Morris “Moe” Berg

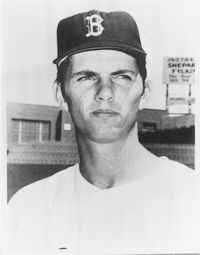

Wedged between Lou Berberet and Augie Bergamo in the Baseball Encyclopedia, Morris “Moe” Berg spent 17 years in professional baseball as a player and coach and was perhaps the most enigmatic and cerebral figure the game has ever known. At least two biographies have attempted to unravel the mysteries surrounding this American original, described by Casey Stengel as “the strangest fellah who ever put on a uniform.” A shadowy figure who had a reputation of appearing and disappearing without warning, Berg was perfectly suited for espionage work. He was also a great storyteller who delighted in embellishing his stories; the difficulties in sorting out fact from fiction in Berg’s life have only enhanced his cult status in some baseball circles.

Wedged between Lou Berberet and Augie Bergamo in the Baseball Encyclopedia, Morris “Moe” Berg spent 17 years in professional baseball as a player and coach and was perhaps the most enigmatic and cerebral figure the game has ever known. At least two biographies have attempted to unravel the mysteries surrounding this American original, described by Casey Stengel as “the strangest fellah who ever put on a uniform.” A shadowy figure who had a reputation of appearing and disappearing without warning, Berg was perfectly suited for espionage work. He was also a great storyteller who delighted in embellishing his stories; the difficulties in sorting out fact from fiction in Berg’s life have only enhanced his cult status in some baseball circles.

Berg was born in New York City on March 2, 1902. It is known that his affinity for baseball as a youth baffled his Russian immigrant family. Despite the objections of a stern father who regarded baseball as a useless American frivolity and never saw his son play, Berg pursued a career as a ballplayer. After graduating from high school with honors, Berg was accepted at Princeton (one of the country’s most WASPish colleges), an extraordinary achievement at that time for a poor Jewish boy. Berg became a distinguished scholar whose intellectual capacity was truly boundless. He was a linguistic prodigy, studying seven languages at Princeton, including Sanskrit. He also excelled athletically and was the star shortstop of the school’s baseball team, which won 18 consecutive games in his senior year.

Upon graduating from Princeton, Berg joined the Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers) as a backup catcher in 1923, and his baseball salary allowed him to continue pursuing his education at the Sorbonne in Paris, where he studied linguistics, and later at Columbia University, where he earned a law degree. Berg played for a succession of major league teams during the next 14 seasons, including the Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and Boston Red Sox. Although he was a strong defensive catcher, Berg was slow of foot and a mediocre hitter, with a .243 lifetime batting average and only six career home runs. In fact, the stock phrase used to describe Berg’s playing ability was that “he could speak a dozen languages but couldn’t hit in any of them.” But his vast knowledge of scholarly subjects ranging from medieval literature to experimental phonetics made him a favorite of sportswriters. Another fellow genius, Casey Stengel, called Berg “as smart a ballplayer that ever came along. It was amazing how he got all that knowledge and used them penetrating words, but he never put on too strong. They all thought he was like me, you know, a bit eccentric.” Berg’s keen understanding of the game was evidenced with the publication of his essay “Pitchers and Catchers” in 1941 in Atlantic Monthly. This lengthy piece on the intricacies and strategies of baseball is still considered a classic of its genre.

In 1934, Berg, perhaps incongruously, was named to an American League all-star team that toured Japan and featured such greats as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx. Berg was idolized by the Japanese because of his mastery of their language and broad understanding of their culture. Unbeknownst to his hosts, however, he was secretly filming Tokyo’s shipyards, industrial complexes, and military installations from the rooftop of a hospital building. The oft-repeated claim that these images were later used in planning General Jimmy Doolittle’s 1942 raids on the Japanese mainland has never been confirmed. In any event, Berg’s daring stunt tested and demonstrated his capacity for invention and steady nerves, which would serve him well when, after leaving baseball, he joined the Office of Strategic Services, which preceded the CIA as America’s first national intelligence agency. Berg would become a highly successful spy during World War II.

Among his many missions on behalf of the OSS was to learn all he could about Adolf Hitler’s atomic bomb project. In December of 1944, Berg, posing as a Swiss physics student, attended a lecture in Zurich by Germany’s foremost atomic physicist, Werner Heisenberg. Carrying a pistol and a lethal cyanide tablet, Berg was ordered to assassinate Heisenberg on the spot if the scientist suggested a Nazi atomic bomb was imminent. Fortunately, the talk focused on basic physics and at a post-lecture dinner party, Berg, whose fluent German covered his identity as an American agent, engaged Heisenberg in an apparently casual conversation. The physicist intimated that Germany’s nuclear effort was lagging behind that of the Allies. Berg immediately cabled Heisenberg’s remarks to OSS headquarters in Washington. President Roosevelt was then briefed on Berg’s report by one of his generals. “Let’s pray Heisenberg is right,” Roosevelt responded. “And, General, my regards to the catcher.” Berg was awarded the Medal of Freedom for his espionage work, but rejected the award “with due respect for the spirit with which it was offered.”

After the war and for the rest of his life, Berg remained an elusive figure. By his own description, he became a “vagabond,” living off the generosity of friends. But he always remained faithful to baseball and regularly attended games. A nurse at the Newark, New Jersey hospital where he died on May 29, 1972 recalled his final words as, “How did the Mets do today?” He left no estate of any kind and his ashes are buried somewhere on Mount Scopus outside of Jerusalem, but the exact site has been forgotten. In his biography of Berg, The Catcher Was a Spy, Nicholas Dawidoff wrote that “the final mystery of Moe Berg’s inscrutable life is that nobody knows where he is.”

William Francis Lee

For 14 years as a left-handed pitcher (1969-1982), ten with Boston and four with Montreal, Bill Lee was anything but a conventional major league ballplayer. His career record was a respectable 119-90, including three consecutive 17-win seasons with the Red Sox (1973-1975) and a 16-win season with the Expos in 1979. He was selected to the American League All-Star squad in 1973 and pitched in the World Series in 1975 against the Cincinnati Reds. But it was Lee’s rebellious spirit and opposition to the conservative baseball establishment that usually rated more attention than his performance on the field. Lee’s coach at the University of Southern California, Rod Dedeaux, said that his pupil did little to dispel the stereotypes about southpaw pitchers: “I always understood everything Casey Stengel said, which sometimes worried me. But I know that all my hours with Casey helped prepare me for Billy Lee.”

For 14 years as a left-handed pitcher (1969-1982), ten with Boston and four with Montreal, Bill Lee was anything but a conventional major league ballplayer. His career record was a respectable 119-90, including three consecutive 17-win seasons with the Red Sox (1973-1975) and a 16-win season with the Expos in 1979. He was selected to the American League All-Star squad in 1973 and pitched in the World Series in 1975 against the Cincinnati Reds. But it was Lee’s rebellious spirit and opposition to the conservative baseball establishment that usually rated more attention than his performance on the field. Lee’s coach at the University of Southern California, Rod Dedeaux, said that his pupil did little to dispel the stereotypes about southpaw pitchers: “I always understood everything Casey Stengel said, which sometimes worried me. But I know that all my hours with Casey helped prepare me for Billy Lee.”

Lee was one of the game’s few counterculture symbols: he talked to animals, championed environmental causes, practiced yoga, ate health foods, sprinkled marijuana on his buckwheat pancakes (an indiscretion for which he was fined $250 by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn), pondered Einstein and Vonnegut, quoted from Mao, and studied Eastern philosophers and mystics. It was in this context that former Red Sox teammate John Kennedy first dubbed him “Spaceman,” a nickname writers thereafter used as shorthand to describe his free spirit. At first irritated by the appellation (preferring to be known as “Earth Man”), Lee would eventually approve of the “Spaceman” moniker. “I realized that it’s the ultimate compliment,” he remarked. “Everybody thinks they’re earthlings but in actuality we’re only here for a brief moment, and the cinder that we’re on is moving as Spaceship Earth, so we’re all space travelers.”

A folk hero to fans (especially to the students, hippies, and radical subculture that adopted Fenway Park in the early ‘70s), Lee was a voice of reason and sanity in a game corrupted by “planet-polluting owners” and the corporate mindset. Although he often crossed swords with management, matching his wits with their authority, Lee, in hindsight, can be viewed not as a rebel but as a “purist” and “traditionalist.” In his freewheeling autobiography, The Wrong Stuff (1984), Lee argued his case: “I hated the D.H. and all the other new wrinkles that had been introduced in an attempt to corrupt the game. I wanted to go back to natural grass, pitchers who hit, Sunday doubleheaders, day games, and the nickel beer. . . . We have to drive these atrocities out of baseball. It will be doing the entire country a great service. Baseball is the belly button of America. If you straighten out the belly button, the rest of the country will follow suit.”

Lee’s belief that ballplayers had an obligation to work for the good of humankind rooted his value system squarely in a socially-conscious, 1960s mentality. And he saw no contradiction in an athlete maintaining a strong competitive desire in concert with humanistic values, addressing this issue directly in the final paragraph of The Wrong Stuff: “If I accomplished anything as a player, I hope it’s that I proved you could exist as a dual personality in the game. I had to pass through the looking glass every time I went out on the field. Away from the ballpark, I tried to care about the earth, and I wasn’t concerned with getting ahead of the ‘other guy.’ On the mound, I was a different person, highly competitive and always out to win. Who I was off the field fed the person I became on it. I had to make the stands I did. To be silent in the face of injustice would have made my life and my pitching meaningless. If I was able to keep my compassion while retaining my competitive senses, then I would judge my career a success. I hope I was able to make more than just a few fans smile, while showing them that the game shouldn’t be taken too seriously. If I am remembered by anyone, I would want it to be as a guy who cared about the planet and the welfare of his fellow man. And who would take you out at second if the game was on the line.”

When Bill Lee was given his walking papers by the Montreal Expos in 1982 (which he appropriately signed “Bill Lee, Earth ‘82”), only the chapter of his life dealing with major league baseball was closed. He still plays baseball whenever and wherever he can, participating in fantasy camps and organized leagues or competing in whatever sandlot games he can get into. “I just don’t want to look fat when they bury me,” adds Lee. Baseball’s version of Peter Pan, Lee is scheduled to pitch a doubleheader in Portland, Maine the day before his induction into the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals.

A resident of Vermont, Lee continues to break barriers and blaze new grounds, having recently barnstormed Cuba with a team of American old-timers competing against senior Cuban players.

Pam Postema

Albert Kilchesty, the Baseball Reliquary’s Archivist/Historian, has observed, “Many writers have gushed profusely about baseball’s role as a social mirror, reflecting all that is noble and wholesome about American life. Baseball is a mirror of American life, but it reflects more frequently all that is wrong with America, not what is right. America’s struggle with issues of ‘difference’ — race, class, gender, sexual orientation — are all reflected glaringly in the great American pastime. While one could cite any number of instances in which baseball has responded to perceived ‘threats’ to its purity by blackballing alleged ‘offenders,’ the case of Pam Postema, an umpire, is especially appalling.”

Albert Kilchesty, the Baseball Reliquary’s Archivist/Historian, has observed, “Many writers have gushed profusely about baseball’s role as a social mirror, reflecting all that is noble and wholesome about American life. Baseball is a mirror of American life, but it reflects more frequently all that is wrong with America, not what is right. America’s struggle with issues of ‘difference’ — race, class, gender, sexual orientation — are all reflected glaringly in the great American pastime. While one could cite any number of instances in which baseball has responded to perceived ‘threats’ to its purity by blackballing alleged ‘offenders,’ the case of Pam Postema, an umpire, is especially appalling.”

Following in the footsteps of Bernice Gera and Christine Wren, the first two women to go through umpiring school and work briefly in the minor leagues, Pam Postema was one of 130 students who enrolled in the 1977 winter session of the Al Somers Umpire School in Daytona Beach, Florida. Describing the Somers school as “an umpire’s version of boot camp,” Postema finished high in her class and began her professional career in the same year at the rookie-level Gulf Coast League. She spent the next 13 years steadily progressing through the ranks of minor league umpiring, by far the longest tenure of any woman in an on-field capacity in major professional sports. Following stops at the Class-A Florida State League and the Class-AA Texas League, Postema arrived at the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in 1983. She was an excellent arbiter and a hard worker, extremely dedicated to her profession. After watching many of her male counterparts, often possessing less experience than she, promoted to the big leagues, Postema at last seemed assured of a major league umpiring slot. But that promotion never came, as the Lords of Baseball refused to allow her entrance to their good ol’ boy network. After six years at the highest rung of minor league baseball, Postema was released from her contract by the Triple-A Alliance in 1989, thus ending her dream of umpiring in the major leagues.

Postema faced seemingly insurmountable roadblocks along the way, from low pay to poor working conditions to a constant battle for respect from players, managers, and colleagues. She had hoped everyone would grow bored with the novelty of a woman umpire, and she would slip into the major leagues unnoticed. But after Bob Knepper’s Neanderthal comments following a 1988 spring training game, Postema realized that no matter how competent she was as an arbiter, she would never crack baseball’s all-male domain. After praising her work behind the plate, the Astros pitcher launched into a chauvinistic tirade: “I just don’t think a woman should be an umpire. There are certain things a woman shouldn’t be and an umpire is one of them. It’s a physical thing. God created women to be feminine. I don’t think they should be competing with men. It has nothing to do with her ability. I don’t think women should be in any position of leadership. I don’t think they should be presidents or politicians. I think women were created not in an inferior position, but in a role of submission to men. You can be a woman umpire if you want, but that doesn’t mean it’s right. You can be a homosexual if you want, but that doesn’t mean that’s right either.”

Postema eventually filed a sexual discrimination lawsuit against major league baseball in Federal court, which was later settled. In 1992, while working as a truck driver for Federal Express in California, she published her no-holds-barred autobiography, You’ve Got to Have Balls to Make It in This League. On major league baseball’s determination to keep their field of dreams a male privilege, Postema wrote, “Almost all of the people in the baseball community don’t want anyone interrupting their little male-dominated way of life. They want big, fat male umpires. They want those macho, tobacco-chewing, sleazy sort of borderline alcoholics. If you fit their idea of what a good umpire is, then you’re fine. And isn’t that the way society is? Nobody wants any glitches. If somebody is a nonconformist like me or, say, Dave Pallone, then we get shown the door. It’s hard to accept. And I’ll never understand why it’s easier for a female to become an astronaut or cop or fire fighter or soldier or Supreme Court justice than it is to become a major league umpire.”

In the concluding chapter of her book, Postema candidly addresses the fallacy of her belief that as long as she did her job, it didn’t matter what sex she was. Her 13-year experience proved to her that the men who run baseball could care less about equal rights. Postema contends she made a strategic mistake in downplaying her feminist beliefs so as not to alienate the baseball establishment, preferring to fight the battle on her own without the help of any women’s organizations that she could have relied on for support. In hindsight, she would have trumpeted her feminist beliefs, drawing attention to herself and to the plight of women, rather than being the “respectful little soldier.”

Postema is currently a factory worker in her home state of Ohio. Over a decade after leaving professional umpiring, she still awaits the day that baseball’s last barrier will be broken.

2000 Induction Day – July 16, 2000, Pasadena, California

On Sunday, July 16, 2000, over 150 people filled the Donald R. Wright Auditorium in the Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, for the 2000 Induction Day ceremony of the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals.

The festivities began at 2:30 PM (Pacific Standard Time) with a ceremonial bell ringing in tribute to the late, great Hilda Chester, who for thirty years sat in the bleachers at Ebbets Field as the unofficial mascot of the Brooklyn Dodgers, clanging her cowbells and banging her frying pans and iron ladles. The Reliquary’s founder and Executive Director, Terry Cannon, who also served as Master of Ceremonies for the day’s festivities, called Hilda “perhaps the most famous fan and percussionist in baseball history” and remarked that the bell ringing has now become tradition as the call-to-order for the Induction Day ceremony. Cannon added: “Hilda’s voice, which was described as being like that of a fish peddler, could be heard throughout the ballpark, and when someone would dare to criticize one of her beloved Dodgers — especially her personal favorite, Leo Durocher — she could be heard to shout, ‘Eatcha heart out, ya bum!’”

Keynote Addresses

Following the singing of the National Anthem by jazz vocalist Leontine Guilliard and a few welcoming remarks on behalf of the City of Pasadena by Mayor Bill Bogaard, the first of two keynote addresses was delivered by Tony Salin. A San Francisco-based oral historian and author of Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: One Fan’s Search for the Game’s Most Interesting Overlooked Players, Salin encouraged the audience to read some of the many books written about little-known ballplayers of the past. In a speech peppered with anecdotes about players like Art Pennington, Pete Gray, Steve Dalkowski, and Len Koenecke, Salin commented, “When I wrote Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, I had a goal in mind. I was hoping to get more fans to realize how enjoyable it is to read about former players. There’s drama, humor, and lessons to be learned by readers of all ages. One thing I’ve learned, there is a limitless amount of wonderful baseball stories. You’ll never run out.”

Salin remarked that one of the things he likes best about the Baseball Reliquary is that it “helps educate the public about little-known players who should be better known” and cited Jackie Price as one such player that he would like to see elected to the Shrine of the Eternals some day. Price was a baseball entertainer whose miraculous stunts included taking batting practice for over fifteen minutes at a time while being suspended upside-down from his ankles. He could also hold three baseballs in his throwing hand and toss them in one motion to three different players stationed around the infield. Salin recalled that another former player, Dick Adams, who worked with Price one day at a minor league park, told him that “Price could put the knob end of the bat through the fly of his pants and hit a pitched ball,” a comment which drew considerable laughter from the audience.

The second keynote address was made by Tomas Benitez, an arts professional for over twenty years who has worked with a number of community groups in East Los Angeles, including Plaza de la Raza, the Bilingual Foundation of the Arts, and Self-Help Graphics & Art, which he currently serves as director. Benitez spoke about growing up playing baseball in the sandlots of East Los Angeles: “My first team would be a multicultural dream of Central Casting. We had a couple of Jews, a couple Mexicans, a couple of Italians, Chuck the black kid, and a girl. We made our bases out of contraband cardboard, and we played from the time it was daylight until the time it stopped being daylight. Later on, we added the Sanchez sisters and Eugene and Patsy. Eugene threw like a girl and Patsy hit like a boy, so it was a good tradeoff.” He talked about how the game of baseball was one of the important elements that allowed for the “Americanization” of young Chicanos who grew up in Los Angeles during the 1950s and ‘60s, and reminisced about seeing Wally Moon hitting “Moonshots” over the left-field screen at the Coliseum.

Tomas Benitez delivers keynote address at the Induction Day ceremony of the Shrine of the Eternals.

Benitez also addressed the subject of the corollary between baseball and art and how the game has been important to artists because of its timelessness, its unique sense of space, and its imperfections. And on the subject of the Baseball Reliquary, he noted: “We here at the Reliquary know our place. We are fans. We are not informed, experienced ballplayers. We know our place, and we also know that we know our place a little better than most fans, don’t we? There is an arrogance to us, and it’s a wonderful arrogance that’s underscored by passion. How else can we relish wanting to own Dick Stuart’s glove rather than Gil Hodges’? And yet here is a place that has provided to us a cachet — a place where people within the arts can also relish in their love, in their special knowledge of understanding this game.”

Benitez thanked this year’s and last year’s inductees and concluded by saying, “But this museum is really about us. It’s a museum for us — the fans that know, that care a little bit more, that enjoy the uniqueness and the character, the things that have been distinguished in our own lives as artists. And leave it to a group of artists to create a place that is fitting for a group of immortals who otherwise don’t fit in. And, therefore, leave it to the joy of those visionaries to create this place which is etched in the profile of their own niche.”

Moe Berg

The formal induction proceedings began with Moe Berg. Prior to his introduction of Jon Blank, who was accepting Berg’s induction, Albert Kilchesty, the Reliquary’s Archivist/Historian, noted that in last year’s keynote address, “I spoke at some length about the difference between baseball fact and baseball fiction and the precarious position that the Baseball Reliquary occupies between these two poles. It isn’t at all surprising to me, then, that I have been asked to introduce our first inductee this year. After all, Morris ‘Moe’ Berg made a career out of blurring the distinctions between fact and fiction in his personal life. Additionally, his wide ranging interests, his esoteric and encyclopedic knowledge, and his unlikely career as a catcher and a spy make Berg, at least in my opinion, the quintessential Reliquarian. To paraphrase another writer speaking about another American original, if Moe Berg hadn’t really existed, it would be necessary for us to invent him. Thankfully Moe Berg did exist, for I doubt that even the most imaginative and talented among us would be able to conjure a character as inscrutable, enigmatic, and contradictory as Berg. In fact, being asked to introduce Moe Berg, I feel as though I have been asked to explain the Sphinx or to describe the meaning of Mona Lisa’s smile in less than two minutes.

“In the figure of Moe Berg, we find a very comfortable and near perfect fusion of what we artist types like to call high and low culture. He could converse as easily with diplomats, scholars, and nuclear physicists as well as with unschooled teammates, hack sportswriters, and fans. He could handle a fastball from Lefty Grove as well as a difficult assignment from OSS chief ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan. There is no either/or quality to Moe Berg’s life, nothing that indicates that he had to pursue one vocation rather than another. He was not afflicted with the disease of the specialist. Berg was a scholar and a lawyer; a linguist and a radio show personality; a convivial conversationalist and an utter cipher; an intensely private man and a citizen of the world; a third-string catcher and, if you choose to believe all the reports, a first-rate atomic spy. He is the only person to have both an entry in the Baseball Encyclopedia and the Encyclopedia of Espionage.”

Jon Blank accepts the induction of Moe Berg into the Shrine of the Eternals.

After providing some biographical details pertaining to Berg’s life, Kilchesty concluded by saying, “On his deathbed in 1972, Berg is said to have asked his nurse, ‘How did the Mets do today?’ These are the purported last words of a man whose intelligence, audacity, knowledge, and multiple careers and talents would seem at odds with the grand old game’s simplicity. Yet Moe Berg nevertheless managed to maintain, to the befuddlement of many, a profound interest in the game, its rituals, and its personalities until the moment of his death. The Baseball Reliquary is pleased to recognize the singular contributions that Mr. Morris ‘Moe’ Berg made to American culture by inducting him into the Shrine of the Eternals’ class of 2000.”

Berg’s induction was accepted by Jon Blank, Director of the Jewish Baseball Western Wall of Fame, a peripatetic museum dedicated to preserving the memory of Jewish major league players and instructing the public about the contributions those players have made to American culture. Blank provided additional biographical insight into Berg’s extraordinary life. He considered it a great tribute to Berg that there were those who urged him to think seriously about the position of Supreme Court Justice, while others felt he would make an excellent Commissioner of Baseball. There have been seven books published on the subject of Moe Berg, yet, as Blank remarked, “The question which lingers to this day is what motivated him? In 1940, while Hitler was consuming Europe and burning books, Moe made a speech at a Boston book fair. He said what Montaigne wrote about Paris describes how he feels about America: ‘I love her so tenderly that even her spots, her blemishes, are dear unto me.’”

At the conclusion of his acceptance speech, Blank presented the Baseball Reliquary with a copy of Moe Berg’s declassified OSS file, obtained from the CIA and consisting of several hundred pages of documents.

Bill Lee

Ron Shelton introduces Bill Lee at the Induction Day ceremony of the Shrine of the Eternals.

The second inductee, Bill Lee, was introduced by filmmaker Ron Shelton, whose credits include Bull Durham, Cobb, White Men Can’t Jump, Tin Cup, and Play It to The Bone, among others. Shelton, who played minor league ball in the Baltimore Orioles farm system from 1967 to 1971, spoke about growing up straddling the seemingly disparate cultures of sports and radical politics: “During the ‘60s and ‘70s when I played high school and college baseball in Southern California and began my professional career, I discovered I had to live in two different worlds and step back and forth between those worlds as gracefully as possible. One was the world of baseball, of sports and competition, of discipline and preparation for the sheer joy of men playing boys’ games. It was a gift to be able to make your living playing a game, traveling around America by bus with your peers, and being nervous eight months a year having to perform every night, rarely with a day off. Baseball got me a college education, taught me how to read and do math. I could figure out my batting average while rounding first at the age of eight. It taught me all the things that matter: the long season, the need to take your cuts, the hope of waiting till next year. Every cliché in baseball is a religious truth.

“Then there was the world of politics and social activism and literature and protest and, well . . . all of the things that made the ‘60s great. This was a world you generally didn’t discuss with your baseball comrades; in fact, you wouldn’t say comrade with a fellow baseball player. And when you tried to discuss baseball with your political colleagues, they invariably labeled you a reactionary dilettante who was a puppet symbol of free market capitalism with all its ills. So I sort of couldn’t figure out what my peer group was. In fact, for decades I felt part of an unidentified political party. It’s actually sort of a part conservative social values and democratically socialistic one, except when it’s not, and then it is a party of liberal social values and free market political ones. You get the point — it’s hard to find someone to vote for. There were few public figures during this time who stood for this marriage of values. Bill Lee was one of them. This is a marriage that seemed to make perfect sense to me: playing baseball and marching against the war in Vietnam. There were many people who had trouble with that combination. And as more and more people reject the simplistic platforms of our two major political parties, Bill Lee’s organic mixture of social and political values feels more and more appropriate.”

Bill Lee accepts his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals.

Shelton then let Bill Lee be his own introduction, by reading a selection of Lee’s humorous and thought- provoking quotes, several of which were excerpted from the pitcher’s autobiography, The Wrong Stuff. Shelton joked, “Of course, this wouldn’t be the first time I’ve quoted Bill. I stole at least one of his lines for Bull Durham — the one where Crash Davis goes to the mound to lecture his pitcher Nuke Laloosh that he’s throwing too hard: ‘Quit trying to strike everybody out. It’s fascist. Throw some ground balls. It’s more democratic.’ There you are folks, politics and baseball again.”

Shelton concluded his remarks by emphasizing that with all the interest in Bill Lee’s off-the-field activities, we should not forget that he was an exceptional athlete: “There’s one more thing I want to let the record show. I believe in statistics. By the way, a great fielding .243 catcher [Moe Berg] would make about five million a year today. Bill Lee won 119 games in his 14-year major league career. Very few pitchers have won that many games. He pitched on pennant winners, pennant contenders, and in the World Series. His lifetime earned run average was 3.62, an ERA which today is worth about seven million dollars a year. Let it be known that Bill Lee pitched a game last night in Maine, and might have pitched a doubleheader, but he had a ‘red eye’ he wanted to catch. So ladies and gentlemen, the winning pitcher from last night’s Red Sox Legends victory over the Brunswick Police Department, Bill Lee.”

Lee came to the podium still wearing his baseball uniform from the previous night. His acceptance speech was, as might be expected, unconventional. Lee’s monologue, nearly thirty minutes in duration, ran the gamut from political and social commentary to baseball coaching methodologies to stand-up comedy, and he kept the audience laughing throughout. Commenting on everybody from Billy Martin and George Steinbrenner to Don Zimmer and Ted Kaczinski, Lee saved his most acerbic barbs for the Boston Red Sox, his former employer: “People want to know why I haven’t been nominated for the Red Sox Hall of Fame. I work for a group called Save Fenway Park. I’m costing the Red Sox 382 million dollars in taxpayers’ money. The only way I’m going in is posthumously. And if I go in, I want to go in face down so they can kiss my ass. You can see how I got in trouble. I’m bad. My dad said if you’re gonna go anywhere, ask questions. Question authority. He really didn’t mean that and he wished he had never said it.”

Lee ridiculed former batterymate Carlton Fisk, who would be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame the following week: “He was a great guy who’s turned into a surly son-of-a-bitch. He was nasty. He was a catcher. All catchers are nasty. It’s like the guy said, Will Rogers never met a man he didn’t like. He never met Jerry Grote. Catchers are like that. But every ballplayer’s life is a game of getting knocked down. You get hit but you get patched back together. [Lee pulls his shirt down over his shoulder to show the audience a scar from a 1976 brawl at Yankee Stadium.] I’ve had my teeth knocked out six times. You know what Stan Williams said? ‘You don’t play with your face, tiger.’”

He spoke admiringly of Rod Dedeaux and Annabelle Lee, who were in the audience. Lee called himself a disciple of Dedeaux, his baseball coach at the University of Southern California, and said his aunt, Annabelle, who pitched in the All-American Girls Baseball League, taught him how to throw a screwball. He also suggested that one of the reasons major league pitching is so poor today is because “it’s taught by guys like Joe Kerrigan [Red Sox pitching coach], who never threw nine innings in his life.” Lee argued that pitching mechanics are screwed up because coaches no longer teach pitchers to wind up properly and, with a nod of the cap to Buckminster Fuller’s philosophy, cautioned baseball that “overspecialization breeds extinction.”

Finally, Lee acknowledged a few organizations that he feels are attempting to bring sanity to the game: “It’s the Baseball Reliquary, SABR [Society for American Baseball Research], the MSBL [Men’s Senior Baseball League], the Roy Hobbs Baseball League — these are all people that love baseball and tolerate professional baseball. Because it’s an addiction that we can’t get rid of. But the game is supposed to be played on nice fields, in flannels, with wooden bats,no designated hitter. It’s supposed to be played on afternoons with your father and grandfather. . . . And how come Bill Klem didn’t get a vote? I just thought of that. It was a bad year for umpires. I guess Pam must have taken them all.”

Pam Postema

Pam Postema accepts her induction into the Shrine of the Eternals.

The day’s third and final inductee, Pam Postema, was introduced by Susan Braig, a member of the Board of Directors of the Baseball Reliquary. Braig began, “To paraphrase George Bernard Shaw, there are two great disappointments in a person’s lifetime: the dream that never comes true, and the dream that does. So, in each of our fields of dreams, the sweetest satisfaction comes from the milestones we achieve along the way. For Pam Postema, who persevered with the utmost professionalism during a 13-year marathon of tobacco spit and snide remarks, the journey to the outskirts of major league baseball was rich with milestones.”

After recounting Postema’s achievements, Braig added, “But as much as this is a testament to Pam’s exemplary performance and commitment, it is also a disgraceful commentary of the sexism and shortsightedness in professional baseball’s Hall of Shame. Women have become astronauts, prime ministers, surgeons, police officers, Supreme Court Justices, and even professional basketball and soccer referees. But major league baseball, even in this new millennium, continues to let untapped talent slip away. If Pam had been a man instead of a woman, she would have gotten a major league contract by 1988, if not sooner!”

Speaking on behalf of the Board of Directors, Braig said that the Baseball Reliquary was “delighted, in this new millennium, to turn over a new leaf in baseball by electing Pam Postema as the first woman to be inducted into the Shrine of the Eternals. We present Pam with this award with two main intentions: to further ensure Pam’s place in the history books for her amazing accomplishments in spite of the most uncomfortable obstacles; and to open the door a little farther for future generations of women who aspire to a professional baseball career.”

Postema, who earlier in the day donated to the Reliquary her National League umpire’s shirt which she wore while calling spring training games in 1988, delivered a very moving acceptance speech: “Twenty-three years ago I probably became an umpire because someone told me I couldn’t. And for 13 years I endured the great calls, the not-so-great calls, the ‘she’s a major league umpire’ opinion, the ‘she should be home cooking’ sentiment. I think umpiring mirrors life: some days you can’t do anything wrong and other days, well . . . you’d like a hole to crawl in. So for 13 years I had the greatest highs and the greatest lows, and I don’t regret a single minute of it. I don’t know, maybe I could’ve been the greatest umpire in the big leagues, or maybe I would’ve been the worst. But it’s all conjecture now anyway, because it didn’t happen.”

On the subject of will there ever be a woman in the major leagues, Postema offered this opinion: “The world is changing constantly, everything is moving, growing, learning. That’s what life is. And baseball will eventually grow and change. There will be women umpires and women ballplayers, too, in fact. There is no doubt in my mind. It may take a while, but it will happen.” Postema then brought the crowd to laughter with her reflection that “It’s been 11 years since my umpire career ended, but there’s some things from baseball that I still cling to. I still say ‘fuck’ way too much. But for 13 years it was the most prevailing word in my vocabulary.”

Postema concluded: “I want to say I’m really honored to be inducted in your Shrine of the Eternals. I love what this organization is all about. I’ve been called ‘horseshit’ or ‘the greatest’ so much in my career that I don’t go by accolades anymore. But this organization realizes and recognizes my contribution to baseball. We just can’t name what it is. Just maybe I was there — an aberration, an anomaly, an oddity. I was no gimmick.” Postema left the podium and stage to a standing ovation.

Conclusion

The 2000 Induction Day ceremony ended with a whimsical benediction by Chef Guillaume (a.k.a. William Scaff). The chef announced that what was to follow was “either a tribute to Ogden Nash or an apology.” Then he proceeded to read his poem entitled “Line-up for Today: An ABC of Baseball 2000,” an updated version of Nash’s “Line-up for Yesterday: An ABC of Baseball Immortals,” which originally appeared in Sport magazine in 1949 and has been reprinted in numerous anthologies over the years.

While the audience enjoyed refreshments and talked informally with the new inductees, Anne Oncken performed a sampling of baseball songs on the piano. Her presentation included music written between 1874 and 1965. A few of the titles featured were “Cubs on Parade” (1907), “Let’s Get the Umpire’s Goat” (1909), “The Marquard Glide” (1912), “Jake! Jake! (The Yiddisha Ball Player)” (1913), “I Love Mickey” (1956), and “Meet the Mets” (1961).

(Induction Day photographs courtesy of Larry Goren)