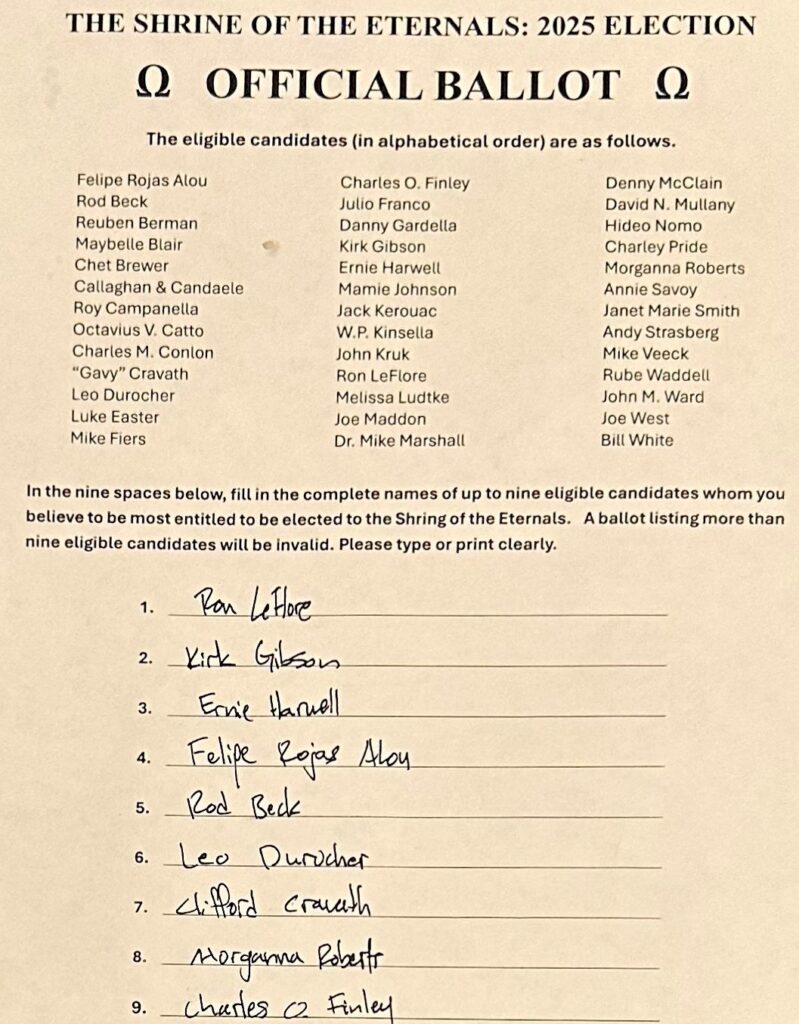

Remarks by Jean Hastings Ardell, July 17, 2016, Pasadena Central Library, Pasadena, California

Ninety years ago this very season, a young mother taught her four-year-old son how to safely cross Edgemont Avenue, in upper Manhattan. Mind you, this was not considered child neglect, for in those days many small children had the run of New York City. The child’s object in crossing Edgemont Avenue was to arrive at a popular venue just across the street known as the Polo Grounds, where he would meet his grandfather who gave him his pass to a seat above first base in the grandstand. (The pass was one of the perks enjoyed by his grandfather, a lieutenant in the NYPD, and the highest-ranking Jew in the police force, his grandson understood.) And so it was that this boy would watch the New York Giants play baseball. In training her son to safely cross Edgemont Avenue, this mother unleashed upon the baseball world an extraordinary fan and a talented writer. For that boy was, of course, Arnold Hano.

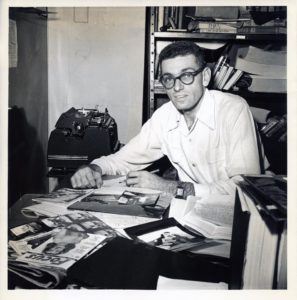

Young Arnold Hano

One of Arnold’s early acts of liberation came after he noticed that far more fun seemed to be going on in the bleachers, where the language was saltier, than in the more staid grandstand seats, and he moved his preferred location to that area of the ballpark, unto this day. He was soon able to finance his own independent excursions to the Polo Grounds by collecting pop bottles, which he stashed in the knickers young boys wore in those days, and redeeming the bottles for enough cash for a ticket to the bleachers: 50 cents. Early on Arnold grew enchanted with Bill Terry, the Giants’ star first baseman. “I am left-handed, and Bill Terry was left-handed,” Arnold explains. “He was my first hero.” And so began his study of the athletes who played the game he fell in love with.

With three teams in the city, New York in the late 1920s was a thrilling place for a young baseball fan. The Giants were in their glory years under manager John J. McGraw; down in Brooklyn, the Dodgers had become the Giants’ perennial nemesis; and nearby in The Bronx, the New York Yankees were beginning their ascendancy, led by Babe Ruth. Ensconced in the bleachers, Arnold soaked up baseball’s rhythms, fundamentals and stories, developing firm opinions on the game and its players. The greatest of them all was Babe Ruth, he maintains, because his talents went far beyond his famed home runs. He points out that Ruth broke fast, had an accurate arm, and always threw to the right base. And he stole 17 bases a season, twice.

Babe Ruth

Arnold was there when Ruth pitched for the New York Yankees on the last day of the 1933 season. Of Ruth’s performance that afternoon, he says: “He was cutting, he had finesse, he picked up the outside corner with his curve ball. He went the whole nine innings, and the Yankees won 7-5.” Ruth’s streak of 29-2/3 scoreless innings pitched in the World Series lasted until 1961. “So Ruth was a great pitcher,” Arnold concludes. “Not just a good pitcher.”

One of the great pleasures of being a kid about Manhattan was chance encounters with one’s baseball heroes. Just after Ruth pitched that game in 1933, Arnold spotted the great man on the street, walking with his wife and daughter. “Hey, Babe,” the nine-year-old Hano piped up. “How come ya didn’t strike anybody out the other day?”

Ruth laughed, he recalls, and said, “Aw, I wanted those palookas behind me to earn their keep.”

If New York City was rich in baseball, it was rich in stories, too, and Arnold’s writing career started early. He was 7 or 8 when his elder brother Alfie recruited him to help with his self-published Montgomery Avenue News, which the boys sold door-to-door. Their primary source was the lurid accounts in the city’s tabloids about the latest local gang assassinations, which sometimes happened as a mob boss lingered at his favorite restaurant. To this day, Hano prefers a seat in the restaurant that faces the door, with his back to the wall, a habit he shares with other New Yorkers.

Arnold Hano, U.S. Army, ca. 1941

He continued writing as a student at Long Island University, working for the school newspaper as sports editor and co-editor. After graduating with a degree in English and Journalism in 1941, Arnold worked for the New York Daily News until his enlistment in the Army. During World War II, both he and Alfie served with valor. Arnold, who attained the rank of second lieutenant, was awarded the Bronze Arrowhead for his service in the Marshall Islands. Alfie did not make it through: His B-17 was hit by enemy fire over Germany; after helping several enlisted men to safety, he went down with his plane.

When the war ended, Arnold jumped into New York’s literary milieu, teaching and editing, and publishing the fiction he wrote in his spare time. In 1951 he got lucky when he married Bonnie Abraham. The couple worked at the Magazine Management Company, he as editor-in-chief of Lion Books, she as production manager for the young Stan Lee, who went on to Spider-Man comic fame. They were also politically active, going up to Harlem to help register black voters in the late 1940s. (And wouldn’t Lester Rodney, one of the Shrine’s inductees of 2005, delight in that.)

*****

In 1955 Bonnie and Arnold put their 18-month-old daughter Laurel and their beagle puppy into the backseat of their brand new Ford sedan and set out to find a new place to live. Bonnie had found New York City a difficult place to raise a child, and Arnold, who had left Lion Books to write full time, figured he could live and work anywhere. En route on California Highway 1 to visit friends in San Diego, they passed through what Arnold calls “a darling little town … an absolutely charming town, with some sophistication.” To Bonnie it felt like home. Inquiries were made: Was Laguna Beach expensive? “No,” said their friends. “Too many starving artists.” As a newly launched freelance writer, Arnold figured he would fit right in.

Arnold Hano

In Laguna, Arnold and Bonnie discovered a community that engaged their interest in the arts, their love for gardens and old homes, and their passion for grass-roots politics. Early on, the Hanos discovered that the small African-American community in Laguna was not welcome in the city’s three barbershops. Arnold negotiated a change to that. In those days, he wrote during the mornings, with afternoons devoted to ocean swims and body surfing, followed by martinis on the sand. The couple purchased a 1927 Hansel and Gretel-style house in Bluebird Canyon where they live today; the home is on the City’s Historic Register. In 1971 Arnold served as the founding chair of Village Laguna; he was instrumental in establishing height limits along the beachfront. Bonnie is currently the corresponding secretary of the Village Laguna Board of Directors. Since 2003 she has served on the Heritage Committee. Both Hanos still regularly attend City Council meetings. “I love the oldness of Laguna,” says Arnold, “and that we managed to keep it Laguna.” Much of the reason why Laguna Beach does not look like, say, Miami Beach can be attributed to the Hanos’ activism – ask any long-time resident.

Although California proved a good move for the Hanos, Arnold wasn’t nearly as happy when the team he grew up with decided to move to San Francisco in 1958. He got over it. He continues to follow the Giants’ and continues to detest the Dodgers. A Dodger loss, he says, sometimes gives him greater pleasure than a Giant win.

Arnold Hano

In California Arnold was prolific, publishing baseball articles in such venues as Sport magazine, Western novels, and short fiction in Ellery Queen and Alfred Hitchcock magazines, as well as biographies of heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Willie Mays. One morning at breakfast in the early 1950s he and Bonnie heard a radio report. Arnold recalls: “Sen. Joe McCarthy had sent two of his stooges, Roy Cohn and David Schine, over to Europe to investigate U.S. Information Service libraries, to see what kind of ‘communist’ propaganda they were peddling. And they found these ‘communist’ books by Hemingway and Steinbeck, and the news story said they had them burned. I went through the rest of the day kind of feeling that something had been torn out of my stomach. Turned out that was not true. The books were not burned but they were removed.” The report prompted Arnold to write the short story “The Crate at Outpost 1,” about the dangers of not reading. For the crate of the title contains the enemy’s greatest weapon: books. The story has been republished in more than 20 languages. To sum up, Arnold has published more than two dozen books and countless magazine articles. He worked as editor at Pacific Mutual Insurance and taught writing at the University of California at Irvine and the University of Southern California. Along the way, he won such prestigious honors as Magazine Sportswriter of the Year (1963).

Felipe Alou and Arnold Hano (photo courtesy of Jon Leonoudakis)

Another aspect of Arnold’s influence on baseball writing came apparent last year: After he spoke at the NINE Spring Training Conference, in Tempe, Arizona, Felipe Alou showed up to pay his respects. Alou remembered Arnold’s advocacy for early Latino players, a man Alou termed “our hero.” Decades ago, after accepting profile assignments on Orlando Cepeda and Roberto Clemente, Arnold decided to acknowledge what he kept hearing about: the maltreatment of Latino players and misconceptions of their “way of life” by the members of the baseball establishment and the media. “I would speak up about that, and became something of an apologist. When I’d go into the Giant clubhouse to interview someone, Cepeda would come over, take my hand and introduce me around to the Latino players, like Juan Marichal, saying, ‘This is Arnold Hano. He is our friend.’”

Fan to fan, ask Arnold what brings us back to baseball and he quotes a line from the novel Prospect by Bill Littlefield: “’It is a sustaining game.’ Those five words—that’s what holds us,” he says. “I’ve been in thrall to baseball since I was four. So you get hooked. The game has so many things that make it what it is. It’s elegant, it’s spread out the way soccer is but it also has the rigid 90-foot basepaths, and then the outfield goes crazy – it goes any old way. It combines the offense and the defense in one team; you don’t then wait for the new eleven people to come on the field and take on the other guy’s offense.”

So despite the changes to the game, Arnold keeps coming back. With free agency and the movement of franchises and players and management in recent decades, he sees fans’ loyalty fading, though not disappearing. “If only to a logo, we are hooked to that team and it holds us. You walk into a ballpark and the smell of hot dogs grabs you, the look of the green grass.” He cites sportswriter George Vecsey’s point that baseball is the only sport that calls its stadiums a ballpark – “a park,” he emphasizes. “Especially for city kids – baseball is a citified game – for a kid who has traveled by subway or on foot, you walk in and there’s this expanse of green grass and rich brown dirt, and it’s just a feeling of expansiveness.”

*****

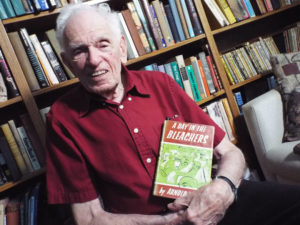

Arnold Hano wih his copy of A Day in the Bleachers (photo courtesy of Jon Leonoudakis)

As a fan, Arnold considers himself blessed by what he terms “momentary spasms of luck.” He won a limerick contest in 1956 and was flown to New York for a World Series game – Don Larsen pitched a perfect game. To celebrate their anniversary in 1962, he brought his long-suffering wife Bonnie, whose heart does not beat to the rhythm of the game, to Dodger Stadium – Sandy Koufax pitched his first no-hitter. Perhaps his greatest luck – and ours – came on September 29, 1954, when the Cleveland Indians met the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds for Game 1 of the World Series. Once settled into the left-center field bleachers, Arnold exchanged insults and observations with rival fans as he scribbled notes and reflections about his seatmates, the play on the field, and the game of baseball in the margins of his program and his folded New York Times. It was his good fortune to be in prime position to witness centerfielder Willie Mays’s running catch of a Vic Wertz line drive – known ever after as “The Catch.” After the Giants won the Series, Arnold typed up his notes and showed them to a friend, wanting to know if they were any good. “Send it out,” he was advised. And thus was launched Arnold’s classic, A Day in the Bleachers, published in 1955.

Arnold still has much to say about his “sustaining game.” He does not approve of the Wild Card, the uneven distribution of teams in both leagues’ divisions, or the American League’s designated hitter rule. “I am so bored out of my skull by the emphasis on the home run,” he says, “and by the fact that we’ve brought the fences in, we’ve lowered the mound, we’ve shrunk the strike zone – now it’s the size of an umpire’s heart.” At which point Arnold likes to jump up to demonstrate an acceptable strike zone. “We’ve juiced up the ball, we’ve juiced up the bat, and we juiced up the players. I think the game’s out of balance as a result…. Pitching intrigues me,” he says, “and I would like to write about that, emphasizing the role of the wonderful rivalry of pitcher versus batter.”

Another story remains to be told, too. Sometimes, when Arnold can’t sleep at night, he thinks about writing. “One of the things I’ve thought of is a short memoir, ‘How Am I Doing, Big Brother?’ Because Alfie was killed when he was 25 years old, and he was my big brother, and I’ve always felt that he was sort of looking over my shoulder, checking me out as I go along, giving me grades, and things like that. When I thought of the title, it gave me the focus that I needed.”

Another story remains to be told, too. Sometimes, when Arnold can’t sleep at night, he thinks about writing. “One of the things I’ve thought of is a short memoir, ‘How Am I Doing, Big Brother?’ Because Alfie was killed when he was 25 years old, and he was my big brother, and I’ve always felt that he was sort of looking over my shoulder, checking me out as I go along, giving me grades, and things like that. When I thought of the title, it gave me the focus that I needed.”

Sixty-one years since it was first published, A Day in the Bleachers is still in print. Arnold is still in play, too, in recent years serving as a panelist at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, a speaker at the NINE Spring Training Conference, and as the subject of Jon Leonoudakis’s fine documentary Hano: A Century in the Bleachers. Arnold is currently nearing completion of a play that will be considered by the Laguna Moulton Playhouse. The play is entitled A Rather Odd Couple and it involves Harry S. Truman and Monica Lewinsky.

Arnold, it’s a pleasure to welcome you to the Shrine of the Eternals Induction ceremony of 2016. How fitting that it comes a neat 90 years after you first learned to cross Edgemont Avenue.

Arnold Hano Shrine of the Eternals induction plaque (photo courtesy of Jesse Saucedo)

Like Arnold Hano, Jean Hastings Ardell is a native New Yorker who now lives and writes in Laguna Beach. She first met Hano at a baseball authors forum at Barnes & Noble in Costa Mesa, California. Ardell is the author of the seminal book Breaking into Baseball: Women and the National Pastime and is co-author of the forthcoming book with lefthanded pitcher and 2003 Shrine of the Eternals inductee Ila Borders, Making My Pitch: A Woman’s Baseball Odyssey.