Jim Bouton

Born on March 8, 1939 in Newark, New Jersey, Jim Bouton was a major league pitcher of some distinction, whose fierce competitive nature earned him the nickname “Bulldog.” He followed his 7-7 rookie campaign with the New York Yankees in 1962 by posting marks of 21-7 in 1963 and 18-13 in 1964, including two World Series victories over the St. Louis Cardinals. Bouton came up with a sore arm in 1965 and, with his fastball gone, won only nine games in the next four seasons with the Bronx Bombers, before being shipped off to that baseball Siberia in Seattle, Washington. While attempting to resurrect his career in 1969 as a knuckleball pitcher with the Seattle Pilots and Houston Astros, Bouton began writing a diary during the season on notebook paper, hotel stationery, popcorn boxes, ticket stubs, coasters, and anything else that was handy. The end result, Ball Four, published in 1970, became arguably the most influential baseball book ever written, and one which changed the face of sportswriting and our conception of what it means to be a professional athlete. Prior to its publication, baseball books had attempted to provide good examples and tell inspiring, if not always truthful, stories; Ball Four was the stick of dynamite that blasted ballplayers off their pedestals, showing them not as sacrosanct and heroic figures but as flawed and often inglorious men. Igniting a firestorm of controversy, Bouton was called a Judas and a Benedict Arnold for having violated the “sanctity of the clubhouse.” The baseball establishment was outraged by the book’s candid depiction of the sex-obsessed lives of major league players, the stinginess and stipidity of ownership and management, and the intolerance to nonconformists such as Bouton himself (who was distrusted by teammates for his outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War, his strong union stance in the locker room, and his penchant for reading books in the back of the bus). Fearful that Ball Four would damage baseball’s “image,” Commissioner Bowie Kuhn tried to suppress it, only ensuring its commercial success. Although its startling revelations initially overshadowed the book’s brilliance as a document of a highly transformative period in baseball history, Ball Four has, in the three decades since its publication, assumed its proper place in the literature of baseball. It was even anointed in 1995 by the New York Public Library as one of its “Books of the Century,” the only sports book so honored. Bouton would eventually pen a sequel to Ball Four called I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, and even tried his hand at baseball fiction in 1994 by co-writing Strike Zone with Eliot Asinof. Bouton has explored his many interests over the years, including work as a sportscaster, an actor (in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, he played the hitman Terry Lennox, who gets “plugged” at the film’s end by Elliott Gould), an entrepreneur (inventor of shredded bubble gum and vanity trading cards), and most recently, as a motivational speaker. Written by Terry Cannon

Born on March 8, 1939 in Newark, New Jersey, Jim Bouton was a major league pitcher of some distinction, whose fierce competitive nature earned him the nickname “Bulldog.” He followed his 7-7 rookie campaign with the New York Yankees in 1962 by posting marks of 21-7 in 1963 and 18-13 in 1964, including two World Series victories over the St. Louis Cardinals. Bouton came up with a sore arm in 1965 and, with his fastball gone, won only nine games in the next four seasons with the Bronx Bombers, before being shipped off to that baseball Siberia in Seattle, Washington. While attempting to resurrect his career in 1969 as a knuckleball pitcher with the Seattle Pilots and Houston Astros, Bouton began writing a diary during the season on notebook paper, hotel stationery, popcorn boxes, ticket stubs, coasters, and anything else that was handy. The end result, Ball Four, published in 1970, became arguably the most influential baseball book ever written, and one which changed the face of sportswriting and our conception of what it means to be a professional athlete. Prior to its publication, baseball books had attempted to provide good examples and tell inspiring, if not always truthful, stories; Ball Four was the stick of dynamite that blasted ballplayers off their pedestals, showing them not as sacrosanct and heroic figures but as flawed and often inglorious men. Igniting a firestorm of controversy, Bouton was called a Judas and a Benedict Arnold for having violated the “sanctity of the clubhouse.” The baseball establishment was outraged by the book’s candid depiction of the sex-obsessed lives of major league players, the stinginess and stipidity of ownership and management, and the intolerance to nonconformists such as Bouton himself (who was distrusted by teammates for his outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War, his strong union stance in the locker room, and his penchant for reading books in the back of the bus). Fearful that Ball Four would damage baseball’s “image,” Commissioner Bowie Kuhn tried to suppress it, only ensuring its commercial success. Although its startling revelations initially overshadowed the book’s brilliance as a document of a highly transformative period in baseball history, Ball Four has, in the three decades since its publication, assumed its proper place in the literature of baseball. It was even anointed in 1995 by the New York Public Library as one of its “Books of the Century,” the only sports book so honored. Bouton would eventually pen a sequel to Ball Four called I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, and even tried his hand at baseball fiction in 1994 by co-writing Strike Zone with Eliot Asinof. Bouton has explored his many interests over the years, including work as a sportscaster, an actor (in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, he played the hitman Terry Lennox, who gets “plugged” at the film’s end by Elliott Gould), an entrepreneur (inventor of shredded bubble gum and vanity trading cards), and most recently, as a motivational speaker. Written by Terry Cannon

Satchel Paige

Folk-philosopher and self-proclaimed “World’s Greatest Pitcher,” the irrepressible Satchel Paige (1906-1982) delighted both black and white baseball fans throughout North America with his pitching artistry and fancy phraseology during a career that spanned over thirty years. Paige inked his first professional contract with the Negro League Chattanooga Lookouts in 1925. Over the next twenty-three seasons, Paige became one of the top drawing cards in Negro League baseball, pitching for powerhouse squads such as the Birmingham Black Barons, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the Kansas City Monarchs. His wide array of pitches (each bearing a distinctive Paige nickname: the “bat dodger pitch,” the “two-hump blooper,” the “hurry-up ball”) and mound artistry baffled opposing batsmen. Paige also plied his craft against white major leaguers during various barnstorming stints with the Satchel Paige All-Stars. Nearly all major leaguers agreed that, were it not for segregation, Paige would be a perennial all-star in the majors. In 1948, maverick owner Bill Veeck signed Paige to a contract with the Cleveland Indians. Paige’s 6-1 record, attained largely in relief, helped propel the Indians to a World Series championship, their last in the 20th century. Paige pitched briefly in the majors — culminating in a cameo appearance with the Kansas City A’s in 1965 — compiling a lifetime 28-31 record and a 3.29 ERA. Of the several books written by and about Paige, the most entertaining is his second autobiography, written with David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (1962). Satch almost did. Written by Albert Kilchesty

Folk-philosopher and self-proclaimed “World’s Greatest Pitcher,” the irrepressible Satchel Paige (1906-1982) delighted both black and white baseball fans throughout North America with his pitching artistry and fancy phraseology during a career that spanned over thirty years. Paige inked his first professional contract with the Negro League Chattanooga Lookouts in 1925. Over the next twenty-three seasons, Paige became one of the top drawing cards in Negro League baseball, pitching for powerhouse squads such as the Birmingham Black Barons, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the Kansas City Monarchs. His wide array of pitches (each bearing a distinctive Paige nickname: the “bat dodger pitch,” the “two-hump blooper,” the “hurry-up ball”) and mound artistry baffled opposing batsmen. Paige also plied his craft against white major leaguers during various barnstorming stints with the Satchel Paige All-Stars. Nearly all major leaguers agreed that, were it not for segregation, Paige would be a perennial all-star in the majors. In 1948, maverick owner Bill Veeck signed Paige to a contract with the Cleveland Indians. Paige’s 6-1 record, attained largely in relief, helped propel the Indians to a World Series championship, their last in the 20th century. Paige pitched briefly in the majors — culminating in a cameo appearance with the Kansas City A’s in 1965 — compiling a lifetime 28-31 record and a 3.29 ERA. Of the several books written by and about Paige, the most entertaining is his second autobiography, written with David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (1962). Satch almost did. Written by Albert Kilchesty

Jimmy Piersall

“Probably the best thing that ever happened to me was going nuts. Whoever heard of Jimmy Piersall, until that happened?

— Jimmy Piersall, The Truth Hurts

Thanks to Anthony Perkins’ portrayal of Jimmy Piersall in the film Fear Strikes Out (1957), quite a few people, many of them not baseball fans, came to know of Piersall. The brash, high-strung rookie outfielder made a splash with the Boston Red Sox in the early 1950s, but was sent down to the minors after suffering a mental breakdown. Americans during the Eisenhower era weren’t very sympathetic to fellow citizens suffering from mental disorders and, after Piersall’s recovery and return to the Red Sox, baseball fans in opposing cities made his life hell. Largely unfazed by their jibes and taunts, Piersall went six-for-six in his first game back, and subsequently fashioned a very respectable 17-year big league career, ending up with career marks of .272 and 104 HRs (he celebrated his 100th by trotting around the bases backwards, much to the dismay of his manager). He was cited by no less an authority than Casey Stengel as a better defensive outfielder than the incomparable DiMaggio. But perhaps Piersall’s greatest contribution to baseball lay in his insistence that the game should be fun to play. After his recovery, Piersall consistently displayed a keen wit, a (questionable) sense of humor, and a zany joie de vivre that some writers and fans loved, but which weren’t always appreciated in the clubhouse and front office. After his retirement in 1967, Piersall worked at a number of baseball-related jobs, most notably as a radio broadcaster with the White Sox. However, Jimmy’s broadcasting career was short-circuited after repeated on-air criticisms of players, the manager, and the team-owner’s wife. Written by Albert Kilchesty

Thanks to Anthony Perkins’ portrayal of Jimmy Piersall in the film Fear Strikes Out (1957), quite a few people, many of them not baseball fans, came to know of Piersall. The brash, high-strung rookie outfielder made a splash with the Boston Red Sox in the early 1950s, but was sent down to the minors after suffering a mental breakdown. Americans during the Eisenhower era weren’t very sympathetic to fellow citizens suffering from mental disorders and, after Piersall’s recovery and return to the Red Sox, baseball fans in opposing cities made his life hell. Largely unfazed by their jibes and taunts, Piersall went six-for-six in his first game back, and subsequently fashioned a very respectable 17-year big league career, ending up with career marks of .272 and 104 HRs (he celebrated his 100th by trotting around the bases backwards, much to the dismay of his manager). He was cited by no less an authority than Casey Stengel as a better defensive outfielder than the incomparable DiMaggio. But perhaps Piersall’s greatest contribution to baseball lay in his insistence that the game should be fun to play. After his recovery, Piersall consistently displayed a keen wit, a (questionable) sense of humor, and a zany joie de vivre that some writers and fans loved, but which weren’t always appreciated in the clubhouse and front office. After his retirement in 1967, Piersall worked at a number of baseball-related jobs, most notably as a radio broadcaster with the White Sox. However, Jimmy’s broadcasting career was short-circuited after repeated on-air criticisms of players, the manager, and the team-owner’s wife. Written by Albert Kilchesty

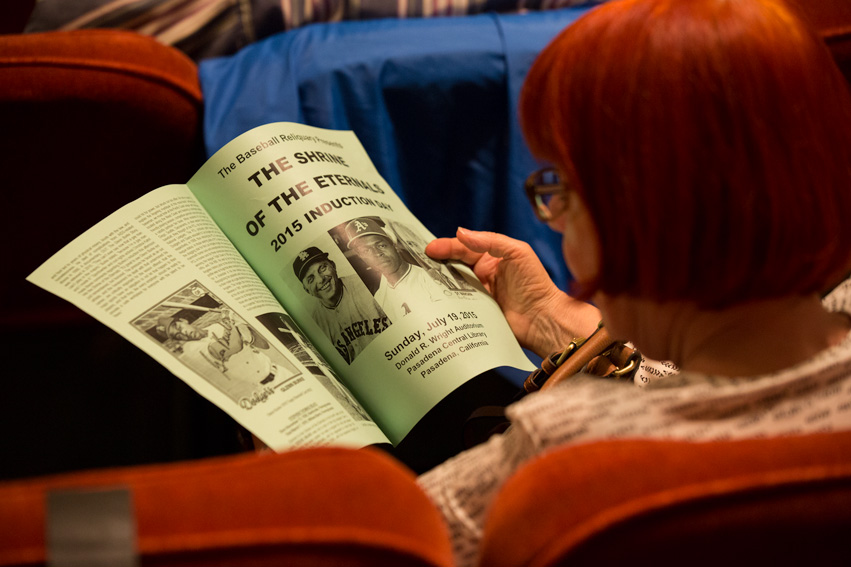

2001 Induction Day – July 29, 2001, Pasadena, California

On Sunday, July 29, 2001, a capacity crowd of nearly 175 people filled the Donald R. Wright Auditorium in the Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California, for the 2001 Induction Day ceremony of the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals. The festivities began at 2:00 PM (Pacific Standard Time) with the traditional ceremonial bell ringing for the late Brooklyn Dodgers fan Hilda Chester. In his welcoming remarks, Master of Ceremonies Terry Cannon lauded Chester by saying, “As a young woman growing up in Brooklyn, Hilda’s dream was to play in the big leagues. Thwarted as an athlete, she turned to rooting, and in the community of rooters she became royalty.”

A wonderful rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” was performed by freelance cellist Roger Lebow, a Boston Red Sox fan who serves as principal cellist of the Los Angeles Mozart Orchestra and is a founding member of the chamber group XTET.

The National Anthem was followed by an announcement by Terry Cannon that an annual award, named in memory of Hilda Chester, had been established by the Baseball Reliquary. The award, to be known as the Hilda, consists of Hilda Chester’s signature noisemaker, a cowbell, encased and mounted in a Plexiglas box bearing an engraved inscription. Cannon remarked that the award “has been created to call attention to baseball fans and their importance to the game and its history. Despite suffering through strikes and lockouts and the various economic indignities that major league baseball has inflicted on them, the fans are always there to cheer for and to live, love, and die for their hometown teams. The motion pictures have their Oscar, television has its Emmy, and now baseball has its Hilda. And hopefully, over the course of time, this award will help remedy the woeful under-representation of the paying customer in the game’s official history.”

The inaugural Hilda Award was then presented to Southern California resident Rea Wilson, who was in attendance. In the summer of 2000, Mrs. Wilson traveled 18,000 miles and visited every major league ballpark in the United States and Canada. “What made this odyssey all the more remarkable,” Cannon added, “was that Mrs. Wilson was 77 years old, she traveled alone, and drove the entire trip in her van, sleeping many nights in the van on a mattress where bench seats once were.”

Keynote Address: Dave Frishberg

By way of introducing the afternoon’s keynote speaker, Terry Cannon shared some contemplations on the subject of baseball and music. First, he listed several former ballplayers who played musical instruments, including Eddie Basinski (violin), Stan Musial (harmonica), Satchel Paige (guitar), Maury Wills (banjo), Horace Clarke (vibraphone), and Carmen Fanzone (trumpet and fluegelhorn). Then Cannon described the musical zaniness of the Dodger Sym-Phony, that wacky band of merrymakers who would mock, deride, and razz umpires and opposing players at Ebbets Field. Also recalled were Phil Linz, the New York Yankees utility infielder who stepped into baseball immortality in 1964 with his harmonica version of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” and “Disco Demolition Night,” which Cannon cited as “probably the most infamous confluence of baseball and music in the game’s history.”

By way of introducing the afternoon’s keynote speaker, Terry Cannon shared some contemplations on the subject of baseball and music. First, he listed several former ballplayers who played musical instruments, including Eddie Basinski (violin), Stan Musial (harmonica), Satchel Paige (guitar), Maury Wills (banjo), Horace Clarke (vibraphone), and Carmen Fanzone (trumpet and fluegelhorn). Then Cannon described the musical zaniness of the Dodger Sym-Phony, that wacky band of merrymakers who would mock, deride, and razz umpires and opposing players at Ebbets Field. Also recalled were Phil Linz, the New York Yankees utility infielder who stepped into baseball immortality in 1964 with his harmonica version of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” and “Disco Demolition Night,” which Cannon cited as “probably the most infamous confluence of baseball and music in the game’s history.”

Eschewing the podium for more familiar confines, Dave Frishberg performed his keynote address seated at the piano. Since his days as the house pianist at the Half Note Cafe in New York, Frishberg has been considered one of the outstanding pianists in jazz and is an internationally-recognized composer and lyricist. Interestingly, this was the first baseball-related ceremony that Frishberg has performed at, despite his enormous contributions to the encyclopedia of baseball music.

Frishberg began by playing his lovely ballad, “Van Lingle Mungo,” the lyrics of which are composed solely of vintage ballplayers’ names. He acknowledged Jim Bouton, who, while working as a television sportscaster in the early 1970s, created interest in the song by playing it during the baseball season. Frishberg then proceeded to recall his only encounter with Van Lingle Mungo, the pitching star for the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants in the 1930s and ‘40s whom the song is named after. Both the composer and ex-pitcher were scheduled to appear on Dick Cavett’s television show, when they met briefly prior to going on stage. “Oh, you’re the guy with the song,” Frishberg remembers Mungo saying. “I said right. He was very nice and he said I really like the song. Of course, he was a big celebrity now down in Pageland, South Carolina. So he takes me aside and says, tell me, when do I get the first check on this. I saw the look in his eyes and he was not kidding. He really expected there was going to be a check. And he was a big guy and looked like he might be a little unreasonable, you know. I thought fast, though, and I said, well look, nobody’s gonna make any money off this song — that’s number one. Number two, if anyone does make any money off of it, I’m gonna be the last one. And I said, you’re never gonna see a cent off this. He said, but it’s my name. I said I know. The only way we can get even on this is you gotta go home and write a song called ‘Dave Frishberg.’ So he laughed and hit me on the back and he said, that’s okay, I like the song anyway. I lost contact with him after that, but I did send him a birthday card every once in a while.”

Frishberg’s performance of his baseball songs lasted nearly 30 minutes and included such favorites as “Dodger Blue,” “Matty,” and “The Dear Departed Past.” The presentation offered a wonderful illustration of the interrelationship between baseball and art, as well as proof that the national pastime has been a most worthy subject for American music composers.

Satchel Paige

The afternoon’s first inductee was introduced by Amy Essington, a Negro League historian and a Doctoral student in American History at Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. Essington has written essays on Effa Manley, Rube Foster, and other figures associated with Negro League baseball, and has served internships at both the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution. She is actively involved in numerous professional organizations, including the Western Association of Women Historians.

The afternoon’s first inductee was introduced by Amy Essington, a Negro League historian and a Doctoral student in American History at Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. Essington has written essays on Effa Manley, Rube Foster, and other figures associated with Negro League baseball, and has served internships at both the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution. She is actively involved in numerous professional organizations, including the Western Association of Women Historians.

“He couldn’t have been real, could he?” Essington began. “He had to be the figment of some fiction writer’s overactive imagination: A tall, lanky, brash, cocky, fast-talkin,’ fun-lovin’ philosopher from Alabama who could throw a baseball right past you before you even saw the thing. Is it even possible? Could someone really have thrown a baseball that hard, or played that long, or talked that fast? Of course. Because with Leroy Robert Paige, anything was possible. He was Walter Johnson, P.T. Barnum, Stepin Fetchit, Al Capone, and Paul Robeson, all rolled into one. He played with Jackie Robinson and Cool Papa Bell. He schmoozed with Joe Louis and Louie Armstrong. He pitched against Babe Ruth and Mickey Mantle. He went everywhere and did everything.”

Essington provided a brief biographical sketch of Paige’s baseball career, interspersing examples of his homespun phraseology and philosophy. “Aided in part by his own legend-spinning,” Essington said, “Satchel quickly established himself as the Negro Leagues’ hardest thrower, most colorful character, and greatest gate attraction, baffling hitters with pitches like the Trouble Ball, Bat Dodger, and Hesitation Pitch. He’d walk a batter, then yell over to him at first base: ‘There you is, and there you is going to stay!’ Then he’d call in all his outfielders and proceed to strike out the side.”

Essington opined that the “one thing Satchel never got credit for is his smarts. He could play the buffoon, all right, but mostly it was just an act for white people. He knew that’s how they expected him to act, and if he didn’t — well, then maybe next time Satchel Paige came through town, they might not come out to see him pitch. So he’d put one over on them and milk the minstrel-show nonsense for all it was worth.”

Essington recalled that when the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown decided to allow Negro Leaguers into its hallowed shrine in 1971, Satchel Paige was the first player chosen. When Satch heard his plaque would go in a separate section (described by Essington as “a sort of immortal, eternal segregation”), he said, “I ain’t goin’ in no back door.” In a very poignant closing to her introduction, Essington remarked, “So Cooperstown changed its mind, and decided to put Satchel’s plaque in the same room with Babe Ruth’s and Dizzy Dean’s and Tris Speaker’s. And thanks to Satchel, Negro Leaguers have been going in the front door ever since. And so, it is with great pleasure that we now welcome Satchel Paige into the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals — through the front door. Satchel, here you is, and here you is going to stay.”

Essington recalled that when the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown decided to allow Negro Leaguers into its hallowed shrine in 1971, Satchel Paige was the first player chosen. When Satch heard his plaque would go in a separate section (described by Essington as “a sort of immortal, eternal segregation”), he said, “I ain’t goin’ in no back door.” In a very poignant closing to her introduction, Essington remarked, “So Cooperstown changed its mind, and decided to put Satchel’s plaque in the same room with Babe Ruth’s and Dizzy Dean’s and Tris Speaker’s. And thanks to Satchel, Negro Leaguers have been going in the front door ever since. And so, it is with great pleasure that we now welcome Satchel Paige into the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals — through the front door. Satchel, here you is, and here you is going to stay.”

The induction was accepted by Warren Paige, who, at age 35, is the youngest of Satchel’s eight children and a resident of Kansas City, Missouri. He spoke very briefly, thanking the members of the Baseball Reliquary on behalf of the Paige family for honoring their late father.

Jimmy Piersall

In his introductory comments about Jimmy Piersall, Terry Cannon noted that the first nine inductees to the Shrine of the Eternals (including Dock Ellis, Curt Flood, and Bill Veeck Jr. in 1999 and Moe Berg, Bill Lee, and Pam Postema in 2000) share a common literary interest. Eight of the nine, in fact, have written books, and the only one who didn’t was Moe Berg, probably the most erudite and intellectual player in the history of the game. (Berg was, however, the subject of at least seven books published in several languages.) Prior to reading a moving excerpt from Jimmy Piersall’s autobiography, Fear Strikes Out, published in 1955, Cannon maintained the book was “far more than one of the great comeback stories in baseball literature. Piersall exhibited extraordinary courage in detailing his mental breakdown and his subsequent recovery and return to the playing field. In the Eisenhower era, mental illness was not a topic of polite discussion at the American dinner table, not to speak of in the macho and conformist world of the professional athlete. Piersall’s book was courageous in its attempt to make readers aware of the causes of his mental breakdown and, most importantly, of the fact that mental illness can be a curable disease.”

Due to previous commitments, Jimmy Piersall was unable to personally attend the ceremony and asked his stepson, Robert Jones, to accept his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals. A screenwriter based in Hollywood for the past 15 years, Jones is the head of his own company, Deadwood Productions. Although Jones’ relationship with his stepfather underwent some difficult moments in its early stages, he described Piersall now as his “best friend and mentor. He’s helped me through a lot of tough times with his own life stories. He does the same thing with the kids, as he calls them, that he coaches. He coached for the Cubs for 14 years until a year ago. He might be coaching the game, but then he’d tell them about life, what to look forward to and what to be careful of, in his own unique monosyllabic way. That’s just how Jimmy is. He’s not an erudite speaker, but he gets the point across, which you end up loving him for.”

Due to previous commitments, Jimmy Piersall was unable to personally attend the ceremony and asked his stepson, Robert Jones, to accept his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals. A screenwriter based in Hollywood for the past 15 years, Jones is the head of his own company, Deadwood Productions. Although Jones’ relationship with his stepfather underwent some difficult moments in its early stages, he described Piersall now as his “best friend and mentor. He’s helped me through a lot of tough times with his own life stories. He does the same thing with the kids, as he calls them, that he coaches. He coached for the Cubs for 14 years until a year ago. He might be coaching the game, but then he’d tell them about life, what to look forward to and what to be careful of, in his own unique monosyllabic way. That’s just how Jimmy is. He’s not an erudite speaker, but he gets the point across, which you end up loving him for.”

Jones told a number of anecdotes about Piersall, including some humorous broadcasting and fishing stories, and concluded by saying, “Everybody talks a lot about the antics, but you go through his scrapbooks and read about the clutch hits, slamming against the wall for catches, and you realize this guy was good. He’s intense about baseball, but feels the game should also be fun. He’s done a lot and been through a lot.”

Jim Bouton

No stranger to the Shrine of the Eternals ceremonies, Albert Kilchesty, the Baseball Reliquary’s Archivist and Historian, introduced the afternoon’s final inductee, Jim Bouton. He spoke about the impression Bouton made on him as a youngster: “Today I am very happy to call Jim an eternal. And although I’ve never met him before, I have always called Jim Bouton a friend. Sort of like your favorite baseball uncle or family relation that turns you on to something really important and crucial when you’re at an age to really begin looking at the world in a wider way. And he changed my life forever. I’m speaking, of course, about the publication of his book, Ball Four.”

With his previous exposure to baseball literature limited to juvenile books in which players were paragons of Christian virtue and athletic prowess, Kilchesty found that “at the tender age of 12, reading Ball Four completely demystified the life of professional ballplayers and opened my eyes to the adult world of the workplace. Ball Four was a central moment in my life as an artist and a writer.”

Continued readings of the book as an adult resulted in further discoveries: “While baseball is the central backdrop to the book, Ball Four is about a hell of a lot more than baseball. It’s a book about life. It’s a chronicle about a fighter, a survivor, a bulldog, if you will. Someone struggling to make sense of an environment in which the inmates are running the asylum. Somebody struggling to hang onto his career literally by his fingertips. And the great trope in the book is Bouton’s attempt to master the knuckleball, which, of course, as we all know, is thrown with the fingertips.”

Kilchesty lauded Ball Four as one of the period’s most important sociological documents: “Ball Four reveals with surgical precision the complexity, the uncertainty, and the insecurity of ballplayers; the penurious conduct of the owners; and the difficulty in establishing and maintaining relationships in life with children, wives, and your family. I also found in subsequent rereadings of the book that Jim in Ball Four is a direct descendant of the great anti-heroes of American fiction in the 1950s and ‘60s, too. I’ve often thought of Jim Bouton’s relationship to baseball in Ball Four as similar to Yossarian’s relationship to the Second World War in Catch-22. Both of them seemed to be trapped in systems beyond comprehension and seemed to be the only sane people there to see what was going on.”

“But most important for me and for the rest of the reading public,” Kilchesty concluded, “the appearance of Ball Four in 1970, coinciding with Curt Flood’s suit against major league baseball to revoke the reserve clause, altered the game forever. Without Curt Flood, without Jim Bouton, we would not have free agency today.”

In his opening comments, Bouton referred to the previous two inductees, saying he was thrilled to be mentioned in the same breath as Satchel Paige and recalling a humorous story about Jimmy Piersall’s intensity as a ballplayer. Bouton generated much laughter in the audience by following, “It’s a great honor to be inducted into the Shrine of the Eternals, but also scary as hell. Does that mean I’m dead already and I’m living in a parallel universe? My arm belonged in a reliquary about 30 years ago, I know that. I got a letter from a friend of mine who was the manager of the last team I played for. I played in a good semi-pro league with young guys all the way until I was 57 years old. I finally retired from semi-pro baseball because I got tired of autographing home run balls hit off me by guys named Jason. Anyway, the manager of the team was a guy by the name of Jack Kieley, and he sent me this letter in which he said, ‘Congratulations, I guess. Not knowing the meaning of the word reliquary, I looked it up in my dictionary and read that it was a small box, casket, shrine, etc. for keeping or exhibiting a relic. I don’t know whether to congratulate you or offer condolences.’”

In his opening comments, Bouton referred to the previous two inductees, saying he was thrilled to be mentioned in the same breath as Satchel Paige and recalling a humorous story about Jimmy Piersall’s intensity as a ballplayer. Bouton generated much laughter in the audience by following, “It’s a great honor to be inducted into the Shrine of the Eternals, but also scary as hell. Does that mean I’m dead already and I’m living in a parallel universe? My arm belonged in a reliquary about 30 years ago, I know that. I got a letter from a friend of mine who was the manager of the last team I played for. I played in a good semi-pro league with young guys all the way until I was 57 years old. I finally retired from semi-pro baseball because I got tired of autographing home run balls hit off me by guys named Jason. Anyway, the manager of the team was a guy by the name of Jack Kieley, and he sent me this letter in which he said, ‘Congratulations, I guess. Not knowing the meaning of the word reliquary, I looked it up in my dictionary and read that it was a small box, casket, shrine, etc. for keeping or exhibiting a relic. I don’t know whether to congratulate you or offer condolences.’”

Bouton proceeded to acknowledge family members and former players and coaches who influenced his career, including Yankees pitching coach Johnny Sain and all of his teammates: “Mickey, Whitey, Yogi, Elston Howard, and Hector Lopez, who gave me my only vote when I ran for player representative of the Yankees.” He also thanked Ralph Houk for trading him to the Seattle Pilots and Joe Schultz “for becoming the greatest character an author ever had to work with. . . The best way to describe Joe is he was the opposite of Vince Lombardi. Joe felt sorry for us. He told us not to feel bad, we just didn’t have the talent.”

In reference to Ball Four and the controversy surrounding it, including Commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s ill-fated attempts to ban the book, Bouton reflected, “Looking back on it, I realized why the owners and the baseball commissioner were upset with Ball Four. It had nothing to do with the locker room stuff, or running around on the roof of the hotel ‘beaver shooting,’ but it had to do with the fact that Ball Four was the first book to tell people how difficult it was to make a living in baseball. Ball Four became part of the evidence in 1975 at the arbitration hearings in the Andy Messersmith case. The arbitrator accepted Ball Four because it was based on contemporaneous notes and that was the hearing at which baseball players were declared free agents. The owners were then forced to sit down with the players and renegotiate the current system of six years of major league service before they were allowed to become free agents. And I know a lot of people think baseball players make too much money these days. But here’s the way I look at it: For a hundred years, the owners screwed the players. For 25 years, the players have screwed the owners; they’ve got 75 years to go.”

Bouton then offered a mordantly hilarious forecast for baseball in the 21st century, mixed with generous helpings of satire and irony. Bouton foresees entertainment conglomerates, which own teams and networks, buying each other up and leading to one company owning all the teams. The players’ share of revenues would drop from 51% to 1%. “It would be like the old days,” Bouton mused. “Reporters could be happy again since they know the players are worse off than they are.”

The major difficulty will be selling baseball to the American public since there will be no homegrown players, thanks in large part to the disappearance of sandlot baseball. Bouton contends that the search for an American-born ballplayer will inevitably lead to prisons: “With more kids living below the poverty line and young kids being tried as adults, prisons will be overflowing with young talent. Prison sports will become widely popular, especially to television viewers of the highly-rated PSN — Prison Sports Network. Prison League Baseball (PLB) will be particularly exciting. As commentators might put it, these guys want to play ball so bad, they’ll run through a wall for you. Baseball terms like ‘stealing,’ ‘hit-and-run,’ and ‘leaving the yard’ will take on a new meaning. The Prison Sports Network, one of the few remaining independents, will even have their own Web page, www.con.com. The death penalty will be eliminated for gifted athletes. Prisons will become our new sandlots, the playing fields of our future heroes. With taxpayer dollars going to new stadiums at the expense of our public schools, responsible parents will try to get their kids into a good prison.” On that optimistic note, Bouton concluded his acceptance speech.

Induction Day photographs courtesy of Larry Goren

This Shrine of the Eternals 2001 Induction Day was made possible in part by a grant from the California Council for the Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Dave Frishberg’s appearance was sponsored in part by a grant from the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and the Recording Industries’ Music Performance Trust Funds through the Professional Musicians Union Local 47; and by LIVE! @ your library, an initiative of the American Library Association, with major support from the National Endowment for the Arts, Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund, and John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Dave Frishberg’s appearance was sponsored in part by a grant from the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and the Recording Industries’ Music Performance Trust Funds through the Professional Musicians Union Local 47; and by LIVE! @ your library, an initiative of the American Library Association, with major support from the National Endowment for the Arts, Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund, and John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.