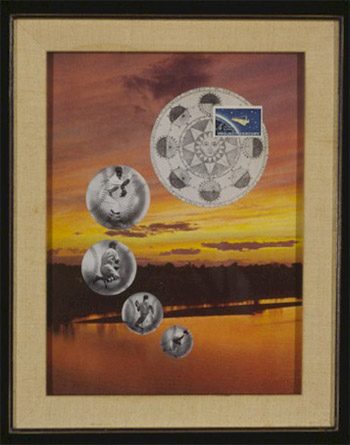

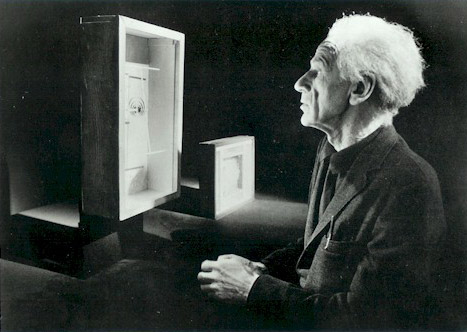

In an exhibition catalog, curator Walter Hopps wrote, “Imagine making beautiful and important art without drawing or painting or sculpting in any of the obvious classical ways. Miraculously, and even magically, the self-taught American artist, Joseph Cornell, achieved this with his intimate box constructions and collages.” In 2000, the Baseball Reliquary announced the acquisition of a photo collage believed to have been executed by Joseph Cornell (1903-1972). This previously unknown collage, with dimensions of 10-1/2” high by 8” wide, surfaced in the fall of 1998 and is purported to be the only work in Cornell’s oeuvre which incorporates images from the national pastime.

Typical of much of Cornell’s artwork (and a circumstance that has frustrated art historians over the years), the collage is not dated or signed. Research, however, indicates the work is from approximately 1962, as it is similar in construction and technique to many of the collages emanating from Cornell’s studio at that time. Cornell introduced often startling subject matter into the collages of this period, including the first openly erotic images of his career and, with this discovery, the first use of baseball as a thematic element.

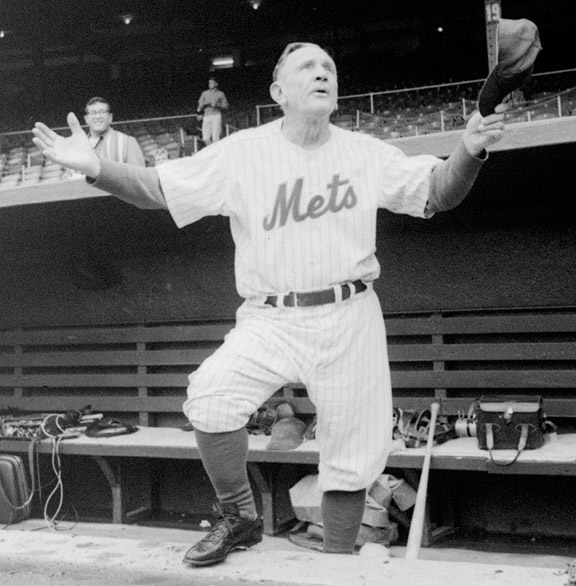

The framed and untitled collage (which, for cataloging purposes, will be called U.S. Man in Space) posits four baseball players, each encapsulated inside their own baseball, traveling through space in the direction of an ancient sun calendar and a four-cent postage stamp commemorating Project Mercury, the pioneering series of manned suborbital and orbital flights. With their spherical shapes and solitary passengers, the baseballs become an amusing metaphor for the historic Mercury capsules. These baseball images are placed against the backdrop of a vibrant sunset taken from the pages of Arizona Highways, a popular source of material for Cornell’s collages at the time. In light of this work’s whimsical nature, art historians have speculated that U.S. Man in Space might well have been inspired by the zany play of the New York Metropolitans. Cornell, after all, lived his entire life in Flushing, New York, and in their first season as an expansion team in 1962, the woeful Mets set a modern futility record by finishing 40-120, inspiring Casey Stengel’s frequent lament, “Can’t anybody here play this game?” On another level, Cornell’s montage elicits a comparison between America’s patriotic allegiance to baseball and the nationalistic fervor with which it embraced the “space race.”

Cornell devotee Keith Ullrich is credited with unearthing U.S. Man in Space, and the process of identifying and acquiring it for the Baseball Reliquary took nearly fifteen months. Ullrich believes that it escaped tracking by Cornell’s estate and art historians because it was one of many different works frequently lent to friends and acquaintances by the artist. In his desire to communicate with young people, Cornell, a lifelong bachelor, often let children in his Flushing neighborhood take boxes and collages home with them. U.S. Man in Space, based on Ullrich’s research, was apparently loaned to a girl and her younger brother who often rode their bicycles by Cornell’s home at 3708 Utopia Parkway. The children’s family moved from the neighborhood shortly thereafter, and the collage was never returned.

Cornell was, in fact, almost compulsively focused on children, to the point of presenting, in 1972, what was probably the first avant-garde art exhibition in New York for children only. At the Cooper Union gallery, Cornell displayed 26 boxes and collages at child’s-eye level, no more than three feet off the ground, and at the opening reception, children dined not on champagne and caviar but on cherry soda and brownies.