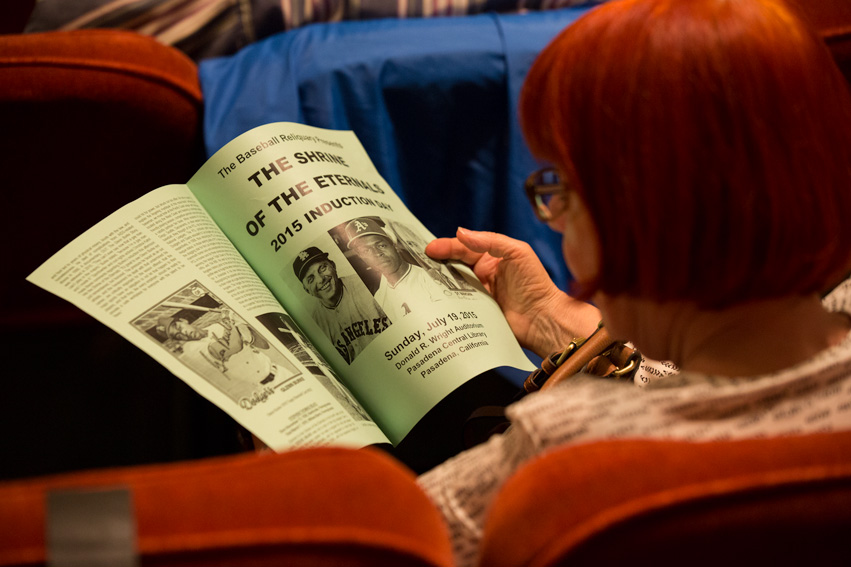

On a pleasant summer afternoon in Pasadena, California (with the previous year’s record-setting 112 degree temperature only a lingering memory), a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 200 people attended the 2007 Induction Day ceremony for the ninth class of electees to the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals on Sunday, July 22, 2007. The setting was the Pasadena Central Library’s Donald R. Wright Auditorium, and the attendees were there to celebrate the inductions of Yogi Berra, Jim Brosnan, and Bill James, who were elected by the membership of the Baseball Reliquary in voting conducted in April 2007. The inductees received the highest number of votes from a ballot consisting of fifty candidates.

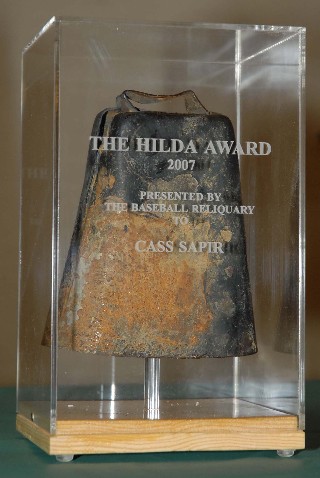

The keynote address was delivered by Tomas Benitez. The ceremony also featured the presentation of two annual awards: the 2007 Hilda Award went to Cass Sapir and the 2007 Tony Salin Memorial Award went to Mark Rucker.

For additional coverage of the ceremony, see the following articles: “Baseball and the Sublime: Celebrating Language and Eternity with the Baseball Reliquary,” by Don Malcolm [link no longer valid]; “Down the Hall,” by Steve Henson; and “An Event for the Eternals,” by Rich Lederer.

~ All Photographs Courtesy of Jeff Levie ~

Keynote Address

Ardent Fans of the

Imperfect Beauty of Baseball

by Tomas Benitez

Ladies and gentlemen, distinguished inductees and representatives of those inductees, thank you for being here today and thank you for the honor of welcoming you to the annual induction ceremony of the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals, 2007.

I was sitting with a group of friends a few nights back, excitedly talking to them about how I was so honored to be delivering the keynote address today, talking about the Baseball Reliquary and of the achievements of Jim Brosnan, Bill James, and Yogi Berra.

They all knew Yogi Berra by name, in fact they even misquoted him to me a couple of times; a couple of them think they had heard of Bill James, somewhere; and – who was the other guy? A writer; a baseball player? And, of course, the usual question we all get, what the hell is a baseball reliquary?

Maybe I was a little too enthusiastic, maybe I just went on too long as I am disposed to do, but I saw the familiar signs: the glazed over eyes, the condescending nods, and then the quick cut-off to another round of martinis. When the conversation resumed, we talked about reality TV, political sex scandals, no baseball. I cite this incident to underscore my pleasure at being here with you. I love my friends dearly, but there are times when we do not walk the same path. All of us here today, however, are from the same congregation, an open society yet a small but learned group of ardent fans of the game of imperfect beauty, the game of baseball.

If you are lucky, you play the game as a child, out on the street, improvising a Chevy for a base and the sewer as an automatic out. Not unlike the ivy in Wrigley, the Green Monster at Fenway, the game adapts to its environs easily enough. In my generation, the sandlot was really an empty lot before the Barrington Towers were built, that is, on the weekends with Dad, or back in East LA, empty lots were gardens gone abandoned, land not yet claimed by urban renewal. We played tripleheaders where the 10 meets the 5 and the 60, the East Los Angeles Freeway Interchange.

Sure, it was great to finally get a uniform from the park league or the YMCA and it was fun to finally play on a field that had grass where it was supposed to be, real bases and balls that did not have more tape than seam, but still, it is the improvised elements of the game which gave it its character, its improbability, and its imperfect beauty.

The ardent fan played from sunup to sundown, boys and girls of any ability and various ages, so many games and configurations of teams, changing the field in accordance with who drove home and who drove off, that we lost track of the games won or lost, but never the vital statistics, that is, how many hits we made in a day, starting with homers and ending with hits we call hits that may have been ruled errors, but who’s counting?

It was possible on occasion to overstep the boundary of acceptable devotion for the game. My mother’s lamp with the ceramic panther base and tropical floral shade will forever be the last thing I broke with a well-hit whiffle ball inside the living room one night. I got a double, however I got whiffle ball banned forever from inside my home.

But the ardent fan plows on, and when he is not playing baseball, he is reading baseball, at least that is the way it was for our crew. We shared dog-eared editions of the Duane Decker series, fighting over who got the copy of Southpaw from the library next, or the ten-cent copy of World Series by John Tunis, rescued from the used book rack near the dirty magazines in the back of the Rexall on Wabash. Sure there were other writers well before my youth; no other team sport has inspired so much literature and art. My uncle gave me his copy of Jackson Scholz’ Batter Up, so hallowed, I didn’t put it into circulation with my pals and as a result I still have it. There were the biographies of our baseball heroes, always it seems written with or as told to Arnold Hano. And then, Along Came Brosnan.

Jim Brosnan looked like one of us, that is, he did not look like a baseball player, rather he seemed suited to be a librarian, with his thick glasses and his reserved mien. He was surely quick-witted and well-spoken, his teammates called him Professor, and a few other names after he was published. But he did not appear to be a man who made a living tossing around a baseball. Yet he certainly did and that was the crux of his gift.

I contend his appearance enhanced his role in the annals of the literature of the game, made him accessible, and thus edified the impact of his two famous books, The Long Season and Pennant Race. He made the game more tangible than it had ever been. He took us into the locker room, onto the bench and bullpen, and more so, he gave us an ear to hear the genuine vernacular, language certainly modified for the standards of those times, but real words spoken in real settings nonetheless.

He was the precursor to Jim Bouton’s breakthrough expose, and unfortunately he took the first steps in a dastardly trail that led from The Bronx Zoo to the magnum opus of that great baseball scholar, Jose Canseco. But he is not to blame, for given his time, he managed to make the game more real while still holding fast to his own sense of dignity. He didn’t write two great American novels, he just wrote two great books about what he knew. There are better writers, such as Roger Angell, Thomas Boswell, and the dear friend we lost too soon, David Halberstam, but Brosnan played the game. He wrote about it, and he did it first.

The base of knowledge of the ardent fan was found on the back of a baseball card, where all the inner secrets of the game were laid out for you to be decoded, as eventually, a genius among us, would indeed do that very thing. But we took that which was given to us at the time and we made it our currency, our measure of expertise, and our quest for Wisdom.

I am told that mathematics has its own built-in musicality, to which I confess to being tone deaf. And as for statistics, at its core it is merely the act of building a compendium of numbers that can be molded to the vessel, which needs be served. But analysis, that requires the application of scientific and subjective thinking to otherwise plain facts.

Thus, to do so gives impetus to the thing so often we fear, good or bad, change. To derive new methods of measure, amplify and endow a set of probabilities, and in doing so challenge the glacier of conventional wisdom, well you gotta know you’re just asking for trouble.

When Bill James came upon the scene he was greeted with the kind of warmth from the baseball establishment that is usually reserved for favorites such as Marvin Miller or a gaggle of super agents who show up unannounced and uninvited at spring training. And I imagine for Mr. James looking at a game is a little like what it must have been for Galileo looking up at the sky and thinking to himself, boy I am in for it now. But nonetheless he persevered, made inroads, and, for the ardent fan, opened the game to a new vision that only served to make the game more vital. Thus, the more the information, the more we know what we do not know, and the divine mystery of baseball is intact.

James did not divest the game of its charm or serendipity, rather he made it more so, he fed the ardent fans more fodder for debate, and gave baseball statistics a sense of musicality. For in the end, it is a game based upon a round object being hit by another round object, and what we know is that after all analysis of statistics and predictions, anything is possible.

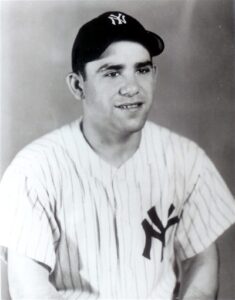

Speaking of imperfect beauty, let us speak of our final honoree, Yogi Berra. Could we have loved him any less if we knew him as Lawrence? I would hope so but I think not. Here is a man who took the gifts of his stumpy body and broad face and remarkable skill and turned them into the prototype expectation of what we want a catcher to look like.

Oh your first baseman is a lanky left-handed fellow, and the shortstop is gonna be the team fireplug, but a catcher, he is the bulldog on the field. His nickname is Pudge or Smoky. His hands are ugly, and he can’t run worth a damn, but without him, you don’t have a game. The pitcher might be the captain of the ship, but you don’t go anywhere unless you have a chief down in the boiler room to keep the screws turning. Those guys are catchers. Here I have to disclose my own special prejudice because I was a catcher. I read The Catcher in the Rye the first time when I was 13 because I thought it was a book about a catcher. Well, it was, but it wasn’t about baseball. It was still a very good book.

Imagine being the best at something, anything, better than anyone else? Yogi Berra is listed as number one in Bill James’ book, and Casey Stengel called him My Man long before that phrase became commonplace. He knew how much Yogi knew the game.

He was the guy who caught the only perfect game ever thrown in a World Series. He was a three-time MVP during his tenure on all those remarkably talent-laden Yankee teams. He was a 15-time All Star over three decades, and yet, what is it that really brings us here today? What is it about this wonderful baseball player that makes this day necessary?

I doubt you will find any other athlete in any other arena that has so influenced popular vernacular. He has been likened to Sheridan’s Mrs. Malaprop, but what she did was use the wrong word at the wrong time – what Sheridan did was plot to get the laugh he wanted. With Yogi, he has made us laugh yet he has left us with a profound wisdom, a double take that I get. Nobody goes to that restaurant anymore, it’s too crowded – I get that. If you can’t imitate him, don’t copy him, and my favorite, the one that took Yogi into the world of Zen: What time is it? You mean now? I get that. I get all of it, don’t you?

I contend that we are here today to honor three inductees whose ability to influence the game of baseball is the least of their achievements. In their relative careers, they have not only enhanced the imperfect beauty of the game, but they have also certainly elevated our popular culture and American patrimony. Thus to this group of ardent fans, it is we who are honored to be honoring them. Thank you Jim Brosnan, thank you Bill James, and thank you Yogi Berra. Thank you Terry, Mary, and all the Baseball Reliquary, and let’s play ball. Muchos gracias.

Yogi Berra Induction Acceptance Speech

Yogi Berra

I want to thank the Baseball Reliquary for making this day necessary. Truth is I’m not sure what this Reliquary is. But since Jim Brosnan and Bill James are also being inducted, and those guys are pretty good, I guess it’s a pretty good place. Thank you for thinking of me.

I’m sorry I can’t be here today because I’m somewhere else. But I appreciate Charlie accepting this honor for me. Charlie’s always been a great backup, a great teammate, and a great guy. And he probably has more of my stuff than I do in our museum in New Jersey.

Also my thanks to Toni for reading this – I don’t know her but she must be a great gal because she was related to a great man. Casey used to call me his assistant manager, but he didn’t need any assistant. He was a good manager and glad he believed in me because he knew what he was doing. I just want to say, I’m eternally glad I got to play the greatest game in the world – baseball. Thank you and God bless.

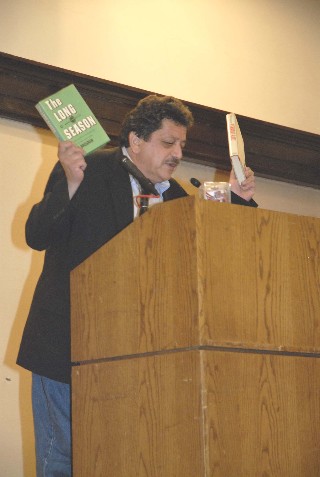

Jim Brosnan Induction Introduction by John Schulian

Jim Brosnan

I’ve always thought of Jim Brosnan as complete in a way that few other players have been in the whole sprawling history of baseball. Of course, if you look at nothing but the cold hard facts of his career, you might call me delusional. Brosnan came off the Cincinnati sandlots, where he grew up playing with Don Zimmer and Jim Frey and considered himself lucky when the Cubs signed him out of high school 60 years ago. A pitcher lucky to be a Cub? Broz would soon learn what it meant to be naïve.

He survived by letting his inner realist emerge and went on to play in the major leagues for nine seasons. In 1954 and from 1956 to 1963, as a starter and reliever with four teams – the Cubs, the Cardinals, his hometown Reds and the White Sox – he won 55 games, lost 47 and had 67 saves, all to the tune of a 3.54 earned-run average. He was, in his own words, “an average professional baseball player.”

But he rose far above that description with a statistic that the Baseball Encyclopedia fails to note. Number of books published: two. Both were nonfiction, written by him in diary form over the course of two baseball seasons. Their titles, as I hope you know, are The Long Season and Pennant Race. There is nothing average about either one. They are, rather, a window into what made Jim Brosnan a complete pitcher – smart, funny, insightful, irreverent, marvelously well-written and, most important, honest.

Pennant Race follows the Reds’ march to the 1961 National League championship. Brosnan salted it with one well-observed gem after another, the best remembered of which may be this: “Candlestick Park is the grossest error in the history of major league baseball. Designed at a corner table in Lefty O’Doul’s, a Frisco saloon, by two politicians and an itinerant ditch digger, the ballpark slants toward the bay – in fact, it slides toward the bay and before long will be under water, which is the best place for it.”

It was, however, The Long Season, a chronicle of the 1959 campaign, with which Jim Brosnan made history. This is not the fiction that Ring Lardner, Bernard Malamud and countless other non-playing writers have served up. Nor is it a kid-friendly biography of the kind that has cluttered bookstores since publishers discovered the market for baloney and outright lies.

Brosnan used The Long Season to take readers onto the field, but he didn’t stop there. His tour continued on into the dugouts, clubhouses, planes, trains and hotel rooms where baseball players lived out their lives, from February until October. He laid bare strengths and weaknesses, triumphs and indignities, good times and bad, his own as well as his teammates.’ Granted, he realized his era wasn’t ready for the vulgarity that is a staple of baseball conversation. And he steered clear of the sexual shenanigans we have come to realize are part of big league recreation. (In the days he wrote about, there wasn’t even a designated hitter, and the champions of the two eight-team major leagues went straight to the World Series.) And yet Brosnan’s readers – not just baseball fans but thinking people interested in the human condition – got the picture.

It was right there on Page 1. Broz, working in the off-season at a Chicago advertising agency, calls home to see if there are olives for martinis. (That was the first surprise: He didn’t drink milk.) His wife, Anne Stewart, tells him his contract from the Cardinals has arrived. He’s coming off a strong season and looking for a big raise, all the way to $20,000. On Page 2, he finds out the Cards have no intention of giving it to him.

Welcome to the big leagues before agents and free agency, when the ballplayers were indentured servants.

By lifting the veil of secrecy from his world, Brosnan ventured where no player had ever gone. There are those who say that John Montgomery Ward, a 19th-century fireballer, was the first to break this literary ground. But my old friend Jerome Holtzman, baseball’s tireless unofficial bibliophile, doesn’t include anything by Ward in his collection. And as Broz once told me, if Jerry Holtzman doesn’t have it, it doesn’t exist.

So Brosnan was the first of baseball’s dugout literati. Without him, there might have been no Ball Four by Jim Bouton a decade later, which would have been a loss of epic proportions. Then again, Sparky Lyle might not have put his name on the scabrous Bronx Zoo, which would have been a blow for good taste. And what to say of Jose Canseco and Juiced? You take the wretched with the sublime, I guess.

But never forget this: The Long Season by Jim Brosnan was, and is, the best of its kind.

Not that there weren’ those who howled angrily when it was published. Some were the chowderheads in baseball too dim to appreciate his affectionate portrayals of players like Don Blasingame and Smoky Joe Cunningham and his reverence for Fred Hutchinson, his manager in Cincinnati. I’m embarrassed to say that other detractors were sportswriters who may not have known what to make of a player who wore glasses, smoked a pipe and read books. As Brosnan wrote later, “I was, on those accounts, a sneak and a snob and a scab.”

But I am here to tell you that he was a model of intellectual courage. It’s a quality in short supply no matter how long the parade is of hitters willing to risk stopping a 97-mile-an-hour fastball with their heads. If there were more courage of the mind – if there were more ballplayers who could face the truth and stand tall when they did it – we might know, for instance, just how rampant steroid abuse was during the Great Home Run Epidemic. But Brosnan was, obviously, a rarity.

When he wrote about his life in baseball, he did it with candor sustained by wit. You can turn randomly to almost any page in The Long Season and find an example of what I’m talking about. Consider this: “I maintain a small library in my locker and in the clubhouse. Nothing like a book to keep your mind from thinking.”

Or this, when Broz learns that the Cards have traded him to Cincinnati, just as the Cubs once traded him to the Cards: “I sat back on the couch, half-breathing as I waited for indignation to flush good red blood to my head. Nothing happened. I took a deep breath, then exhaled slowly. It’s true. The second time you’re sold you don’t feel a thing.”

And then there is my favorite, which tells so much about the era and the art of not just pitching but of getting your mind right to do it: “[Willie] Kirkland ran up to the plate, eagerly. My old homer-hitting buddy. Six home runs off me in three years. I stepped back off the mound to hate Kirkland with my eyes. (Early Wynn says a pitcher will never be a big winner until he hates hitters.) I growled a negative growl at [Dutch] Dotterer’s sign. No, sir, if Kirkland hits a home run off me on this pitch it will be from a prone position. Down he went. My control was excellent. He fouled off the next slider, fouled off a curve, and fanned on a fastball right under his chin.

“Well, that pitch did it. When a pitcher can rid himself of the feeling that he can’t get a certain hitter out, he knows he’s got good stuff. The Giants stared at me for six innings, waiting to see Old Broz, Old Nervous Broz, start to waver, start to think on the mound. They waited in vain . . .”

Brosnan’s improvement as a pitcher was a welcome side effect of The Long Season. As he told me when I interviewed him in 1980, “I was rid of all the B.S. that had always cluttered my mind. I’d always dwelled on my bad days, my embarrassments, and as a result, I was just competent. The book finished that. It gave me the self-confidence I’d always lacked.”

Think of that for a moment: He got his act as a pitcher together and we got a classic in baseball literature. To my ears, that sounds like one of the greatest trades ever.

So it is that we are gathered here today to salute the pitcher, author and freethinker who was known by so many names: Broz in his own thoughts, Meat to his wife, and The Professor to his teammates. Now we have something else to call him: Eternal.

Please join me in welcoming Jim Brosnan to the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals.

The full text of John Schulian’s introduction also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, under the title “Before ‘Ball Four,’ there was Brosnan,” in the July 22, 2007 edition.