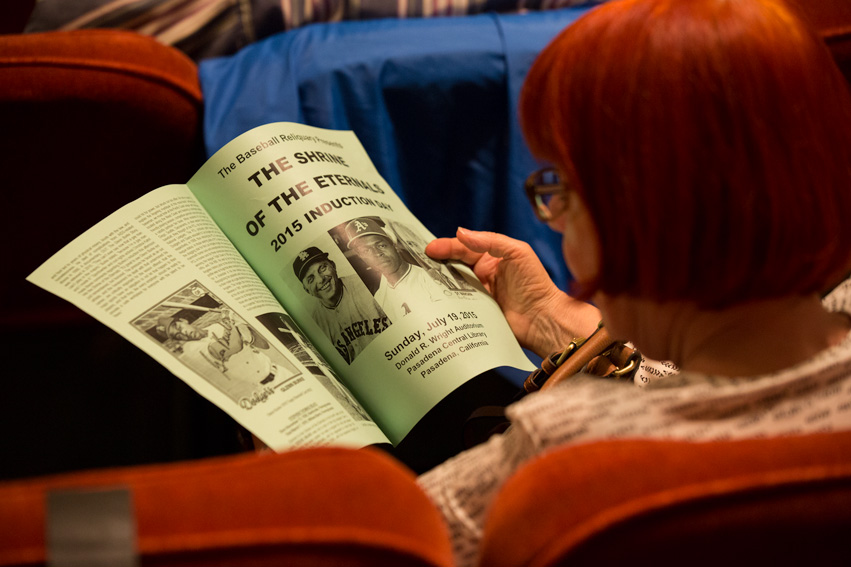

Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, July 16, 2017

Good afternoon. Great to be with you here at the Baseball Reliquary. As Terry Cannon knows, it’s a long way from Detroit to Pasadena. And what a long, strange trip it’s been.

The game of baseball can take you to some of the most unlikely places with the unlikeliest of people. I wouldn’t be here today in the hometown of Jackie Robinson if it weren’t for Ernie Harwell, if it weren’t for Willie Horton, and if it weren’t for Tom Derry and the Navin Field Grounds Crew.

And I wouldn’t be here on the birthday of Shoeless Joe Jackson if it wasn’t for the spirit of Tiger Stadium. It was Shoeless Joe who christened Tiger Stadium over a hundred years ago, back when it was known as Navin Field. In that first game in the top of the first inning, on April 20, 1912, Shoeless Joe scores the first run. Not to be outdone, in the bottom of the first, the Tigers score their first run when Ty Cobb steals home.

For years, that old ballpark at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull was a mecca for many of us in Detroit. But as Cam Perron knows, it wasn’t always a mecca for African-Americans, who were forced to play in their own leagues simply because of the color of their skin.

* * * * *

I grew up on the east side of Detroit. My father, the son of Syrian immigrants from Damascus, taught me the game of baseball. He taught me about Earl Wilson and Gates Brown and Willie Horton. Taught me about Joe Louis and Louis Armstrong. Taught me about America.

We lived in a lower flat on Nottingham Street. On the next street over was an ex-con who somehow made it out of Jackson State Prison and into the Tigers’ starting lineup. His name was Ron LeFlore. Mickey Lolich once lived in that neighborhood. Just a few blocks over was White Boy Rick.

As one of the few Middle Eastern kids in my neighborhood and in my school, I was subjected to my fair share of ridicule. Kids would call me AY-rab, towelhead, camel jockey. You can guess the rest.

As hard as I tried, I never quite fit in. Always felt like a square peg in a round hole. But I feel like I kind of fit in with you here at the Baseball Reliquary.

* * * * *

Despite our best efforts in Detroit, Tiger Stadium is gone, and it’s never coming back. But for anybody who ever set foot in the place, its spirit lives on. It was a uniquely American ballpark in a uniquely American town.

The story of Tiger Stadium, in many ways, is the story of Detroit. It’s the story of America. It’s where immigrants from all over the world came to learn this quintessentially American game. It’s where the Jews came to see Hank Greenberg. Where Italians came to see Rocky Colavito. Where Latinos came to see Ozzie Virgil.

And in the 1960s and ’70s, when the Red Sox were in town, it’s where the Arabs came to see Joe Lahoud. And after the Tigers sign Jake Wood and Willie Horton and Gates Brown, it’s a place where African-Americans can finally come and see one of their own wearing the Old English D.

One of those fans is a Black autoworker at Ford Motor Company who catches the bus to the ballpark all the time to sit in the bleachers and watch Willie Horton and Gates Brown and Earl Wilson. This practically anonymous autoworker — he works in the foundry at the Ford Rouge plant. The same place, at the same time, as a young Berry Gordy.

But he’s not just any autoworker. He’s an old ballplayer who still loves the game. In fact, in his day, he hit the most home runs in Negro League history. His name is Turkey Stearnes.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Norman “Turkey” Stearnes played just a few miles away at a place called Hamtramck Stadium. This was the home of the Negro National League Detroit Stars. There, Stearnes and his teammates played against the likes of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Cool Papa Bell.

And for the grand opening of Hamtramck Stadium in 1930, they ask this middle-aged white guy from Georgia to catch a train to Detroit so he can be on hand to throw out the first pitch at a Negro League ballpark. And he does. And it’s Ty Cobb.

But Hamtramck Stadium wasn’t just a place for the Negro Leagues. After Jackie Robinson breaks the color line in 1947 and the Detroit Stars fold and the Negro Leagues fade into history, Hamtramck Stadium is used for community baseball. High school games, church leagues, American Legion, and Little League.

And it’s there that a big Polish kid by the name of Art “Pinky” Deras leads the 1959 Hamtramck Little League team to the Little League World Series. And to this day he’s called the Greatest Little Leaguer There Ever Was.

But by the 1990s, Hamtramck Stadium falls into disrepair, and the grandstand is scaled down and fenced off, and it’s covered with graffiti.

But it’s still standing.

* * * * *

Today Hamtramck is a vibrant and complex little town. A small town smack dab in the middle of a big one. Once home to Germans and Poles and African-Americans, Hamtramck continues to evolve. And its changing face is the face of America.

Today there are still Poles and African-Americans in Hamtramck . . . and hipsters of all ages playing their music and making their art and living their lives.

And now there are immigrants from Yemen and Syria and Bangladesh. The mayor of Hamtramck today — she’s Polish. And the majority of the City Council are Muslims.

And right there in the middle of it all . . . is this old Negro League ballpark. One of just five or six left in America.

And it’s still standing.

The kids in Hamtramck today — they play a lot of soccer. They play a lot of cricket. And they play a lot of football. And while baseball might not be America’s pastime anymore, it is still a quintessentially American game.

And so Hamtramck High School still has its own baseball team. Their Coach, Adam Mused, is Yemeni. His players are Yemenis, Bangladeshis, Bosnians, and Poles. One kid is half Mexican, half Arab. Coach Mused calls them “the world team.” I call them America’s Team.

Now until just a few years ago, I didn’t even realize Hamtramck Stadium was still standing. But it is. And until just about a year ago. I didn’t even know this place existed.

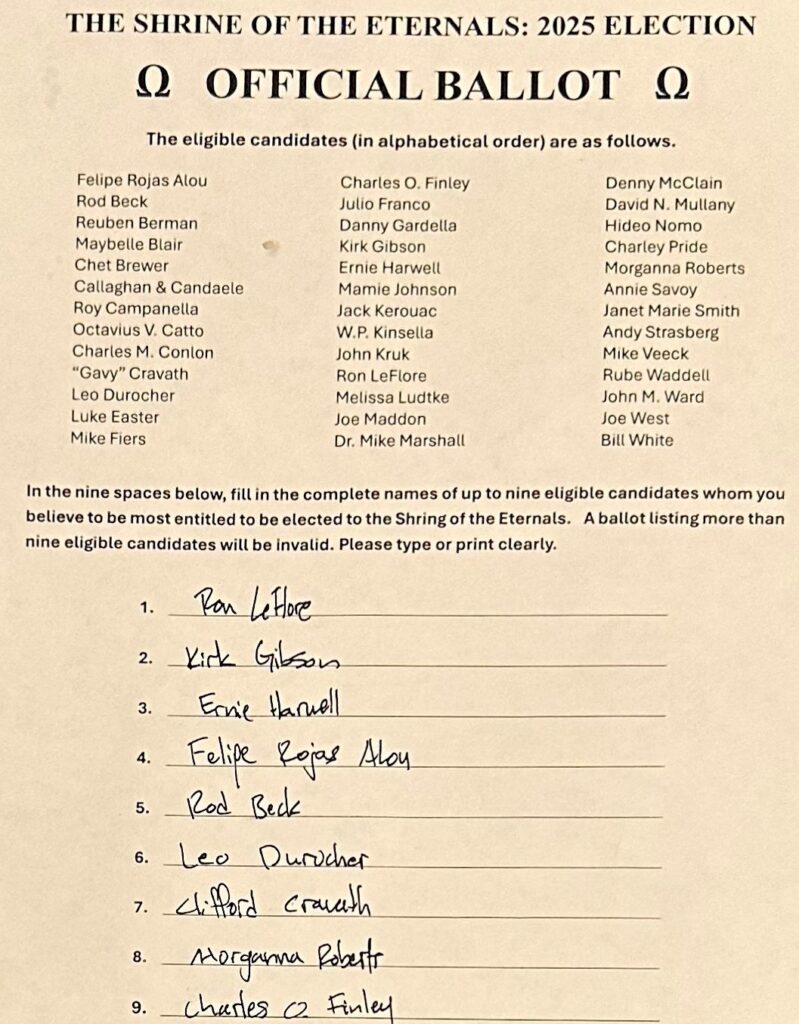

The Baseball Reliquary — a place for guys like Dock Ellis and Bill “Spaceman” Lee . . . and Mark “The Bird” Fidrych. And I’ve started to realize that so many ballplayers who came through Detroit would fit in here. Guys like Turkey Stearnes and Pinky Deras. Dave Rozema and Johnny Wockenfuss. Hank Aguirre and Ron LeFlore.

And while they might never get into Cooperstown, I think maybe there’s even a place here for the longest-serving keystone combination in major-league history, Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker.

I learned about so many of these guys from listening to my father and listening to Ernie Harwell on the radio. And I can trace it all back to the night the Tigers won the pennant in 1968. That night, my parents are sitting in the lower deck of the left-field stands, right behind Willie Horton.

And when Don Wert singles in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth, the place goes bananas. Ernie Harwell says, “Kaline has scored, the fans are streaming on the field, and the Tigers have won their first pennant since 1945. Let’s listen to the bedlam . . . here at Tiger Stadium!”

And from where I’m sitting, it’s all I can do. My mother was five months’ pregnant with me that day. Guess you could say I had an obstructed-view seat. So I can’t see Don Wert’s single. I can’t see Kaline score, and I can’t see the fans go wild.

So I did what Ernie said. I listened to the bedlam there at Tiger Stadium.

And then for the final game at Tiger Stadium in 1999, just like my parents, I find myself sitting in the lower deck of the left-field stands. After the game, all the old Tigers come out in uniform. George Kell and Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker. Bill Freehan and Ron LeFlore and Cecil Fielder.

And then right in front of me, back in left field in his Tigers uniform for the last time, comes Willie Horton. And he’s crying. And Larry Herndon’s crying. And everybody’s crying.

The first one out of the tunnel that night is Mark “The Bird” Fidrych. And I watch as he sprints out to the pitcher’s mound and he kneels down and he pulls out a Ziploc bag and scoops up a handful of dirt to take back home with him to Massachusetts.

And then the lights go down and the crowd thins out, and Ernie Harwell says, “Farewell, Tiger Stadium. We will remember.”

* * * * *

There’s a picture of Turkey Stearnes in his final days in 1979 standing at home plate at Tiger Stadium, where he was never allowed to play because of the color of his skin. Stearnes is just staring out into the outfield, where he sat as a spectator for so many days in the bleachers. And you can see in his eyes the story of the Negro Leagues. It’s the triumph of determination over discrimination, and the triumph of dignity over despair.

I think it all boils down to this: Place matters.

If there’s someplace that matters to you . . . whether it’s an old library or an old house or an old ballpark . . . it’s a place worth fighting for.

And like I said, baseball can take you to the unlikeliest of places with the unlikeliest of people. And so in 2009, when Mark “The Bird” Fidrych dies, I realize I must go to Massachusetts.

Forty-five minutes west of Boston, right outside of Worcester, Mass., is a little town I’d always wanted to visit. But I never got around to it until I got the word that the Bird was gone.

So I hop on a plane and I head out east, and I find myself in this tiny little town where Mark “The Bird” Fidrych was born and raised. And I find the church, and it’s jam-packed and there’s a line outside a mile long. But somehow I manage to get inside, and I stand in the back of the church.

And up there on the altar is a Mark “The Bird” Fidrych jersey, and who should be there to deliver the eulogy — all the way from Detroit — but Willie Horton.

After the funeral, I stumble out into the streets of Northborough, and walk around in awe, and I wander over to Main Street, where I come upon this old abandoned gas station, and I think to myself, “I wonder if this was Pierce’s.”

I remembered that when The Bird signed his first Major League contract, he was a 19-yer-old kid pumping gas at a place called Pierce’s. This is 1974. His father comes up there one day and says, “Markie, you don’t have to work here anymore.”

“And the Bird says, ‘What do you mean?’”

And his dad says, “You’ve just been drafted by the Detroit Tigers.”

And then I look up and I see this guy walking down Main Street, and he’s in a black suit, and it looks like he’s just left the church. Short guy, looks like Robin Williams, and I say, “Excuse me. Was this Pierce’s gas station?”

And he looks at me and says, “Yeah, that was Pierce’s. You not from around here?”

And I say no.

And he sees I’m wearing a sportcoat and he says, “Were you just at the funeral?”

And I said I was.

And then he says, “Are you from Detroit?”

I said I am.

And he says, “My name is Stevie Graham. I’ve known Markie my whole life. We grew up together playin’ Little League together. You wanna buy me a coffee?”

So we walk in to the Dunkin Donuts and I buy him a coffee and he starts telling me what it’s like to grow up with Mark “The Bird” Fidrych. And what it’s like to see him go from your goofy, lovable neighbor to the major leagues and see him standing on TV talking to Bob Uecker on Monday Night Baseball.

Stevie Graham, it turns out, is a hell of a poker player. His buddies call him “The Brain.” And The Brain looks at me and says “You got a car?”

And I say yeah.

And he says, “How’d you like a tour of Northborough?”

So we start driving around Northborough, and he shows me this little house and says, “See that place? That’s where Markie grew up.”

And then we drive around a little more and he shows me this farm, and he doesn’t have to say anything because I know whose farm it is. And I can see off in the distance a big red Mack truck, and I know whose truck it is.

And we drive around a little more, and he says, “There’s one more place I gotta show ya.”

So we drive around town, and we end up at a little ballpark called Memorial Field.

There’s a Little League diamond, and there’s a major-league diamond, and The Brain says, “This is where we grew up playin’ ball. This is where Markie and I learned the game.”

And then The Brain goes and finds the groundskeeper and says, “Tommy, I want you to meet somebody. This is Dave. He came all the way from Detroit for Markie’s funeral.”

And then he says to the groundskeeper, “You got a Ziploc baggie?”

And he says, “Yeah.”

And The Brain tells him, “Go get some dirt from the mound.”

And so I watch this groundskeeper walk out to the mound, get down on his hands and knees, and scoop up a handful of dirt.

And he gives me the bag.

Then I was like, “Shit, Brain, I’ve got something for you.”

He says, “Whaddaya got?”

I’d brought something with me from Detroit. I didn’t know why I brought it or what I was gonna do with it until that very moment. And so I reach in my pocket, and I pull out another bag of dirt, and I give it to Stevie “The Brain” Graham.

And he looks at me and says, “Is that what I think it is?”

I said, “It is.”

And he says, “Is that from Tiger Stadium?”

I said, “It is.”

And he says, “Is that from the fuckin’ pitcher’s mound?!”

And I said, “Aw, I’m sorry, man. That’s from the left-field line. It’s the best I could do!”

So he takes his bag of dirt, I take my bag of dirt, and we go our separate ways.

And then when I get back to Detroit, they tear down what’s left of Tiger Stadium.

It was supposed to be this great historic reuse of an old major-league ballpark, but it wasn’t meant to be. And so they tear it down.

And then Ernie Harwell dies. And they’ve got him laid out at Comerica Park so people can come and pay their last respects.

But I don’t wanna go there. I wanna go to Tiger Stadium. I wanna go to Navin Field. But now it’s this 10-acre vacant lot. And it’s riddled with trash and weeds. But there are people there playing catch in the weeds and remembering Ernie Harwell, and remembering the spirit of Tiger Stadium.

And I meet this guy, Tom Derry, and we come back a few days later and we start picking up the trash and cutting the grass. And the cops start harassing us, but we keep coming back. And soon you can make out the base paths again.

And then the people come. Next thing you know, we’re the Navin Field Grounds Crew and for six years it’s this surreal saga of trying to preserve what’s left of an old ballpark.

But it’s gone now. We couldn’t save Navin Field, but I like to think we kept its spirit alive.

* * * * * *

And now there’s another ballpark that needs restoring. And it’s right there in the middle of Detroit, in this little city called Hamtramck, Michigan.

I’m so pleased to be with you here today in the hometown of Jackie Robinson. It’s been a long, strange trip for a Syrian-American kid from the east side of Detroit.

Now I’m not a scholar like Terry Cannon . . . or a researcher like Dr. Santillan or Dr. Revel . . . or these guys in Detroit, Rod Nelson and Gary Gillette, but as far as I can tell, in the history of the game, there’ve only been two major-league players of Middle Eastern descent.

And there hasn’t been one in 30 years. Not since Sammy Khalifa played shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

So that got me thinking . . . while I’m proud to be here with you at the Baseball Reliquary, I think I’ll be even more proud and more pleased when I look out between the lines of a major-league diamond . . . and see a Middle Eastern face in baseball again.

There’s a kid out there somewhere, just waiting to be discovered. Maybe he’s Yemeni like Adam Mused. Maybe he’s Lebanese like Joe Lahoud. Maybe he’s even Muslim . . . like Sammy Khalifa.

And maybe — just maybe — he’s from Hamtramck, Michigan.

Thank you.

Dave Mesrey is a Detroit-based historian, writer, and preservationist, and a founding member of the Navin Field Grounds Crew.