Dock Phillip Ellis, Jr.

Born 3/11/45, Los Angeles, California

One of baseball’s most controversial and outspoken players of the 1960s and 1970s was right-handed pitcher Dock Ellis, who spent the majority of his 12-year career (1968-1979) with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He also donned the jerseys of the New York Yankees, Oakland Athletics, Texas Rangers, and New York Mets. In that era, a number of black players, emboldened by the civil rights movement, spoke out publicly against what they perceived as widespread racial prejudice in the game. For manifesting their freedom of speech and speaking their minds regardless of consequence, players such as Dock Ellis, Curt Flood, and Dick Allen were labeled as “militants” by the press, the baseball establishment, and many of the white fans who preferred their players to be “good slaves” — docile, humble, and grateful.

One of baseball’s most controversial and outspoken players of the 1960s and 1970s was right-handed pitcher Dock Ellis, who spent the majority of his 12-year career (1968-1979) with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He also donned the jerseys of the New York Yankees, Oakland Athletics, Texas Rangers, and New York Mets. In that era, a number of black players, emboldened by the civil rights movement, spoke out publicly against what they perceived as widespread racial prejudice in the game. For manifesting their freedom of speech and speaking their minds regardless of consequence, players such as Dock Ellis, Curt Flood, and Dick Allen were labeled as “militants” by the press, the baseball establishment, and many of the white fans who preferred their players to be “good slaves” — docile, humble, and grateful.

Controversy followed Dock Ellis throughout his baseball career, yet he steadfastly refused to compromise his principles. Dating back to his formative years in Los Angeles, he refused to play baseball at Gardena High School in protest against the coach’s racism. While in the minor leagues in 1964, he went into the stands and swung a leaded bat at a racist heckler in Batavia, New York.

Perhaps the centerpiece of Ellis’ stormy career came with the Pittsburgh Pirates on June 12, 1970, when he threw a no-hitter against the San Diego Padres while under the influence of LSD. “I can only remember bits and pieces of the game,” Ellis said later. “I was psyched. I had a feeling of euphoria. I remember hitting a couple of batters and the bases were loaded two or three times.” He walked a total of eight batters in what might be described as one of the most bizarre no-hitters ever thrown.

The year 1972 found Ellis back in the headlines when he was maced by a security guard at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium who wouldn’t let him into the Pirates clubhouse. (After an investigation, the Cincinnati club apologized to Ellis and fired the security guard.) Another flap ensued in 1973 when he started wearing hair curlers to the ballpark, after Ebony magazine ran a feature on Ellis’ various hair styles. Supposedly an order came from Commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s office to cease and desist wearing curlers on the field.

Perhaps Ellis’ most startling act occurred on May 1, 1974, when he tied a major league record by hitting three batters in a row. In spring training that year, Ellis sensed the Pirates had lost the aggressiveness that drove them to three straight division titles from 1970 to 1972. Furthermore, the team now seemed intimidated by Cincinnati’s “Big Red Machine.” “Cincinnati will bullshit with us and kick our ass and laugh at us,” Ellis said. “They’re the only team that talk about us like a dog.” Ellis single-handedly decided to break the Pirates out of their emotional slump, announcing that “We gonna get down. We gonna do the do. I’m going to hit these motherfuckers.” True to his word, in the first inning of the first regular-season game he pitched against the Reds, Ellis hit leadoff batter Pete Rose in the ribs, then plunked Joe Morgan in the kidney, and loaded the bases by hitting Dan Driessen in the back. Tony Perez, batting cleanup, dodged a succession of Ellis’ pitches to walk and force in a run. The next hitter was Johnny Bench. “I tried to deck him twice,” Ellis recalled. “I threw at his jaw, and he moved. I threw at the back of his head, and he moved.” At this point, Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh removed Ellis from the game. But his strategy worked: the Pirates snapped out of their lethargy to win a division title in 1974, while the Reds failed to win their division for the first time in three years.

Unfortunately, the perception of Dock Ellis as a hostile ballplayer overshadowed many of the largely unpublicized acts of charity and conscience which were the hallmarks of his career. Ellis worked for the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, helping to rehabilitate black prisoners. In 1971, he and a group of black athletes started the Black Athletes Foundation for Sickle Cell Research, an organization whose purpose was to lobby and raise money for research and treatment of sickle cell anemia. For his loyalty and charitable acts, Ellis, much like Muhammad Ali, earned the respect of the black community. In poet Donald Hall’s gritty and candid 1976 biography, Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball, fellow ballplayer Willie Crawford expressed his and the black community’s admiration for Ellis: “Dock is the same here as Richie Allen. Because newspapers were trying to make them bad guys in the public’s eyes instead of making them heroes like Jackie Robinson. Jackie Robinson didn’t fight for blacks until he left baseball. Dock made his fight while he has been in baseball even though he put his job in jeopardy. There should be more black athletes doing this.

“At an early age I knew he was searching to really leave his mark in life. He found it in his fight for his people. I know somebody said all the trouble he’s getting into, it really hurt his mother. His mother would talk to me sometimes and say, ‘What’s wrong with Dock?’ I told her he’s fighting for equality for us, for all black people, and the kids that come behind us. That they have the opportunity to express themselves freely. The whole key to success in anything is self-expression.”

Curtis Charles Flood

Born 1/18/38, Houston, Texas

Died 1/20/97, Los Angeles, California

Curt Flood was as crucial to the economic rights of ballplayers as Jackie Robinson was to breaking the color barrier. A three-time All-Star and seven-time winner of the Gold Glove for his defensive prowess in center field, Flood hit more than .300 six times during a 15-year major league career that began in 1956. Twelve of those seasons were spent wearing the uniform of the St. Louis Cardinals. After the 1969 season, the Cardinals attempted to trade Flood, then 31 years of age, to the Philadelphia Phillies, which set in motion his historic challenge of baseball’s infamous “reserve clause.” The reserve clause was that part of the standard player’s contract which bound the player, one year at a time, in perpetuity to the club owning his contract. Flood had no interest in moving to Philadelphia, a city he had always viewed as racist (“the nation’s northernmost southern city”), but more importantly, he objected to being treated as a piece of property and to the restriction of freedom embedded in the reserve clause.

Curt Flood was as crucial to the economic rights of ballplayers as Jackie Robinson was to breaking the color barrier. A three-time All-Star and seven-time winner of the Gold Glove for his defensive prowess in center field, Flood hit more than .300 six times during a 15-year major league career that began in 1956. Twelve of those seasons were spent wearing the uniform of the St. Louis Cardinals. After the 1969 season, the Cardinals attempted to trade Flood, then 31 years of age, to the Philadelphia Phillies, which set in motion his historic challenge of baseball’s infamous “reserve clause.” The reserve clause was that part of the standard player’s contract which bound the player, one year at a time, in perpetuity to the club owning his contract. Flood had no interest in moving to Philadelphia, a city he had always viewed as racist (“the nation’s northernmost southern city”), but more importantly, he objected to being treated as a piece of property and to the restriction of freedom embedded in the reserve clause.

Flood was fully aware of the social relevance of his rebellion against the baseball establishment. Years later, he explained, “I guess you really have to understand who that person, who that Curt Flood was. I’m a child of the sixties, I’m a man of the sixties. During that period of time this country was coming apart at the seams. We were in Southeast Asia. Good men were dying for America and for the Constitution. In the southern part of the United States we were marching for civil rights and Dr. King had been assassinated, and we lost the Kennedys. And to think that merely because I was a professional baseball player, I could ignore what was going on outside the walls of Busch Stadium was truly hypocrisy and now I found that all of those rights that these great Americans were dying for, I didn’t have in my own profession.”

With the backing of the Players Association and with former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg arguing on his behalf, Flood pursued the case known as Flood v. Kuhn (Commissioner Bowie Kuhn) from January 1970 to June 1972 at district, circuit, and Supreme Court levels. Although the Supreme Court ultimately ruled against Flood, upholding baseball’s exemption from antitrust statutes, the case set the stage for the 1975 Messersmith-McNally rulings and the advent of free agency.

The financial and emotional costs to Flood as a result of his unprecedented challenge of the reserve clause were enormous. Flood’s major league career (his 1970 salary would have been $100,000) effectively ended with his legal action, and he traveled to Europe, spending much of his time there painting and writing, attempting to deal with the pain and frustration of being away from the game he loved. In 1970, prior to the Supreme Court decision, Flood published his autobiography, The Way It Is, a riveting book which forcefully outlined his moral and legal objections to baseball’s reserve system. Flood’s impassioned literary account of his life is now considered an essential text in the history of the baseball labor movement.

At the memorial service for Curt Flood, who died of throat cancer in 1997 at the age of 59, dozens of former ballplayers gathered at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Los Angeles to pay tribute to a man whose sacrifice made him not merely a hero, but a martyr. One mourner compared Flood’s social legacy to that of Rosa Parks, while former player Tito Fuentes wondered why the current generation of baseball’s multi-millionaires did not attend the service to pay their respect. “He was a great man,” Fuentes remarked as he passed by Flood’s casket. “I’m sorry that so many of the young players who made millions, who benefited from his fight, are not here. They should be here.”

Former executive director of the Major League Players Association, Marvin Miller, said, “At the time Curt Flood decided to challenge baseball’s reserve clause, he was perhaps the sport’s premier center fielder. And yet he chose to fight an injustice, knowing that even if by some miracle he won, his career as a professional player would be over. At no time did he waver in his commitment and determination. He had experienced something that was inherently unfair and was determined to right the wrong, not so much for himself, but for those who would come after him. Few praised him for this, then or now. There is no Hall of Fame for people like Curt.”

That is, until now . . . . and the Baseball Reliquary is honored to have Curt Flood in its first class of electees to the Shrine of the Eternals.

William Louis Veeck, Jr.

Born 2/9/14, Chicago, Illinois

Died 1/2/86, Chicago, Illinois

A self-proclaimed “hustler,” Bill Veeck, Jr. was the greatest public relations man and promotional genius the game of baseball has ever seen. The son of former Chicago Cubs president Bill Veeck, Sr., he got his start in the baseball business selling peanuts and hot dogs at Wrigley Field and was fond of saying that he was “the only human being ever raised in a ballpark.” Over the course of a fifty-year love affair with baseball, Veeck would own three major league teams and would establish himself as the game’s most incorrigible maverick.

A self-proclaimed “hustler,” Bill Veeck, Jr. was the greatest public relations man and promotional genius the game of baseball has ever seen. The son of former Chicago Cubs president Bill Veeck, Sr., he got his start in the baseball business selling peanuts and hot dogs at Wrigley Field and was fond of saying that he was “the only human being ever raised in a ballpark.” Over the course of a fifty-year love affair with baseball, Veeck would own three major league teams and would establish himself as the game’s most incorrigible maverick.

Upon returning from military duty in World War II, during which he received a severe leg wound that would ultimately require amputation, Veeck bought his first major league team, the Cleveland Indians, in 1946 at the age of 32. Although his reign in Cleveland was a mere three-and-a-half years, neither the Indians nor the game of baseball were quite the same thereafter. In 1947 Veeck hired the American League’s first black player (Larry Doby), and a year later brought Cleveland its first pennant and world championship since 1920, establishing a new major league season attendance record of 2.6 million fans. He introduced fireworks displays after games and signed 42-year-old Negro League pitching legend Satchel Paige to a contract in 1948, making him the oldest rookie ever to play professional baseball. Veeck even staged a night for Joe Earley, after the fan protested that the Indians owner had honored everyone except the average “Joe.”

After selling the Indians, Veeck took on his greatest challenge in 1951: ownership of what he called “a collection of old rags and tags known to baseball historians as the St. Louis Browns.” Veeck operated under the premise that fans should have a good time at the ballpark, even if the home team loses. (And the St. Louis Browns lost often, finishing dead last in the American League in 1951 with a 52-102 record, 46 games out of first place.) Veeck’s most memorable promotion for the Browns was sending 3’7″ midget Eddie Gaedel to the plate, but perhaps even more daring was staging “Grandstand Managers’ Day,” in which the fans determined the team’s actual strategy by holding up large placards marked “YES” on one side and “NO” on the other. Ironically, with the Grandstand Managers deciding whether the team bunted, stole a base, changed pitchers, etc., the Browns broke a four-game losing streak with a 5-3 victory. The fans retired with a 1.000 winning percentage and are still waiting for a visionary owner to hire them again.

Veeck’s final major league team was the Chicago White Sox, which he owned twice, from 1959-1961 and then again from 1976-1980. While at the helm of the Pale Hose, Veeck installed baseball’s first exploding scoreboard at Comiskey Park; introduced the game’s first avant-garde uniform in 1976, consisting of a pullover shirt with a straight bottom to be worn pajama style outside of Bermuda shorts; and orchestrated, with the assistance of his son Mike, the infamous “Disco Demolition Night” in 1979.

Bill Veeck once said that “baseball must be a great game, because the owners haven’t been able to kill it,” a sardonic comment from a man who often infuriated the stuffed shirts in the executive suite. The starched, button-down fraternity of baseball owners (or, as Veeck called them, the “forward-looking fossils who run the game”) viewed his promotions and innovations as undignified “travesties.” Probably the low point of his popularity among fellow owners came in 1972 when he testified on behalf of Curt Flood’s effort to overturn baseball’s reserve clause, which Veeck had always regarded as illegal. (It was not unusual to find Veeck championing liberal and sometimes unpopular causes, both in and out of baseball. Although he had an artificial leg, he participated in the day-long civil rights march in Selma, Alabama in March of 1965, without the use of crutches.)

But as much as his fellow owners abhorred him, Veeck was as passionately respected by his players and by the fans, who found him generous and unpretentious. Larry Doby said he was fortunate to have worked for Veeck and called him “probably the nicest and the greatest man that I ever met. He never showed any prejudice or bigotry or racism within himself. He fought for the little man, the underdog.” Veeck maintained a genuine open-door policy, telling his fans, “You call Comiskey Park (WA4-1000) and ask for Bill Veeck and the switchboard operator isn’t going to ask who you are or what you want; the next voice you hear is going to be mine.”

In his final years Veeck adopted the Chicago Cubs and could often be found sitting, without a shirt, in the bleachers at Wrigley Field, where baseball remained a game played only under the sunlight. Although he carried a lifetime pass in his wallet to any ballpark in the major leagues, he preferred to pay his own way. “I pay for my tickets so I can complain,” he remarked. At Veeck’s funeral in 1986 at the Church of St. Thomas the Apostle in Chicago, it was most appropriate that a lone trumpeter opened the services playing Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man.” That is, after all, precisely how Bill Veeck, Jr. would like to have been remembered.

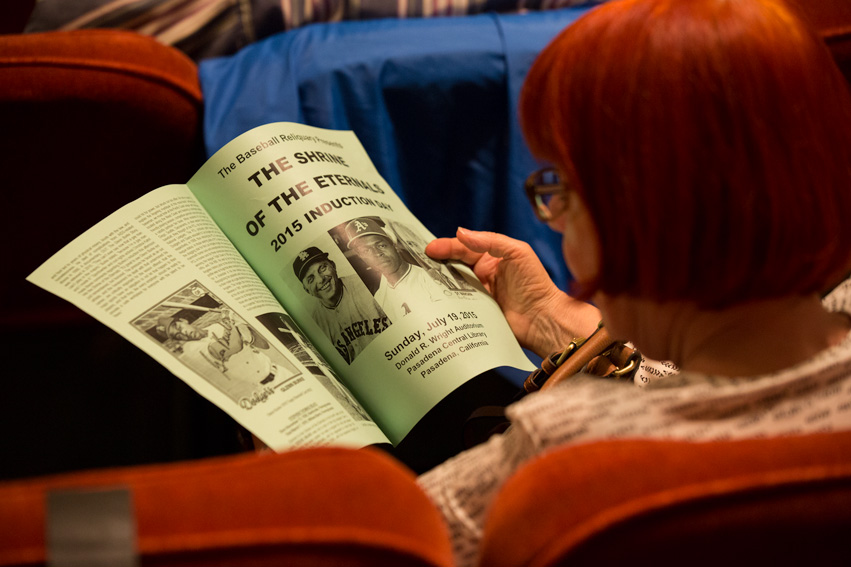

1999 Induction Day

1999 Induction Day Benediction by William Scaff

Member, Board of Directors, The Baseball Reliquary

How does god fit in to baseball?

If you have spent any time with the game of inches

you may eventually ponder this question

How does God fit in to baseball?

Does God manipulate players and situations in order to effect

the outcome of the game?

Is God a fan of a particular team?

Does God even care who wins the World Series?

How does God fit in to baseball?

She makes herself real small

and gets into the cushion cork center where She will be well

protected by the wool and cotton winding and the cowhide cover

and then

She’s ready for a

roller coaster ride.

God wants to FEEL the arc of a curve ball.

God wants to BE a hard slider.

God wants to be clocked at 95 MPH on the radar gun.

God wants to be blistered down the third base line

picking up chalk along the way.

God wants to be bobbled, booted, bunted, balked, blooped,

and, yes,

God wants to be . . .

autographed.

And once you’ve become aware that God is residing inside

the baseball . . .

the highest respect you can give to God

is with one big swing of the bat

and

T H W A C K !

THIS GOD IS G-O-O-O-ONE! ! !