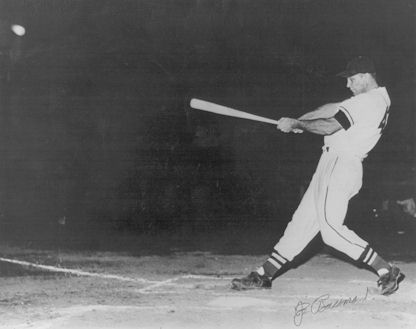

Joe Bauman blasting one of his record-setting 72 home runs in 1954.

(Photo courtesy of the Historical Society for Southeast New Mexico)

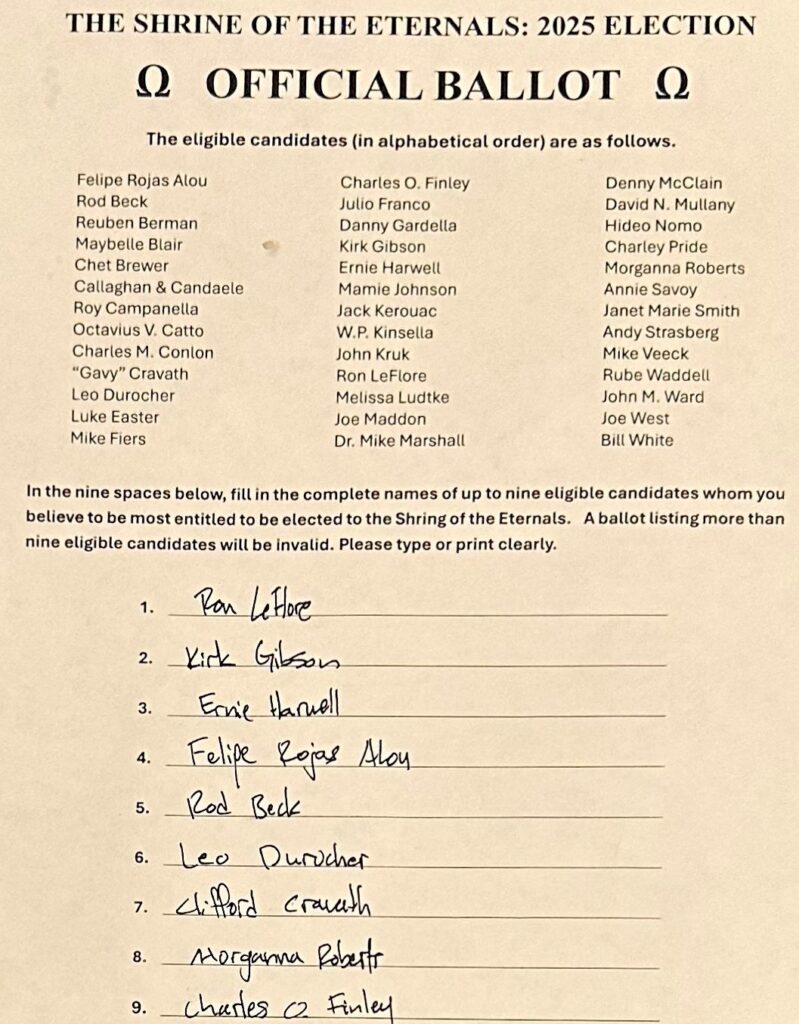

Of the many thousands who have played professional baseball down through the years, only three men have hit 70 or more home runs in one season: Mark McGwire with 70 in 1998, Joe Bauman with 72 in 1954, and Barry Bonds with 73 in 2001. While McGwire and Bonds were among the game’s most celebrated and controversial superstars, Bauman lived in relative obscurity in Roswell, New Mexico until his death in 2005. On September 5, 1954, Bauman, the slugging first baseman for the Roswell Rockets of the Class-C Longhorn League, shattered professional baseball’s single-season home run record by crushing his 70th round-tripper, and in so doing etched his name in stone as a true baseball immortal. In March of 2000, the late San Francisco-based author and historian Tony Salin came into possession of what is believed to be the record-setting ball and, shortly thereafter, donated it to the Baseball Reliquary. The story of the ball is told in Salin’s words:

“I traveled around the country in the spring of 2000 promoting my book, Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, which includes a chapter on Joe Bauman. In March I was in Roswell, New Mexico for a book signing, which was highlighted by a visit by Bauman. That night I was wound up and couldn’t sleep so I drove to the local Denny’s. Roswell is known as a place where strange things happen, and the story I heard that night at Denny’s fit into that category.

“I was sitting at the counter eating a Caesar salad and drinking a Coke and casually mentioned to the guy sitting two stools to my right that I was probably the only visitor in town who came because of baseball, not because of the supposed alien landing. The guy, a fiftyish, bald-on-top gentleman with an excess of character lines and somewhat fuzzy ears, was silent for a second when I made my remark. Then he put down his soup spoon and told me about his father, an industrialist from Chicago named Hans, who had caught Bauman’s 70th home run ball.

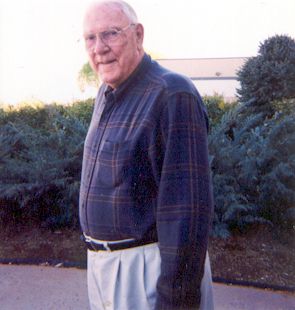

Joe Bauman as photographed by Tony Salin, March 2000.

“The story went something like this. Hans grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he was close to his mother but saw little of his father. The father ran a small machine shop and every once in a while, after work, if Hans did something that pleased him, he’d remark in his native German, ‘Gut, Hans. Das ist gut.’ The phrase stuck in Hans’ head, he thought about it often, and over time he thought of the phrase as, ‘Good hands.’ Hans wasn’t much of a baseball player as a youngster — he couldn’t hit, but he could catch the ball as well as anyone. It became a source of pride with him to be able to catch a ball barehanded as well as, if not better than, his gloved schoolmates. When he attended minor league games in St. Paul, he developed a reputation as the best foul-ball catcher in the stands.

“In 1933, when Hans was in his early teens, Joe Hauser of the nearby Minneapolis Millers was on a home run tear and astonished the baseball world by hitting 69 home runs, which obliterated the single-season home run record he himself had set three years earlier. Many of those home runs were hit in St. Paul, and Hans caught a few of the balls. But he didn’t catch the record-setting home run ball, and that always galled him. According to the story told me by Hans’ son at Denny’s that night, he felt his father perhaps had equated catching home runs with gaining his father’s love. He was obsessed with catching the record-setting home run ball. But it didn’t happen.

“Then in 1954, Hans, now in his early thirties and a successful businessman, dropped everything and headed for the Southwest, where Joe Bauman was making headlines with his quest to break the record set by Hauser in 1933 and tied by Bob Crues in 1948. The ballparks in Big Spring, Texas and Artesia, New Mexico, where Bauman assaulted the record, were filled with local fans and a conspicuous, grim-faced outsider from the north.

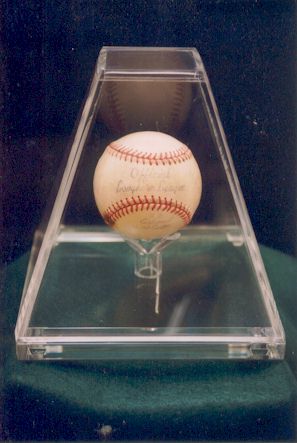

Joe Bauman’s 70th home run ball, now in the collection of the Baseball Reliquary.

“As luck would have it, or perhaps I should say skill, Hans caught the historic 70th home run ball. Even though many in his proximity used gloves, he was able to accomplish the feat barehanded. ‘Good Hands,’ as he was known by close friends and members of his family, had done what he had set out to do. After the game he was surrounded by members of the media and interviewed at length. According to Hans’ son, his father was finally at peace. He left the ballpark and drove back to Chicago.

“But somehow Hans had missed the fact that the Roswell Rockets and Artesia Numexers were scheduled to play two games that day. When Hans later learned that Bauman hit two additional home runs during the second game of the season-ending doubleheader, he was upset beyond words and vowed that he would never again attend a baseball game of any kind. Even though it was the ball that broke the longtime record, it wasn’t the 72nd home run, which Hans considered the one that mattered, and he treated the ball shabbily, kicking it around the house and letting his children play with it.

“Hans’ son told me that his father had recently passed away. The son, whose name was Robert, explained that he was in Roswell to visit the town where his father had been in 1954. He then showed me the ball, which he had brought with him. He explained that he wasn’t a baseball fan and since I was, he gave it to me.

“Whether or not it is the actual ball hit by Bauman in 1954, I don’t know. Robert could have been a local pulling my leg. But the ball is stamped with the official Longhorn League seal, and there can’t be many of those balls left, considering that the league disbanded after the 1955 season. Any way you look at it, the ball is a rare link to a fabled league where one of baseball’s most magical records was set.”