July 20, 2003, Pasadena, California

On Sunday, July 20, 2003, a capacity crowd of nearly 200 people filled the Donald R. Wright Auditorium of the Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, for the 2003 Induction Day ceremony of the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals. The festivities began at 2:00 PM with the traditional bell ringing for the late Hilda Chester. The afternoon’s Master of Ceremonies, Terry Cannon, also Executive Director of the Baseball Reliquary, announced that Hilda was perhaps the most famous fan in baseball history, a denizen of the Ebbets Field bleachers in Brooklyn for more than 30 years: “One day, while passing a junk shop near her home, Hilda spotted a cowbell for sale in the window. Price: 10 cents. From that moment on, a mighty percussionist was unleashed in the Ebbets Field bleachers: Cowbell Hilda.”

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was performed on violin by veteran comedian and Pittsburgh Pirates fan Hugh Fink. Fink’s version was inspired by Jimi Hendrix’ legendary rendition of the National Anthem at Woodstock in 1969.

Before the 2003 Keynote Address and introduction of the 2003 class of inductees, two annual awards were presented by the Baseball Reliquary.

The Hilda Award

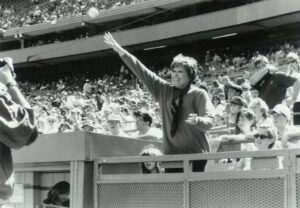

Ruth Roberts, the 2003 Hilda Award recipient, throws out the ceremonial first ball at Shea Stadium on September 15, 1996 at “Meet the Mets — Ruth Roberts Day”

The Hilda Award, named in honor of Hilda Chester, was established in 2001 to recognize distinguished service to the game by a baseball fan. The recipient of the third annual Hilda was lifelong New York baseball fan Ruth Roberts. Roberts has expressed her love of the game through writing music and lyrics for some of the liveliest baseball anthems of the last half century. Along with her frequent collaborator, Bill Katz, Roberts wrote the 1956 song, “I Love Mickey,” a celebration of Mickey Mantle which was recorded by Teresa Brewer. In 1960, she penned “It’s a Beautiful Day for a Ball Game,” the longtime radio theme of the Los Angeles Dodgers. And finally in 1963 came “Meet the Mets,” which was introduced to the public in March of that year and has been played before every Mets home game for the last 40 years. “The song is such a staple among generations of New York baseball enthusiasts,” remarked Cannon, “that some diehard Mets fans have requested that, upon their death, ‘Meet the Mets’ be sung at their funeral before their casket is closed.”

Currently a resident of Port Chester, New York, Ruth Roberts was unable to attend the ceremony due to recent eye surgery. Accepting the Hilda (a cowbell encased in Plexiglas with an engraved inscription) on Roberts’ behalf was her son, Michael Piller, who lives in Los Angeles. Piller offered several anecdotes about his mother’s love of baseball and music. Of “Meet the Mets,” Piller noted: “I am a television writer and producer, and I was at a major network recently pitching my latest project. I was wearing my Mets cap from the World Series with the Yankees. The head of the network asked me if I went to that World Series. And I said, well, yes, my mother got tickets because she wrote the Mets theme song. And his eyes lit up and in front of his entire staff, he sang the entire song word-for-word. I realized then, and wrote to my mother right after that meeting, that what she had really written was a city anthem. She had encapsulated in two minutes the entire experience and memories of the history of a baseball team. The shared experiences of our youth, of our memories and thrills, are bound together by that song. They still play it today before every game in New York, and everywhere I go I now make sure to let them know my mom wrote that song.”

The Tony Salin Memorial Award

The second award was established in 2002 to recognize individuals who are engaged in the preservation of baseball history. The Tony Salin Memorial Award (an antiquated baseball encased in Plexiglas with an engraved inscription) is named in honor of author, humorist, baseball archivist, and prankster par excellence, Tony Salin, who passed away in July 2001 at the age of 49. Cannon stated that the award “was established to memorialize Tony’s commitment to preserving baseball history and to salute and encourage those who continue Tony’s journey in his absence.”

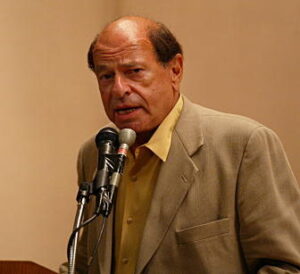

After introducing Tony Salin’s brother, Doug, who was in attendance from his home in San Francisco, Cannon announced that the 2003 Salin Award recipient was David Nemec. A San Francisco resident, Nemec has authored nine novels and 25 books on baseball history and memorabilia. Among his baseball titles are The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball, a definitive work on the early years of the national pastime, which received The Sporting News Research Award; The Rules of Baseball: An Anecdotal Look at the Rules of Baseball and How They Came to Be; The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association — Baseball’s Renegade Major League; and The Great Book of Baseball Knowledge.

David Nemec, the 2003 Tony Salin Memorial Award recipient

Like last year’s Salin Award recipient, Peter Golenbock, Nemec was a personal friend of Salin’s and shared some wonderful reminiscences of Tony. “I’m deeply honored to be receiving the Tony Salin Memorial Award,” commented Nemec. “I’m honored in my own behalf, but it’s also a major honor for me to have a part in your commemoration of Tony and his work. The Baseball Reliquary meant a lot to Tony. Like many of us, he wasn’t much for groups or organizations, but this was that special one that captured his heart and soul.”

Nemec spoke of Salin’s unique gifts as an oral historian: “He would employ a kind of charm and touch to get a Pete Gray or a Joe Hauser or a Joe Bauman to hang on the phone with him for hours and talk about not only their baseball experiences but their entire lives in ways that they had probably never done before with anyone outside their immediate families, let alone a writer who began as nothing more to them than a voice on the other end of the phone. The kind of character that Tony possessed, along with the charm and touch, helped him to eventually prevail in his writing. He had his fair share of publishing disappointments and frustrations, but in the end he triumphed. He emerged from the publishing labyrinth with the material and the players he had known from the very outset were his special province all still intact.”

Nemec shared a final remembrance of Salin with the audience: “Tony really was, as he billed himself as a teenager, ‘Mr. Baseball’ when it came to trivia. He never pushed it on a national level, never would enter formal trivia contests and such, but he would forever come up with great nuggets. The thing you had to accept, though, with Tony was he would never give any additional clues once he had laid one of his gems on you. There was always this elfish smile followed by, ‘Sorry, that’s all the information I’m going to give you.’

“Here was Tony at his best. It formed the basis for a kind of story question that I later refined a bit and used in different ways in two different books. What two Hall of Fame pitchers were born the same year, just two months apart, and won well over 200 games each after spending most of their careers with the same major league team? The clues are that despite pitching for the same team most of their careers, they were never teammates, either in the majors or the minors, and never pitched against each other, either in the majors or the minors. Sounds impossible, right? It gets better. The younger of the two, albeit by two months, won his last major league game before the older of the two won his first. And as Tony would say, if you’re out there now thinking of grabbing me by the throat and shaking some more clues out of me, sorry, that’s all the information I’m going to give you.”

[The answer to this unique trivia question is provided at the conclusion of the Induction Day report.]

Keynote Address: Robert Elias

Robert Elias, delivering Keynote Address at the 2003 Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day

The 2003 Keynote Address was delivered by Mill Valley, California resident Robert Elias, who is Professor and Chair of the Politics Department at the University of San Francisco, where he also founded the Legal Studies and the Peace & Justice Studies programs. A former college baseball player who was once offered a contract by the San Francisco Giants, Elias edited the book Baseball and the American Dream: Race, Class, Gender and the National Pastime (2001). He has been the editor of Peace Review for over ten years and has been active in the peace, civil rights, and anti-apartheid movements. He was a member of the “Baseball for Peace” tour of Nicaragua in 1987, in which war-torn baseball fields were repaired and the sport was used to build goodwill between the American and Nicaraguan peoples. Elias is currently completing research on Curt Flood and on baseball and the Cold War.

Elias began his talk by acknowledging the 2003 inductees to the Shrine of the Eternals: Jim Abbott, Ila Borders, and Marvin Miller. “Their experiences also relate directly to my theme,” Elias remarked. “In their cases, on issues of gender, class, and physical difference, they illustrate both the potential and the limits of the American dream.” Elias followed with a commentary on how throughout the evolution of baseball, key American issues have been played out, including politics and nationalism; labor-management conflicts; class and economic inequalities; and race, ethnic, and gender relations.

See below to view the complete text of Robert Elias’ Keynote Address.

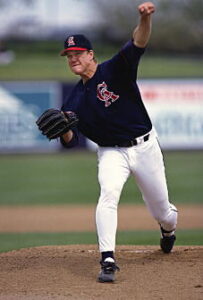

Jim Abbott

The afternoon’s first inductee, Jim Abbott, was introduced by veteran sportswriter Jim McConnell, a journalist for over 30 years. McConnell began his career with the now-defunct Pomona Progress-Bulletin and currently works for the San Gabriel Valley Newspaper Group, which includes the Pasadena Star-News, Whittier Daily News, and San Gabriel Valley Tribune. Along the way, McConnell has garnered numerous awards from places as diverse as the Associated Press, the California Newspaper Publishers Association, the Society for American Baseball Research, and the Los Angeles Press Club.

Jim McConnell, introducing Jim Abbott

McConnell began his introduction with a humorous anecdote: “You know here in Los Angeles for a long, long time, we had a fellow named Biff Elliot. And like so many people in Los Angeles, he worked in show business as an actor in small parts. If you’ve ever seen the old Star Trek where the crew man gets eaten by a rock about two minutes into the show, that’s Biff Elliot. I should also tell you that Biff collected sound bites for Associated Press Radio, which is where he’s going to come into our story. And for the purposes of our New York contingent, Biff is the brother of New York sportscaster Win Elliot.

Biff was really the bane of existence for sportswriters here for a long time. He had the remarkable knack for asking the wrong question at the wrong time. Anyway, go back with me now to the spring of 1989, Anaheim Stadium. Jim Abbott has just pitched a complete game victory in his rookie year, and sportswriters have gathered around his locker. Biff comes in with his tape recorder, pushes his way to the front, and offers the following observation: ‘Jim Abbott, you’re doin’ a great job of handling your handicap.’ And Jim Abbott, without hesitating, shoots back: ‘And you’re doin’ a great job handling yours.’”

In preparing his remarks, McConnell indicated that he had informally polled a dozen sportswriters and it was unanimous that Jim Abbott was their best interview on the Angels in the years he played for them; several of the writers described him as their best interview ever.

McConnell briefly discussed Abbott’s career highlights, including his 18-win season for the Angels in 1991 and his no-hitter for the New York Yankees in 1993. “The Jim Abbott story is about a lot more than numbers,” McConnell noted. “His modesty is kind of a legend among sportswriters. In fact, after the no-hitter, he spent a considerable amount of time talking about what a great job the grounds crew had done fixing the Yankee Stadium infield. And you have to know Jim to know that he was very sincere when he did that.”

“I have met the man,” added McConnell, “I have studied the record, and to me he is a hero. Not one of our manufactured media heroes, not Roy Hobbs. We’re talking about a real hero here. His sincerity shines through in word and deed. You mention the word ‘disability’ to Jim and he’ll come right back at you by counting his blessings, and I’m sure he does every night.”

McConnell concluded by sharing remarks made to him by former Angels pitching coach Marcel Lachemann, who worked closely with Abbott in Anaheim: “Lachemann told me Jim Abbott had the most complicated mechanics of any pitcher he’s ever worked with. Pitching, as you may know, is all about balance and leverage. So if you take the case of Jim Abbott, try tying your non-pitching arm to the side of your body and then pitching off the mound. That would approximate Jim Abbott’s delivery. Lachemann also said that Abbott was the most courageous athlete he’d ever seen. He said he was a very accomplished fielder, but the reality was this: In the event of a line drive hit back through the box at 120 miles an hour, there was no way Abbott was going to be able to get the glove up to protect himself. Lachemann said it was like if you stood at the end of a shooting gallery without a bulletproof vest.

“So I think with that, we really have arrived at the true bottom line about Jim Abbott. Jim, like all the Shrine of the Eternals inductees, past and present, is a profile in courage. And I know he won’t accept that judgment, but it really is unavoidable. The word is courage — not just the physical act of risking serious injury on every pitch, but the courage to carry on with his big league dreams despite those around him who murmured that most destructive of words, impossible. By merely walking between those two white lines, he made baseball a better game and moved it closer to our American ideal of justice and fair play.”

Jim Abbott

Although Jim Abbott was unable to personally attend the ceremony due to a previous commitment in his home state of Michigan, his acceptance speech was videotaped prior to Induction Day and was played following McConnell’s introduction. Abbott thanked the members of the Baseball Reliquary who voted for him and acknowledged several people who were instrumental in the success of his athletic career. “I had remarkable support,” Abbott stated. “My mom and dad were wonderful people who taught me how to play baseball in a little different way and took the time to kind of creatively think of a way for me to play catch. You know, the way I learned to switch the glove on and off is the way I learned to do it with my dad.”

Others that Abbott cited as being particularly supportive included his baseball coach at the University of Michigan, Budd Middaugh, and the Toronto Blue Jays organization, notably head scout Don Wilke and general manager Pat Gillick, who drafted him out of high school. Abbott also thanked the California Angels, who drafted him out of college and gave him the opportunity to pitch in the Major Leagues.

On his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals, Abbott offered these final thoughts: “I feel exceptionally honored that someone would feel that I made a contribution to the game of baseball, because I feel like the game of baseball gave me so much, took me to so many great places, introduced me to so many great people. And that someone feels like I gave something back makes me feel awful proud. I hope my career can serve as a testament to life’s possibilities and also to the fact that the only real handicaps in life are the limitations we place upon ourselves.”

Ila Borders

The second inductee for 2003, Ila Borders, was introduced by Jean Hastings Ardell, an award-winning freelance writer whose work has appeared in book form in the 1994 anthology Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend: Women Writers on Baseball, and in publications such as Elysian Fields Quarterly, the Los Angeles Times, and The Sporting News. Her nonfiction book about women and baseball is forthcoming from Southern Illinois University Press.

Jean Hastings Ardell, introducing Ila Borders

A resident of Corona Del Mar, California, Ardell opined that “while Organized Baseball has reluctantly accepted and later embraced players who are Jewish, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and even Australian, women have remained the game’s last outpost regarding discrimination. For lovers of a good baseball tale, this is a loss, because the story of women in baseball embodies the classic theme of literature: Somebody wants something that is denied them and they set out to find a way to get it. Such is the story of left-hander Ila Jane Borders, who grew up dreaming of playing Major League baseball. Hers is a story of denial and perseverance, of fighting through the same barriers each step along the way. If you want to know how far women have come in this country, and how far they have still to go in search of a fair shake at gender equity, Borders’ story will suffice.”

Ardell then proceeded to chronicle Borders’ competitive hardball career, from Little League through middle school, high school, and college, and into the ranks of professional baseball with the independent Northern League. Highlights along the way included being the first woman to receive a college baseball scholarship (1993, Southern California College), the first female pitcher to win a men’s college game (1993), and the first female to win a men’s regular-season professional game (1998). “She proved that girls are not too weak or too fragile to play the game, and that some definitely don’t throw like a girl,” Ardell added. “Her presence on the diamond educated both the fans in the stands, the coaches, and the boys and men she played with and competed against — at least those open to change, who learned to respect women in a deeper way. As her last manager [Borders retired from professional baseball in 2000], the Zion Pioneerz’ Mike Littlewood said, ‘Ila was one of the most courageous people I’ve ever met or seen play the game.’”

Ardell concluded her introduction with this assessment of the pitcher’s career: “Borders also reminds us of the tremendous changes that occurred for girls and women over the last quarter of the 20th century. Her career serves as a definitive marker of those changes, from the passing of Title IX, which opened the way for her to play Little League, and the affirmative action and federal mandates that helped us grow familiar with the sight of a woman in a man’s field, whether the law, medicine, or baseball’s front offices, through her list of first-woman ever achievements. So it is fitting that we invite Ila Borders into the Shrine of the Eternals — this independent, pony-tailed pitcher with a fierce dream. She’s in good company with the Shrine’s other renegades — people like Satchel Paige, Jim Bouton, Pam Postema, and Jimmy Piersall — who each fought the odds for their piece of the game. In honoring her today, we begin to articulate her story and keep it alive. Organized Baseball could learn a lot from Ila Borders’ story; so could we all.”

Ila Borders

Ila Borders walked to the podium to a standing ovation from the audience. She described her life as being “a fairy tale” and offered thanks to her parents, both of whom were in attendance. Her father, Phil, who had played professionally himself, worked closely with her on the “mechanics” of the game since she was a child. Her mother, Marianne, drove her to games and practices, and it was from her that she inherited her “heart” and drive to succeed. Borders also acknowledged the presence of Mr. and Mrs. Jim Wadley, former owners of the Duluth-Superior Dukes of the Northern League, for whom she enjoyed her longest stint in professional baseball. She thanked the Wadleys for allowing her to become a starting pitcher for the first time at the pro level, and then proudly flashed her 1997 Northern League championship ring, which she earned as a member of the Dukes.

Borders talked about her future outside of baseball, as well as the possibility of a return to the professional game: “Right now I’m training to be a firefighter. I’m hoping after I get out of the firefighting academy next June to play ball for one more year. I think I have one more year in me. I’m in the best shape of my life right now, and I think I know how to deal with the media a little bit better now. [Considerable audience laughter] That was extremely hard. I was under so much stress then. Now I can just go out there and enjoy the game. So hopefully a year from now, you’ll be hearing about me playing again.”

Marvin Miller

The final inductee for 2003, Marvin Miller, was introduced by baseball lawyer Richard Moss, whose background in professional baseball dates to 1967, when Marvin Miller invited him to join the Major League Baseball Players Association as legal counsel. Along with Miller, Moss was intimately involved in many of the pioneering legal decisions as they pertained to the game’s development in the late 1960s and 1970s. In fact, he argued all of the union’s legal and arbitration cases during his 11-year tenure with the Players Association. Moss became interested in labor law while attending the Harvard Law School. Following a two-year stint in the Army, he practiced for a brief time in a small Pittsburgh law firm before joining the Steelworkers Union, first as assistant general counsel and later as associate general counsel in charge of the legal department at the union’s international headquarters. Since leaving the Players Association in 1977, he has represented numerous professional baseball players and has also taught Sports and the Law at the University of Southern California.

Richard Moss, introducing Marvin Miller

A resident of Marina Del Rey, California, Richard Moss talked about his 43-year relationship with Marvin Miller, and described the abilities of the man who turned a company union into a meaningful agency of representation: “Marvin was really perfect for the task. He’s a very smart guy, but there are a lot of smart people out there. He’s a great negotiator, but there are a lot of people who know how to negotiate. But what he added to the mix was this wonderful talent that he has of being able to explain sometimes very complicated things to people in a simple and understandable way. He is a great communicator. The players at the time, 1966, were a pretty conservative group of people. There were a few Jim Boutons around, but not many. But they had been indoctrinated — brainwashed — in a couple of ways. Players at that time were constantly told that they were lucky to be playing baseball and making money doing it. The average salary then was $18,000, the minimum salary was $5,000. But they were told if it wasn’t for baseball, they would probably be driving trucks. Or if they were black, they were told they’d be picking cotton. And I mean that literally. There are many stories like that.

“Marvin helped the players understand that individually they had very little power, but collectively they could change the system; they could create a more equitable world in terms of their conditions of employment. Marvin helped them understand something very basic, too, about labor organizations and success, and that concerns solidarity. If you stick together, you can accomplish things, and if you don’t, you won’t. And that’s what distinguished the Baseball Players Association from comparable unions in other sports.”

Moss concluded by stating, “Marvin deserves every honor and accolade that he has been given, and more,” and then invited his former colleague to the podium to accept his induction.

Marvin Miller

The 86-year-old Miller was greeted with a standing ovation as he walked to the stage. He proceeded to thank several people who provided support to him over the years, most importantly his wife of 63 years, Terry Miller, who was in the audience, having traveled to Pasadena with her husband from their home in New York City for this occasion. Miller also cited fellow Shrine of the Eternals inductee Jim Bouton for his important role in the early years of the Players Association. “Bouton is, of course, well known as a fine pitcher for the Yankees and other teams, as well as an author, public speaker, and innovator,” Miller remarked. “But not so well known is that he was one of the earliest baseball union activists. To the best of my knowledge, he was the first one to actually campaign for the office of elected player representative.” According to Miller, Bouton’s activism had a significant impact on the players’ view of their union, resulting in their revelation that a union was a method by which they could improve a set of poor working conditions.

Miller chuckled about his initial response to being elected to the Shrine of the Eternals: “When I first received the telephone call about my election to the Shrine of the Eternals and received some literature about the Baseball Reliquary, I felt very honored to be included, but do admit some doubt as to the accuracy of the time span those words ‘Shrine of the Eternals’ suggest. With regard to Reliquary, I rushed to the dictionary and saw the definition was a depository for a relic. As for the age aspects of a relic, I’m clearly eligible. Seriously, I am probably among the oldest of the living persons elected to the Shrine of the Eternals.”

Miller then addressed what he perceives as “inaccuracies, distortions, and biases that increasingly seem to invade aspects of our lives. The world of baseball is not exempt from this; in fact, baseball is a prime example of mythology often being honored in preference over facts.” He cited as an example a general perception amongst fans, ownership, and media that baseball is a strike-prone industry, which has been characterized by endless strife since the inception of the Players Association. This viewpoint was bolstered at the end of 2002 when a settlement of baseball negotiations was made and Commissioner Bud Selig announced that “this was the first settlement in the history of baseball without a strike.” Miller chastised Selig for being part of this mythology and for not knowing the facts.

In explaining, Miller noted that, historically, when a union arrives, wrenching changes often lie ahead for the employer. Therefore, it is not surprising that strikes and stoppages occur, often for decades. “But in Major League Baseball, when the change to union status began in the mid-’60s,” Miller argued, “the potential for conflict and strikes was far greater than in any other organized industry. In other industries, the employees were not owned by their employers; they were not property; they could not be traded or sold for cash. The employees could not be victimized, blacklisted, or denied employment. But in baseball, all these conditions existed for about 100 years. And yet, even though changing these entrenched baseball practices involved more extensive and far-reaching changes than in other industries, they were negotiated in baseball with a minimum of lost time and with significantly less lost time than in any other industry. I know that this runs contrary to what the general impression is.

“To be specific, in the first 15 years of collective bargaining in Major League Baseball, from 1966 to 1981, five basic collective bargaining agreements were negotiated, involving the greatest improvements of the working conditions of the employees than those achieved in any other American industry in a comparable period of time. They included, of course, the end of the reserve clause; the introduction of salary arbitration; the introduction of impartial arbitration of disputes involving interpretations of the contracts; the introduction of the players’ right to veto trades; and much, much more. In those same 15 years, five pension and insurance agreements were negotiated, vastly improving all the benefits and adding many new ones. And all of this was done with lost time of exactly nine days in 1972. In those first 15 years, nine days of stoppage represented three-tenths of one percent of the days’ work.” In underlining the inaccuracy of Commissioner Selig’s statement, Miller further observed, “Baseball might turn out to be the most peaceful of any United States industry in converting from non-union to union status.”

Miller then addressed concerns about the current state of baseball, specifically the impact high salaries have had on the game and the perception that the union has ruined baseball. He began with an analysis of how baseball salaries are set: “Well, for one thing, the union doesn’t negotiate them. This is not General Motors, this is not United States Steel. The union negotiates one salary with the owners — the minimum salary in Major League Baseball. Now, the minimum salary affects, on the average, perhaps one to two players per club each year. In addition, there is salary arbitration for some players when the player and the club have been unable to agree on the salary for the coming year. In almost any year, not more than 15 to 18 players have their salaries set by impartial arbitrators. So you have the minimum salary affecting one or two per club, with salary arbitration setting the salaries of less than two per club. And all other salaries in Major League Baseball are, and always have been, determined by the owners.

“Now I stress this because I get these ca

lls saying how can the union keep pressing for higher salaries, and when I explain the union doesn’t negotiate salaries, I get the feeling that they think I’m lying. The fact of the matter is that the union doesn’t even know what those salaries are until after they are negotiated, after the club official and the player have signed the contract and a copy is sent to the commissioner’s office and a copy is sent to the players’ union. That’s the first time that the players’ union knows about these high salaries that allegedly the union is negotiating.”

Miller concluded with his views on the economic status of the industry: “When the union began in 1966-67, revenue of the 20 Major League clubs was a little under $50 million a year collectively; in 2002, the revenue of the 30 clubs was a little over $3 billion. In 1966-67, after the clubs paid all the salaries, they had almost $40 million left for all other expenses and profits. In 2002, they had $1 billion left after all those salaries. Does that sound like a ruined industry?”

Another way to view the economic well-being of baseball is to examine the value of its franchises. Miller noted, “In 1962, the New York Mets cost its new owners $2,600,000. In 2002, after 36 years of the union, the two Mets owners, who were parting company, got into a dispute as to whether the franchise was worth $300 million or $400 million. The Boston Red Sox franchise recently sold for over $400 million, and the New York Yankees, while not for sale, are estimated to be worth more than that.”

[For further observations from Marvin Miller, we are pleased to publish David Davis’ interview with the former Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, conducted shortly before his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals. To view the complete text of the interview, click on the following link: Marvin Miller Interview.

Benediction

As he usually does, the Master of Ceremonies, Terry Cannon, concluded the Induction Day festivities with a benediction or parting thought: “Two hours ago, we began with a tribute to the greatest of all fans, Hilda Chester, and now I would like to end by reading a brief section from a book written by a fan, not a professional writer, named Art Hill. The book is entitled I Don’t Care if I Never Come Back: A Baseball Fan and His Game, and was published in 1980. In the following passage, the author examines his unique relationship with the game, and I think his experience in the thrall of baseball will be recognizable to many of us similarly afflicted.

“I wish I could explain my lifelong obsession with baseball. But it is like trying to explain sex to a precocious six-year-old. Not that I have ever done this, but I assume the child would say something like ‘Okay, I understand the procedure. But why?’ There is no answer for that. You have to be there.

“With baseball, too, you have to be there. But once you have been there, and bought it, you are likely to remain hooked for the rest of your life.

“If baseball’s appeal is hard to explain, there is no shortage of people who are willing to try. A writer named Gilbert Sorrentino had a go at it in the New York Times. Baseball, he said, is played in a framework of space rather than time. He said that in McLuhan’s terms it is a ‘hot’ game, that it is ‘filled with high-definition performances,’ that ‘anything can happen,’ literally, because the game’s length is not controlled by a clock. He did not say, because a careful writer will go to any length to avoid using a cliché, that the game is never over until the last man is out. But I think maybe that’s what he meant.

“And here is an article someone has sent me from a scholarly magazine called Critical Inquiry. The author, Dennis Porter (professor of French and comparative literature at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst), feels strongly that baseball shares a hidden structure with the Russian fairy tale, and that the game is ‘best understood as a nonverbal folk form.’ He could be right, although I almost never think of it that way.

“I don’t claim to know what lights the spark. I know only that every winter, when baseball is dormant, I feel as if it’s gone forever. And every spring, the first time I see a shortstop charge a slow bounding ball, short-hop it on the edge of the grass and in the same motion throw to first, beating the runner by a half-step, I rediscover its magical beauty and I marvel at my good fortune.”

Keynote Address

by Robert Elias

July 20, 2003

Thank you. I’m honored to be here. I’d like to thank Terry Cannon and the Baseball Reliquary Board for inviting me to speak. I was thinking about the artifacts collected by the Baseball Reliquary. I was reminded of the pitcher Don Sutton’s response to accusations that he used a foreign substance on the ball. Sutton said, “Actually, that’s not true. Vaseline is manufactured right here in the U.S.” Certainly, one of Sutton’s Vaseline jars belongs in the Reliquary collection.

It’s commonly assumed that the Baseball Reliquary was founded by Terry Cannon. That’s also not true. It’s just one of those myths passed down through the years like at that other museum, in Cooperville or Coppertown, wherever it is. . . Cannon was a decorated Civil War General and the Reliquary thought he’d sound better than the real founder, who actually laid out the original plans for the Reliquary at an abandoned brewery in Milwaukee: his name, of course, is Bud Selig. Unfortunately, Bud couldn’t be with us today. . .

Let me begin with a few words about today’s Shrine of the Eternals inductees. For me, the choices are serendipitous. I’ve recently begun some writing on Pete Gray, the one-armed outfielder who played for the St. Louis Browns in the 1940s. While Gray’s story of overcoming his physical difference is remarkable, even more impressive and inspiring is the story of Jim Abbott. My older son, Andre, accumulated a number of baseball autographs growing up. One of his most cherished is the one from Jim Abbott.

I also have a young daughter, Madeleine, and I’ve wanted to make sure that she, as a girl, was never discouraged from playing baseball. Thus, for the last couple of years, I’ve had a postcard taped up on her bedroom wall of a woman pitching in a game. That woman, who serves as a model for my daughter, is Ila Borders. By the way, I have another young child, Jack, and I make him watch the Detroit Tigers and New York Mets. To paraphrase Toots Shor, “I want him to know life. It’s a history lesson. This way my son will understand the Depression.” As you can probably tell, I have too many kids. . .

In any case, I’ve also been doing research on Curt Flood and his impact on professional sports. But you can’t talk about Flood without also talking about the man that Hank Aaron claimed is as important to baseball history as Jackie Robinson. Of course, that man is Marvin Miller, who I admire immensely. I feel fortunate to be able to meet our inductees. Their experiences also relate directly to my theme. In their cases, on issues of gender, class, and physical difference, they illustrate both the potential and the limits of the American dream.

As Terry mentioned, I’ve written a book, Baseball and the American Dream, and teach a course on that subject at the University of San Francisco. Neither the book nor the course focuses on baseball statistics or records. Instead, I’m more concerned with baseball as a reflection of American history and culture.

In her book, Foul Ball, Allison Gordon wrote, “I once stood outside Fenway Park in Boston, . . . and watched a vigorous man of middle years helping, with infinite care, a frail and elderly gentleman through the milling crowds to the entry gate. Through the tears that came unexpectedly to my eyes, I saw the old man strong and important forty years before, holding the hand of a confused and excited five-year old, showing him the way. Baseball’s best moments don’t always happen on the field.”

Yes, baseball’s best moments don’t always happen on the field. Historian Peter Bjarkman has written that baseball “. . . is a game which surely does not mean half of the things we take it to mean. But then again, it probably means so much more.” Arguably, baseball reflects some of the nation’s noblest aspirations. To understand this, we should consider baseball’s relationship to our quintessential national quest: the pursuit of the American dream.

A Dream Deferred?

We all know the basic ingredients of the American dream. However we precisely define it, the dream makes the country special: it nourishes the American people, it seduces foreigners to our shores, and it spreads the American way far beyond our own borders. Support for the American dream has been widespread. But some of the praise is revealing. For example, one advocate claimed that: “This American system of ours. . . call it Americanism, call it capitalism, call it what you like, gives to each and every one of us a great opportunity if we only seize it with both hands and make the most of it.” Unfortunately, those are the words of the famous American gangster, Al Capone. What does that tell us?

We might also wonder how much the American dream has been a reality, and for whom? To what extent have its promises been fulfilled? People worry about this, and for good reason. Many don’t experience the U.S. as a land of opportunity. Even if the dream were more widely experienced, some worry about the values it asks us to live by — materialism, hyper-competition, excessive individualism, and so forth. In the end, the American dream may not be so much the inevitable reality but rather the dream and also its contradiction. Which one will prevail?

Baseball as Cultural Mirror

What does this have to do with baseball? To more specifically examine the ingredients and performance of the American dream, we could choose from many mirrors of our nation. Sports is one possible mirror. But one American sport surpasses all others in reflecting U.S. society: baseball. Roger Angell has suggested that, “Baseball seems to have been invented solely for the purpose of explaining all other things in life.” Well, perhaps not everything. But quite a lot.

About baseball, Walt Whitman said: “Well — it’s our game; that’s the chief fact in connection with it: America’s game. . . it belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly as our Constitution’s laws; is just as important in the sum total of our historic life.” Bart Giamatti claimed that baseball “is the last pure place where Americans can dream.” George Grella says that, “. . . baseball, not football, will always be our National Pastime. . . [It] speaks as few other human activities can to our country’s sense of itself. . . and should be compared not only with other sports, but with. . . our painting, music, dance and literature. . . baseball embodies the central preoccupations of the cultural fantasy we think of as the American Dream. . .”

But what, precisely, is the relationship? Does baseball illustrate the American dream, and provide us lessons for how to achieve it? Is baseball itself a route to the American dream? Does the game challenge the American dream and its driving values? Is baseball a narcotic for distracting us from the realities of the American dream? Or does baseball serve as a refuge from its endless strife and accumulation?

Maybe baseball is no single one of these things. The game has represented different experiences for different groups at different times and places. Baseball has a long tradition dating from the earliest years of the American republic. It has uniquely mirrored the trends in the culture at large. Arguably, Americans should care about baseball because it has been, and remains, a measure of the health of our society.

A Field of Dreams?

With what ingredients of the American dream have baseball been associated? Francis Miller claimed that, “Baseball is democracy in action: in it all men are ‘free and equal,’ regardless of race, nationality or creed. Every man is given the rightful opportunity to rise to the top on his own merits. . . It is the fullest expression of freedom of speech, freedom of press, and freedom of assembly in our national life.”

David Voigt claims that, “. . . baseball kept alive Horatio Alger’s myth that a hungry, rural-raised, poor boy could win middle-class respectability through persistence, courage and hard work.” Baseball has been “. .. a vehicle of assimilation for immigrants into American society. . . [and has] kept the myth of the American melting pot alive. . .” Immigrant leaders have advised their peoples to learn the national game if they wanted to become true Americans. Buster Olney has observed that, “More than a half-century after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, America celebrates his legacy. . . When Orlando Hernandez, from Cuba, signed with the Yankees, catcher Joe Girardi noted the variety on New York’s pitching staff: Kansas City Irishman David Cone, Andy Pettite of French descent, Panamanian Ramiro Mendoza, Hideki Irabu of Japan. And finally, David Wells, who’s probably from Jupiter.”

For those on the sidelines, baseball has helped assimilate fans and develop individual identities. The fans’ affiliations with their teams have often exceeded their attachment to their church, trade, political party — all but family and country, and even those have sometimes emerged all wrapped up in baseball.

Baseball has been used to demonstrate the benefits of play, team spirit, and sportsmanship. The game has been prescribed as a preventative against things such as crime, violence, delinquency, and even the stresses of modern life. Baseball has been widely represented in our language and literature. It exudes beauty and grace, and has been described as “poetry in motion” and “a work of art.” The game has been linked to patriotism and nationalism, and to American prestige at home and abroad. For these and other reasons, baseball has been a symbol of Americanism.

Second Thoughts on the Baseball Dream

Of course, baseball’s long association with the American dream might also mask some uncomfortable realities. For example, the historian, Harold Seymour, worried about those, “who regimented [baseball]. . . with their own ideology, to impose values that would make the growth of capitalism easier by creating an opiate to distract citizens from imperfect working, learning and living conditions.”

David Voigt argues that, “In baseball and the broader society the opportunities for some groups have been few rather than many, and for some races, virtually all access has been choked off for long periods. As some of the barriers to the American dream have fallen in more contemporary times, we nevertheless often find, inside and outside baseball, that progress still falls well short of our American ideals.” While the stories of African-American, Asian-American, and Latino-American baseball players are often inspiring, their paths to success sometimes seem more in spite of the American dream than because of it.

Some worry about the lingering obstacles to women’s participation in baseball. Susan Berkson has written that, “Ken Burns [in his Baseball book and documentary] calls baseball a metaphor for democracy. But he’s wrong. Instead, it’s a metaphor for sexism. The great theme is that it’s a boys game; women have been shut out again and again.” Although women have historically been more involved in baseball than we commonly assume, the biases against them largely remain and also extend to other baseball roles. The former umpire, Pam Postema, who was driven out of baseball, summed it up in the colorful title of her book: You’ve Got To Have Balls to Make It In This League. We have to wonder whether baseball can be a part of the American dream for women.

Economic inequalities also prevail in baseball on several levels, between minor leaguers and major leaguers, players and owners, big market owners and small market owners, and so forth. As John Thorn has suggested, “The lie of baseball is that it’s a level playing field. . . That all the inequities in American life check their hat at the door. That they don’t go into the stadium. That once you’re there, there’s a sort of bleacher democracy, that the banker can sit in the bleachers and converse with the working man next to him. This is a falsehood. You have class and race issues that mirror the struggle of American life, playing themselves out on the ballfields.”

Gai Berlage worries about the corporate values that high-powered professional sports, such as baseball, routinely ingrain into children. Others warn us about baseball’s increasing control by media corporations with little real interest in the game. According to Peter Carino, the building of new stadiums such as Camden Yards “demonstrates. . . what a grand ballpark can mean to a city and the game, [but] it also illustrates the more unsavory elements marking the culture this dream represents: the machinations of power brokers, the sweetheart subsidies from politicians to the private sector, and the class structures that belie the nation’s claim to democracy.” Tom Goldstein claims that baseball is being run “by network executives, marketing consultants, and PR ‘wizards’. . . Baseball is America’s newly found ‘cheap’ natural resource. Our communities have become strip mines, and the fans are the precious commodity to be plundered.”

Steve Lehman worries that the growing economic disparities in Major League Baseball are rationalized by false appeals to the American dream. For example, when he managed the wealthy Los Angeles Dodgers, Davey Johnson claimed that: “Parity is not the American way. The American way is to dominate somebody else.” Lehman disputes such descriptions of “the American way.” “They’re more like the natural tendencies of monarchies or fascist states than democratic ones,” Lehman says, “and more like football than baseball.” Perhaps, then, we have more than one American dream. Which one do we want to live by? Must we choose between a football American dream and a baseball American dream, as Lehman implies, where football is the sport for the nation we are and have become while baseball is the sport for the nation we were and could be?

The Lure of Nostalgia

As we search for the genuine “American way,” it’s tempting to think that if only we could return to the “good old days,” our problems would be solved. As one of our oldest and most unchanging institutions, baseball oozes nostalgia. It takes us back to a simpler time when things seemed less fleeting and confusing. As songwriter Paul Simon asked: “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? Our nation casts its lonely eyes to thee.”

In our alienated culture, we long for community. We rally around things that can unite us and make us feel good about ourselves and our society. The danger, however, comes when nostalgia is used to sanitize the past and divert us from present realities. Is baseball once again the “national pastime,” or is it merely the “national past tense,” nostalgically describing an idealized, bygone era?

Ron Briley claims that, “in [Mickey] Mantle’s final days, many of his admirers recalled lost youth and yearned for [the good old days]: an America free from crime, decaying morals, culture wars, economic insecurity, and social conflict.” But this, Briley says, was “mere wishful thinking for Americans uncomfortable with changing perceptions of race, gender and class.” It was a longing for “the way we never were.”

Each year, thousands of Americans make a pilgrimage to Cooperstown, New York and Dyersville, Iowa (where Field of Dreams was filmed). In his study of those sites, Charles Springwood found that a nostalgia for a lost America motivated far more visitors than a quest for baseball history. “Visitors [to Cooperstown and Dyersville],” he says, “experience. . . a kind of personal purification where they make contact with the simple life, the work ethic, childhood, fatherhood, marriage, the importance of family and home, the meaning of the father-son bond.” The “Field of Dreams” lives on beyond the film that created it. In a world where life has increasingly become a movie, the field is real to visitors as long as it remains true to the film. Both Cooperstown and Dyersville keep alive a part of the American dream.

But for whose interests? William Fischer worries about the recent proliferation of baseball films and literature. “It seemed,” he says, “as if baseball. . . was now being improperly used as a symbol of moral purity, as a romantic bedrock in [our] modern days of evil. In the book The Natural, for example, Roy Hobbs strikes out and is left in ignominious defeat, a human being swallowed by his human weaknesses. And yet [in the movie, this] was transformed into a ‘feel-good’ story about a ‘can-do’ America.” Fischer says that American politics since the 1980s has pushed the themes of “Bringing America Back” and “Family Values,” while watching the middle classes shrink and corporate values flourish. . . [A] society emerged that is less human, and more alienating and artificial. . .” To compensate for this decline, Fischer argues, we were given the nostalgic symbol of baseball.

Baseball’s Deep Resonance

But perhaps baseball can instead play a more concrete and positive social role. We shouldn’t sentimentally over-exaggerate baseball’s influence. Even so, many people find themselves confused about their society and world. They view life as chaotic, lacking any meaningful shape. If in the twentieth century, baseball provided a semblance of community in large, increasingly alienated urban centers, then in the twenty-first century perhaps the game can help us make sense of an increasingly complicated and fast-paced age. It may serve as a metaphorical ointment for those wounded by our contemporary society.

We want baseball to be good, we want it to be pure, we want to be able to keep loving it. For some of us, it’s our refuge, our salvation. Some people feel as intensely about baseball as they feel about their nation: they’re baseball patriots. Baseball remains deeply ingrained in the American character. According to Joseph Sobran, “Our deepest norms of order can still be seen in operation on the diamond when they’ve been adulterated everywhere else. Baseball is our Utopia. . .”

In baseball’s evolution, we see key American issues being played out: politics and nationalism; labor-management conflicts; class and economic inequalities; religion and spirituality; expansion and foreign affairs; race, ethnic, and gender relations; and much more. It reflects a host of age-old American tensions: between workers and owners, scandal and reform, urban and rural, the individual and the community, and so forth. In many ways, baseball is a barometer for the society.

It’s no coincidence, as Frank Deford has suggested, that the last two words of the national anthem are “play ball.” Baseball still strongly reverberates in America. If it also has its shortcomings, then fixing them can enrich and even rescue the nation. Bill Lee once said: “Baseball is the belly-button of our society. Straighten out baseball, and you straighten out the rest of the world.”

For example, baseball has been racist, yet — through Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey — it also led the way for greater integration not only of American sports but also of American society. Likewise, baseball has been sexist, yet it was the first sport to allow women to play professionally, and to allow girls to play in the little leagues. Baseball has been classist, and yet — through Curt Flood and Marvin Miller — it also pioneered the end to wage slavery not only in baseball but in all professional sports, and it might yet serve as a model for America’s broader labor movement. Consider Flood’s explanation for challenging the reserve clause: “I guess you really have to understand who that person, who that Curt Flood was. I’m a child of the sixties. . . a man of the sixties. During that. . . time this country was coming apart at the seams. We were in Southeast Asia. . . Good men were dying for America and the Constitution. In the southern part of the U.S. we were marching for civil rights and Dr. King had been assassinated, and we lost the Kennedys. To think that merely because I was a professional baseball player, I could ignore what was going on outside the walls of Busch Stadium [was] truly hypocrisy and now I found that all of those rights that these great Americans were dying for, I didn’t have in my own profession.” This suggests a sport that’s deeply intertwined with its times. Baseball has played a transformative role in the past; it can do so again in the future.

Restoring Baseball’s American Dream

How can we unleash baseball’s potential for progress? For example, if Jackie Robinson opened baseball to people of color, and if Curt Flood brought some control of the game to the players, how and who can return the game, now, to the fans? In our spectator culture, where most of us watch our games and society passively on the sidelines, how can fans and citizens be brought into the center of the action?

Peter Gammons argues that, “Baseball can assume its place as the sport of the American dream, but it will not happen by looking back. If indeed baseball is on the brink of a renaissance, then what it needs is a creative vision.” But that “creative vision” will not likely emerge from baseball’s ruling establishment. A new direction for baseball can come, however, from baseball players and their union, and from baseball fans and their communities. Baseball could provide initiatives to help reform not only the national pastime but also American society. It could lead the way on worker’s rights and in revitalizing the labor movement. It could promote genuine racial equality and improve race relations. It could push for serious enforcement of anti-trust laws and provide new models of public ownership for teams and other corporations. It could concern itself with its consumers — the fans — as humans and not merely as commodities. It could promote breakthroughs in women’s access to the game and to sports and American institutions, generally. As Kevin Brooks suggests, “For those who have experienced the field of dreams, they should not retreat to their paradise, making it an idol, but rather forsake paradise and live among the people, sharing the good news.” The players have a particular responsibility along these lines.

Grassroots organizations can also play an important role. For example, Ralph Nader’s Sports Reform Project and his group, FANS (Fight to Advance the Nation’s Sports), have put out a Fan’s Bill of Rights. I also recommend Don Weiskopf’s Baseball Play America, SABR (the Society for American Baseball Research), and FAIRBALL, a group begun by the Elysian Fields Quarterly.

Most of all, however, the Baseball Reliquary has been working to bring the game back to the fans and to restore the baseball American dream. It’s helping us to construct a people’s history of not only baseball but also America, to put up against the official story. As an organization run by baseball fans, it’s providing us with a deeper understanding of baseball and its impact on American history and culture.

The Reliquary’s induction criteria stand in bold contrast to the mere compilation of baseball statistics and records. They reward the distinctiveness of one’s play, uniqueness of one’s character, and the person’s imprint on the baseball landscape. They reflect excellence in character or principle, and contributions to developing baseball as an arena for the human imagination. We need only consider the names of the previous inductees to conjure up their unique qualities — people such as Bill Veeck, Jim Bouton, Curt Flood, Pam Postema, Bill Lee, Moe Berg, Dock Ellis, Minnie Minoso, Satchel Paige, and so forth. Not to mention today’s inductees.

Robert Elias, delivering Keynote Address at the 2003 Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day

(photo courtesy of Larry Goren)

In conclusion: At its best, perhaps baseball is better than American society. As Reggie Jackson once said: “The country is as American as baseball.” Baseball can help make the American dream more worth attaining, and more accessible to more people. There are disturbing signs that America is a culture in crisis. The increasing attempts to impose the American way abroad seem correlated with a growing questioning by Americans of their own society at home. Perhaps America should be looking up to the best in baseball. As journalist Bill Vaughan once wrote: “What it adds up to is that it’s not baseball’s responsibility to fit itself into our frantic society. It’s, rather, society’s responsibility to make itself worthy of baseball. That’s why I can never understand why anybody leaves the game early to beat the traffic. The purpose of baseball is to keep you from caring if you beat the traffic.”

How can baseball help fulfill the American promise? John Thorn put it this way: “Fundamentally, baseball is what America is not, but has longed or imagined itself to be. It is the missing piece of the puzzle, the part that makes us whole. . . a fit for a fractured society. While America is about breaking apart, baseball is about connecting. America, independent and separate, is a lonely nation in which culture, class, ideology, and creed fail to unite us; but baseball is the tie that binds. . . Yet more than anything else, baseball is about hope and renewal. . . This great game opens a portal onto our past, both real and imagined. . . it holds up a mirror, showing us as we are. And sometimes baseball even serves as a beacon, revealing a path through the wilderness.” For those of us pursuing a new and better American dream, and a renewal of baseball as America’s national pastime, it’s a path we should all be gladly taking. Thank you.

Bill Of Rights For Fans (Fight To Advance The Nation’s Sports)

- Fans should influence rules changes.

- Fans have a right to know about the operation and practice of organized sports.

- Fans have the right to purchase reasonably priced tickets and to be treated with courtesy and respect.

- Tickets should be available to everyone and not just the elites.

- Fans have the right to see their interests represented before Congress.

- Fans should have games broadcast the way they want them shown.

- Fans have the right to have their interests effectively expressed in the resolution of sports disputes.

- The interest of fans in the integrity of a team should also be effectively expressed.

- Fans, as average citizens, have a right not to see those in sports treated as if they are above the law.

- Sports entities that rely on public funds have an obligation to serve the public and disclose relevant information.

Induction Day Photographs Courtesy of Larry Goren

Answer to trivia question: Joe McGinnity and Amos Rusie