We are pleased to share this timeless essay by Dennis Petticoffer, originally published in the December 1976 (Vol. II, No. 3) issue of Follies magazine.

We are pleased to share this timeless essay by Dennis Petticoffer, originally published in the December 1976 (Vol. II, No. 3) issue of Follies magazine.

DiMaggio. Mantle. Ruth. Williams. Cobb. They were more than just names: they were legends. If there is a classic tradition, if there is a mythology in American life, it flourishes in the accomplishments of DiMaggio, Mantle, Ruth, and a host of other great baseball stars. Every boy has his personal favorites.

The legendary stars were not heroes to me. I liked the little guys – the ballplayers who struggled just to stay in the major leagues – the men who were just names on a scorecard for one or two seasons, then were forgotten.

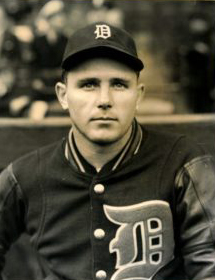

Virgil Trucks

My heroes were the ballplayers who came to bat in a dearth of silence, who popped up, fouled out, or took three quick whiffs at fastballs that sailed high and tight. It wasn’t their humble accomplishments that attracted me, it was their names – great baseball names. Virgil Trucks. Gene Leek. Tom Butters. Fritz Brickell.

In the back of my brain, filed away like neat rows of dog-eared bubblegum cards packed tight in a shoebox, the ghosts of baseball’s past still visit me in moments of reverie. Choo Choo Coleman. Riverboat Smith. Joe “Piggy” Pignatano. Mel Roach. Jim Greengrass.

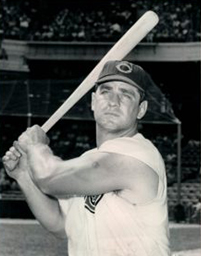

Ted Kluszewski

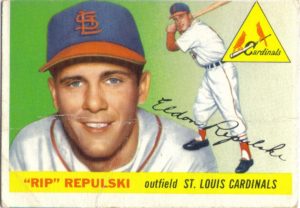

Then there were my favorites: who wouldn’t be a great ballplayer with a name like Rip Repulski? And how about Solly Hemus? That’s the kind of name you’d expect to see on a bag of fertilizer, or on a special brand of whiskey. Anyone with an appellation such as Moe Thacker, Moe Drabowsky, Clem Labine, Seth Morehead, Duke Carmel, or Sal Maglie surely couldn’t have an IQ above 50! And how about the first basemen? They were all obese gorillas, with unsightly chaws of tobacco deep in their jowls and sleeves rolled up to their armpits – guys who sported rugged names, like Rocky Nelson, Steve Bilko, and Ted Kluszewski.

Ah, the power of a name! Even the most sophisticated of men can be reduced to a drippy-nosed Little Leaguer at the mere mention of Clint Courtney, Jerry Lumpe, or Solly Drake. Even in college, while studying such esoteric subjects as the prosody of T.S. Eliot or the lyrical patterns of 17th-century French poetry, my mind would drift back to the world of sport. For every poetic concept I learned, I recognized a parallel in sports. The 14-line sonnet had its equivalent in the nine-man baseball lineup. (The first and fourth positions in the lineup – the leadoff and “cleanup” hitters – were as crucial to the batting order as the final couplet of a sonnet.) The 5-7-5 syllable pattern of haiku was matched by the 4-3-4 defense in football.

Dick Drott

And like poetry, the names of baseball players had a rhythm and sound that could be as enticing as the recited verse of Gerard Manley Hopkins. The trochaic charm of Larry Sherry or Whitey Herzog was outdone by the dactylic delightfulness of Danny McDevitt, Bobby Del Greco, and Billy O’Dell. And there were plenty of spondees – players with one-syllable names, like Gus Bell and Don Hoak. The Cub lineup of the late ‘50s even included a rhyming batting order, consisting of Irv Noren and Walt Moryn. And then there was the supreme assonance of Pee Wee Reese. But, of course, the most prominent poetic feature of baseball was the alliterating name: Mickey Mantle, Roger Repoz, Minnie Minoso, Jackie Jensen, Joey Jay, Bo Belinsky, Chuck Churn, and a whole raft of D’s from Dick Drott to the “Don’s” – Demeter, Dillard, and Drysdale. The list is endless.

Too often, in the midst of college lectures, my mind would wander from Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey” in the Valley of Wye, to the Cubs’ Wrigley Field in the conurbation of Chicago. While studying the classic elements of Elizabethan verse, I began to wonder if Billy Shakespeare could have pitched for the Yanks. He was a great writer, but who’s to tell what he might have done with a ball and mitt? And of course I knew John Milton, in his blindness, would have made an ideal umpire!

It was always with a sense of sadness that I pored over “Paradise Lost,” for I could only think of my own paradise lost – my unsatisfied desire to be a ballplayer. But I soon comforted myself in the notion that I was merely one of millions with the same unresolved dream. ‘And besides,’ I told myself, ‘greatness? Who needs it?’ Once you’ve reached the pinnacle of success, where do you go from there? It’s the struggle, the conflict, that makes life worth living.

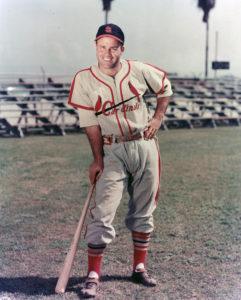

Joe Garagiola

Still, I couldn’t help thinking that I would have made a great mediocre player, in the tradition of Ed Fazio or Bobby Lillis. The game could use a name like mine – Petticoffer: the perfect name for a third-string shortstop, with a fear of line drives, no hitting power, and a penchant for losing pop flies in the sun. . . . But always ready to play – always prepared to step up to the plate with the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth with my team down by one – always ready to take a wild swing at a third strike!

Maybe Ruth was a great slugger; maybe Mays made the greatest catch in the annals of baseball; but the Toby Atwells and Jim Pagliaronis, the Ed Palmquists and Arnie Portocarreros – they were the men that made the game great! Sure, you could always count on Ted Williams to deliver a base hit, but when the Bob Ueckers and Joe Garagiolas came to bat, you never knew what to expect! Even guys like Wayne Terwilliger, who couldn’t hit a medicine ball with a three-by-four, occasionally delivered a clutch hit. It was the unsung heroes, the guys like you and me, who came to bat, struck out plenty, but at all times gave 100% – they were the ones that made the game of baseball the great institution it has become. Long live Walt Dropo and Johnny Herrnstein; Dutch Dotterer and Eddie Miksis!